(Press-News.org) University of South Australia researchers have drawn inspiration from a 300-million-year-old superior flying machine - the dragonfly - to show why future flapping wing drones will probably resemble the insect in shape, wings and gearing.

A team of PhD students led by UniSA Professor of Sensor Systems, Javaan Chahl, spent part of the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown designing and testing key parts of a dragonfly-inspired drone that might match the insect's extraordinary skills in hovering, cruising and aerobatics.

The UniSA students worked remotely on the project, solving mathematical formulas at home on whiteboards, digitising stereo photographs of insect wings into 3D models, and using spare rooms as rapid prototyping workshops to test parts of the flapping wing drone.

Their findings have been published in the journal Drones.

Describing the dragonfly as the "apex insect flyer," Prof Chahl says numerous engineering lessons can be learned from its mastery in the air.

"Dragonflies are supremely efficient in all areas of flying. They need to be. After emerging from under water until their death (up to six months), male dragonflies are involved in perpetual, dangerous combat against male rivals. Mating requires an aerial pursuit of females and they are constantly avoiding predators. Their flying abilities have evolved over millions of years to ensure they survive," Prof Chahl says.

"They can turn quickly at high speeds and take off while carrying more than three times their own body weight. They are also one of nature's most effective predators, targeting, chasing and capturing their prey with a 95 per cent success rate."

The use of drones has exploded in recent years - for security, military, delivery, law enforcement, filming, and more recently health screening purposes - but in comparison to the dragonfly and other flying insects they are crude and guzzle energy.

The UniSA team modelled the dragonfly's unique body shape and aerodynamic properties to understand why they remain the ultimate flying machine.

Because intact dragonflies are notoriously difficult to capture, the researchers developed an optical technique to photograph the wing geometry of 75 different dragonfly (Odonata) species from glass display cases in museum collections.

In a world first experiment, they reconstructed 3D images of the wings, comparing differences between the species.

"Dragonfly wings are long, light and rigid with a high lift-to-drag ratio which gives them superior aerodynamic performance.

"Their long abdomen, which makes up about 35 per cent of their body weight, has also evolved to serve many purposes. It houses the digestive tract, is involved in reproduction, and it helps with balance, stability and manoeuvrability. The abdomen plays a crucial role in their flying ability."

The researchers believe a dragonfly lookalike drone could do many jobs, including collecting and delivering awkward, unbalanced loads, safely operating near people, exploring delicate natural environments and executing long surveillance missions.

INFORMATION:

Notes for editors

Images and multimedia are available for media via this link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1B2Ya93rQ1g-lL9IbEUqSUvgmq9Levg6j?usp=sharing

For captions/explanations re the photographs and video, please email candy.gibson@unisa.edu.au

"Biomimetic drones inspired by dragonflies will require a systems-based approach and insights from biology" is published in the latest edition of Drones. For a copy of the paper please email candy.gibson@unisa.edu.au

Prof Javaan Chahl has a joint appointment with the Defence Science and Technology Group. The other researchers involved in the project included UniSA PhD students Nasim Chitsaz, Blake McIvor and Titilayo Ogunwa; UniSA engineer Timothy McIntyre; Jia-Ming Kok (DST Group) and Dr Ermira Abdullah (University Putra Malaysia)

The current loss of biological diversity is unprecedented and species extinctions exceed the estimated background rate many times over. Coinciding with increasing human domination and alteration of the natural world, this loss in abundance and diversity is especially pronounced with - but not limited to - fauna in the tropics. A new publication from scientists at the Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS) in Sweden and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) in Germany now explores the links between defaunation of tropical forests and the United ...

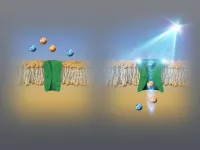

Several organisms possess "ion channels" (gateways that selectively allow charged particles called ions to enter the cells and are integral for cell function) called "channelrhodopsins," that can be switched on and off with the help of light. Different channelrhodopsins respond to different wavelengths in the light spectrum. These channels can be expressed in foreign organisms (animals even in human) by means of genetic engineering, which in turn finds applications in optogenetics, or the application of light to modulate cellular and gene functions. So far, the shortest wavelength that a channelrhodopsin ...

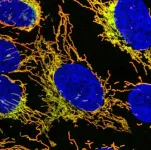

Monash University researchers have uncovered for the first time the reason mutations in a particular gene lead to mitochondrial disease.

