(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - A new treatment is among the first known to reduce the severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by the flu in animals, according to a new study.

Tests in mice infected with high doses of influenza showed that the treatment could improve lung function in very sick mice and prevent progression of disease in mice that were pre-emptively treated after being exposed to the flu.

The hope is that it may also help humans infected with the flu, and potentially other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) such as SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Specific cells in mice are less able to make key molecules after influenza invades the lungs, reducing their ability to produce a substance called surfactant that enables lungs to expand and contract. The shortage of surfactant is linked to ARDS, an illness so serious that it typically requires mechanical ventilation in an ICU.

Researchers bypassed the blocked process in mice by re-introducing the missing molecules alone or in combination as an injected or oral treatment. The results: normalized blood oxygen levels and reduced inflammation in mouse lungs - effects that could make a person well enough for hospital discharge.

"The most important and impressive thing in this study is the fact that we have benefits even when we treat late in the disease process. If we could develop a drug based on these findings, you could take somebody who's going to have to go on a ventilator and stop that completely," said Ian Davis, professor of veterinary biosciences at The Ohio State University and senior author of the study. "There's nothing out there now that can do this for ARDS that will bring them back to that degree, and certainly not for flu."

ARDS can also result from infections, cancer, trauma and many other ailments. Though this therapy has been tested in the context of the flu, Davis said its reliance on fixing a broken cell function in the host rather than killing the virus suggests it has potential to treat virtually any lung injury.

The study was published online recently in the American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology.

The experimental treatment consists of molecules known as liponucleotides, which are essential for making surfactant in the lungs. Davis analyzed lung cells from flu-infected mice and determined that the pathway to surfactant production was disrupted, with one of the two necessary liponucleotides completely undetectable.

"The thinking before was that the reason there was less surfactant in mice with flu-related ARDS was because cells are dying. This defect is in some ways better - if cells are dying, there's not much you can do, but if there's a problem with the cell's metabolism, maybe you can fix it," Davis said.

And fix it - in mice - he did, developing therapies containing the missing liponucleotide molecule alone or combined with one or two others.

Davis and colleagues inoculated mice with high doses of H1N1 influenza and then treated some mice with liponucleotides once daily for five days and others just a single time five days after exposure. The mice receiving daily treatment were protected from getting seriously ill, and the very sick mice treated on the fifth day, whose severe blood-oxygen loss and lung inflammation had cause ARDS, showed significant improvement.

"Obviously that's what you need in someone with severe influenza - we want to take someone who is already in the ICU and help them get out faster, or head going to the ICU off at the pass," Davis said.

Liponucleotides don't kill the flu virus - which is the point.

"I've always been interested in finding new therapies to treat lung injury," he said. "The problem with anti-viral drugs is you probably need a different drug for every virus. Also, many viruses can quickly mutate to become resistant to these drugs.

"Our approach is to fix the patient. Once the virus has caused the injury - the inflammation - it doesn't really matter if it stays or goes away."

There's still a lot to learn. The agents have a strong anti-inflammatory effect, but don't fully restore the surfactant-production process - and Davis isn't sure why that is. Studies so far have been based on findings in a single type of lung cell, but the scientists haven't confirmed that those cells are the ones responding to the therapy - any number of other cells in the immune system, blood vessels or heart could also play a role.

Despite the unknowns, Davis said that because the missing liponucleotides naturally exist in mammals, including humans, they are considered safe and unlikely to cause side effects, even if they go unused in the body.

The Ohio State Innovation Foundation has filed patents covering the scope of Davis' discoveries, which may also extend to patients suffering from other forms of lung damage that cause inflammation and a drop in blood oxygen levels.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

Co-authors include Lucia Rosas, Lauren Doolittle, Lisa Joseph, Hasan El-Musa and Judy Hickman-Davis of Ohio State's College of Veterinary Medicine; Michael Novotny from the Cleveland Clinic; and Duncan Hite from the University of Cincinnati.

Contact: Ian Davis, Davis.2448@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

An international collaboration of astronomers led by a researcher from the Astrobiology Center and Queen's University Belfast, and including researchers from Trinity College Dublin, has detected a new chemical signature in the atmosphere of an extrasolar planet (a planet that orbits a star other than our Sun).

The hydroxyl radical (OH) was found on the dayside of the exoplanet WASP-33b. This planet is a so-called 'ultra-hot Jupiter', a gas-giant planet orbiting its host star much closer than Mercury orbits the Sun and therefore reaching atmospheric temperatures of more than 2,500° C (hot enough to melt most metals).

The lead researcher based at the Astrobiology Center and Queen's University Belfast, ...

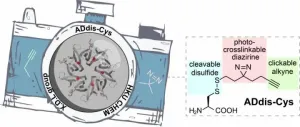

A research group led by Professor Xiang David LI from the Research Division for Chemistry and the Department of Chemistry, The University of Hong Kong, has developed a novel chemical tool for elucidating protein interaction networks in cells. This tool not only facilitates the identification of a protein's interacting partners in the complex cellular context, but also simultaneously allows the 'visualisation' of these protein-protein interactions. The findings were recently published in the prestigious scientific journal Molecular Cell.

