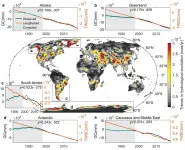

The locations of the North and South poles aren't static, unchanging spots on our planet. The axis Earth spins around--or more specifically the surface that invisible line emerges from--is always moving due to processes scientists don't completely understand. The way water is distributed on Earth's surface is one factor that drives the drift.

Melting glaciers redistributed enough water to cause the direction of polar wander to turn and accelerate eastward during the mid-1990s, according to a new study in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU's journal for high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

"The faster ice melting under global warming was the most likely cause of the directional change of the polar drift in the 1990s," said Shanshan Deng, a researcher at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and an author of the new study.

The Earth spins around an axis kind of like a top, explains Vincent Humphrey, a climate scientist at the University of Zurich who was not involved in this research. If the weight of a top is moved around, the spinning top would start to lean and wobble as its rotational axis changes. The same thing happens to the Earth as weight is shifted from one area to the other.

Researchers have been able to determine the causes of polar drifts starting from 2002 based on data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), a joint mission by NASA and the German Aerospace Center, launched with twin satellites that year and a follow up mission in 2018. The mission gathered information on how mass is distributed around the planet by measuring uneven changes in gravity at different points.

Previous studies released on the GRACE mission data revealed some of the reasons for later changes in direction. For example, research has determined more recent movements of the North Pole away from Canada and toward Russia to be caused by factors like molten iron in the Earth's outer core. Other shifts were caused in part by what's called the terrestrial water storage change, the process by which all the water on land--including frozen water in glaciers and groundwater stored under our continents--is being lost through melting and groundwater pumping.

The authors of the new study believed that this water loss on land contributed to the shifts in the polar drift in the past two decades by changing the way mass is distributed around the world. In particular, they wanted to see if it could also explain changes that occurred in the mid-1990s.

In 1995, the direction of polar drift shifted from southward to eastward. The average speed of drift from 1995 to 2020 also increased about 17 times from the average speed recorded from 1981 to 1995.

Now researchers have found a way to wind modern pole tracking analysis backward in time to learn why this drift occurred. The new research calculates the total land water loss in the 1990s before the GRACE mission started.

"The findings offer a clue for studying past climate-driven polar motion," said Suxia Liu, a hydrologist at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the corresponding author of the new study. "The goal of this project, funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China is to explore the relationship between the water and polar motion."

Water loss and polar drift

Using data on glacier loss and estimations of ground water pumping, Liu and her colleagues calculated how the water stored on land changed. They found that the contributions of water loss from the polar regions is the main driver of polar drift, with contributions from water loss in nonpolar regions. Together, all this water loss explained the eastward change in polar drift.

"I think it brings an interesting piece of evidence to this question," said Humphrey. "It tells you how strong this mass change is--it's so big that it can change the axis of the Earth."

Humphrey said the change to the Earth's axis isn't large enough that it would affect daily life. It could change the length of day we experience, but only by milliseconds.

The faster ice melting couldn't entirely explain the shift, Deng said. While they didn't analyze this specifically, she speculated that the slight gap might be due to activities involving land water storage in non-polar regions, such as unsustainable groundwater pumping for agriculture.

Humphrey said this evidence reveals how much direct human activity can have an impact on changes to the mass of water on land. Their analysis revealed large changes in water mass in areas like California, northern Texas, the region around Beijing and northern India, for example--all areas that have been pumping large amounts of groundwater for agricultural use.

"The ground water contribution is also an important one," Humphrey said. "Here you have a local water management problem that is picked up by this type of analysis."

Liu said the research has larger implications for our understanding of land water storage earlier in the 20th century. Researchers have 176 years of data on polar drift. By using some of the methods highlighted by her and her colleagues, it could be possible to use those changes in direction and speed to estimate how much land water was lost in past years.

INFORMATION:

AGU supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

This research study will be freely available for 30 days. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

"Polar Drift in the 1990s Explained by Terrestrial Water Storage Changes"

Authors:

Shanshan Deng, Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS), Beijing, China.

Suxia Liu, corresponding author, and Xingguo Mo, Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS); College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS); and Sino?Danish College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS), Beijing, China.

Liguang Jiang and Peter Bauer-Gottwein, Department of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, Kgs Lyngby, Denmark.