The finding, published in PNAS journal and led by Professor Mike Ryan from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute, shows that a gene responsible for causing loss of vision and hearing, TMEM126A, makes a protein that helps build an important energy generator in mitochondria. So, if this gene is defective, it reduces mitochondrial function and impares energy production, uncovering why mutations lead to the disease.

Mitochondria are critical structures within ...

Portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH) is a form of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). PoPH occurs in approximately 15% of patients with PAH, and is reportedly found in 2-6% of patients with portal hypertension and 1-2% of patients with liver cirrhosis according to studies from Europe and America. However, the real-world data on PoPH in Japan are largely unknown, with many questions on the condition's etiology and prevalence.

Led by doctorate student Shun-ichi Wakabayashi of Shinshu University, the goal of this investigation is to clarify the actual state of PoPH among patients with chronic liver disease by screening all such patients treated at Shinshu University Hospital.

Although there is considerable uncertainty on the impact of PoPH, it is known that ...

Examples of complex systems exist everywhere. Neuron connections and protein-protein interactions are two systems of this type found in organisms, but complex systems also exist in cities, economic models, and even in social networks. The common denominator is that they are made up of many interrelated elements which can be represented and studied as a network.

For more than a decade, scientists have been studying the possibility of finding more than one type of structural organization within a single network, and this is the subject of the doctoral thesis defended by María José Palazzi, as part of the UOC's doctoral programme in Network and Information Technologies. ...

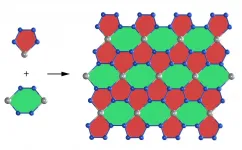

An international team with researchers from the University of Bayreuth has succeeded for the first time in discovering a previously unknown two-dimensional material by using modern high-pressure technology. The new material, beryllonitrene, consists of regularly arranged nitrogen and beryllium atoms. It has an unusual electronic lattice structure that shows great potential for applications in quantum technology. Its synthesis required a compression pressure that is about one million times higher than the pressure of the Earth's atmosphere. The scientists have presented their discovery in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Since the discovery of graphene, which is made of carbon atoms, interest in two-dimensional ...

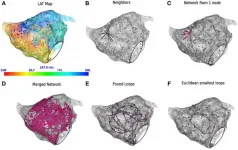

Researchers from Belgium, the Netherlands, Russia, and Italy have developed a breakthrough method for quickly, accurately, and reliably diagnosing cardiac arrhythmias. They called it Directed graph mapping (DGM). The technology principles are published in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

One of the members of the research team is Alexander Panfilov, leading specialist of the laboratory of computational biology and medicine at Ural Federal University (Russia), head of the biophysics group at the University of Ghent (Belgium), professor at the Department of Cardiology at Leiden University (Netherlands). The research was led ...

Tightening the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) in line with the EU Green Deal would dramatically speed up the decarbonization of Europe's power sector - and likely cause a demise of the coal industry. In a new study a team of researchers from Potsdam, Germany has quantified the substantial shifts Europe's electricity system is about to undergo when the newly decided EU climate target gets implemented. Higher carbon prices, the authors show, are not only an inevitable step to cut emissions - they will also lead much faster to an inexpensive electricity system powered by renewable energies.

"Once the EU translates their recently adjusted target of cutting emissions by at least 55% in 2030 in comparison to 1990 into tighter EU ETS caps, the electricity sector will see fundamental changes ...

The neutron reflexometry method has given scientists an atomic-level insight into the behaviour of Bcl-2, a protein that promotes cancerous cell growth. The new study was carried out by Umeå chemists in collaboration with the research facilities ESS and ISIS and is published in Nature Communications Biology.

Elevated function of the cell-protecting membrane protein Bcl-2 can promote cancer and cause resistance to cancer treatment. Developing an understanding of the way it does this could inform the development of anti-cancer drugs.

It may seem counter-intuitive, ...

Western Australia's wheatbelt is a biodiversity desert, but the remaining wildlife - surviving in 'wheatbelt oases' - may offer insights for better conservation everywhere, according to researchers.

University of Queensland researcher Dr Graham Fulton and local John Lawson have been reviewing the biodiversity in the woodland oasis of Dryandra, in WA's south west.

"It's hard to witness the devastating loss of wilderness in Western Australia's wheatbelt," Dr Fulton said.

"Ninety-seven per cent of the best native vegetation has been taken - around 14 million hectares - it's an area greater in size ...