In the human body, proteins interact with each other to cooperatively regulate essentially every biological process ranging from gene expression and signal transduction, to immune response. As a result, dysregulated ...

The researchers in this study reached this conclusion by drawing on network modelling research and mapped the job landscapes in cities across the United States during economic crises.

Knowing and understanding which factors contribute to the health of job markets is interesting as it can help promote faster recovery after a crisis, such as a major economic recession or the current COVID pandemic. Traditional studies perceive the worker as someone linked to a specific job in a sector. However, in the real-world professionals often end up working in other sectors that require similar skills. In this sense, researchers consider job markets as being something similar to ecosystems, where organisms are linked in a complex network of interactions.

In this context, an effective job market depends ...

During the Bronze Age, Mesopotamia was witness to several climate crises. In the long run, these crises prompted the development of stable forms of State and therefore elicited cooperation between political elites and non-elites. This is the main finding of a study published in the journal PNAS and authored by two scholars from the University of Bologna (Italy) and Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (Germany).

This study investigated the impact of climate shocks in Mesopotamia between 3100 and 1750 bC. The two scholars looked at these issues through the lenses of economics and adopted a game-theory approach. They applied this approach ...

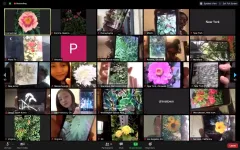

A new paper on college science classes taught remotely points to teaching methods that enhance student communication and collaboration, offering a framework for enriching online instruction as the coronavirus pandemic continues to limit in-person courses.

"These varied exercises allow students to engage, team up, get outside, do important lab work, and carry out group investigations and presentations under extraordinarily challenging circumstances--and from all over the world," explains Erin Morrison, a professor in Liberal Studies at New York University and the lead author of the paper, which appears in the Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education. "The active-learning toolbox can be effectively used from ...

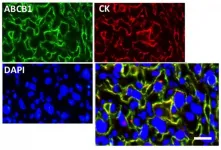

The placenta forms the interface between the maternal and foetal circulatory systems. As well as ensuring essential nutrients, endocrine and immunological signals get through to the foetus to support its development and growth, the placenta must also protect it from the accumulation of potentially toxic compounds. A study from Cécile Demarez, Mariana Astiz and colleagues at the University of Lübeck in Germany now reveals that the activity of a crucial placental gatekeeper in mice is regulated by the circadian clock, changing during the day-night cycle. The study, which has implications for the timing of maternal drug regimens, is published in the journal Development.

The circadian clock translates time-of-day information into physiological signals through rhythmic regulation ...

The combined effect of rapid ocean warming and the practice of targeting big fish is affecting the viability of wild populations and global fish stock says new research by the University of Melbourne and the University of Tasmania.

Unlike earlier studies that traditionally considered fishing and climate in isolation, the research found that ocean warming and fishing combined to impact on fish recruitment, and that this took four generations to manifest.

"We found a strong decline in recruitment (the process of getting new young fish into a population) in all populations that had been exposed to warming, and this effect was highest where all the largest individuals ...

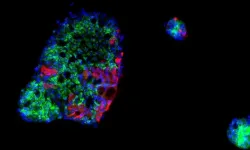

In an effort to determine the potential for COVID-19 to begin in a person's gut, and to better understand how human cells respond to SARS-CoV-2, the scientists used human intestinal cells to create organoids - 3D tissue cultures derived from human cells, which mimic the tissue or organ from which the cells originate. Their conclusions, published in the journal Molecular Systems Biology, indicate the potential for infection to be harboured in a host's intestines and reveal intricacies in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

"Previous research had shown that SARS-CoV-2 can infect the gut," says Theodore Alexandrov, who leads one of the two EMBL groups involved. "However, it remained unclear how intestinal cells mount their immune response to the infection."

In fact, ...

The building of new homes continues in flood-prone parts of England and Wales, and losses from flooding remain high. A new study, which looked at a recent decade of house building, concluded that a disproportionate number of homes built in struggling or declining neighbourhoods will end up in high flood-risk areas due to climate change.

The study, by Viktor Rözer and Swenja Surminski from the Grantham Research Institute, used property-level data for new homes and information on the socio-economic development of neighbourhoods to analyse spatial clusters ...

Ship movements on the world's oceans dropped in the first half of 2020 as Covid-19 restrictions came into force, a new study shows.

Researchers used a satellite vessel-tracking system to compare ship and boat traffic in January to June 2020 with the same period in 2019.

The study, led by the University of Exeter (UK) and involving the Balearic Islands Coastal Observing and Forecasting System and the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies (both in Spain), found decreased movements in the waters off more than 70 per cent of countries.

Global ...