(Press-News.org) Researchers funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) at the University of Oxford have uncovered a clue that may help to explain why the earliest evidence of complex multicellular animal life appears around 550 million years ago, when atmospheric oxygen levels on the planet rose sharply from 3% to their modern day level of 21%.

The team, led by Professor Chris Schofield, has found that humans share a method of sensing oxygen with the world's simplest known living animal - Trichoplax adhaerens - suggesting the method has been around since the first animals emerged around 550 million years ago.

This discovery, published today (17 December) in the January 2011 edition of EMBO Reports, throws light on how humans sense oxygen and how oxygen levels drove the very earliest stages of animal evolution.

Professor Schofield said "It's absolutely necessary for any multicellular organism to have a sufficient supply of oxygen to almost every cell and so the atmospheric rise in oxygen made it possible for multicellular organisms to exist.

"But there was still a very different physiological challenge for these organisms than for the more evolutionarily ancient single-celled organisms such as bacteria. Being multicelluar means oxygen has to get to cells not on the surface of the organism. We think this is what drove the ancesters of Trichoplax adhaerens to develop a system to sense a lack of oxygen in any cell and then do something about it."

The oxygen sensing process enables animals to survive better at low oxygen levels, or 'hypoxia'. In humans this system responds to hypoxia, such as is caused by high altitudes or physical exertion, and is very important for the prevention of stroke and heart attacks as well as some types of cancer.

Trichoplax adhaerens is a tiny seawater organism that lacks any organs and has only five types of cells, giving it the appearance of an amoeba. By analysing how Trichoplax reacts to a lack of oxygen, Oxford researcher Dr Christoph Loenarz found that it uses the same mechanism as humans - in fact, when the key enzyme from Trichoplax was put it in a human cell, it worked just as well as the human enzyme usually would.

They also looked at the genomes of several other species and found that this mechanism is present in multi-cellular animals, but not in the single-celled organisms that were the precursors of animals, suggesting that the mechanism evolved at the same time as the earliest multicellular animals

Defects in the most important human oxygen sensing enzyme can cause polycythemia

- an increase in red blood cells. The work published today could also open up new approaches to develop therapies for this disorder.

Professor Douglas Kell, Chief Executive, BBSRC said "Understanding how animals - and ultimately humans - evolved is essential to our ability to pick apart the workings of our cells. Knowledge of normal biological processes underpins new developments that can improve quality of life for everyone. The more skilful we become in studying the evolution of some of our most essential cell biology, the better our chances of ensuring long term health and well being to match the increase in average lifespan in the UK and beyond."

###

CONTACT

Professor Chris Schofield, Tel: +44 1865 275625, email:

christopher.schofield@chem.ox.ac.uk

BBSRC External Relations

Nancy Mendoza, Tel: 01793 413355, email: nancy.mendoza@bbsrc.ac.uk

Mike Davies, Tel: 01793 442042, email: mike.davies@bbsrc.ac.uk

Matt Goode, Tel: 01793 413299, email: matt.goode@bbsrc.ac.uk

NOTES TO EDITORS

IMAGES AVAILABLE -http://workspace.meltwaterdrive.com/share/D15321EA02

Please note word document in this folder with caption and copyright information

* A report entitled "The hypoxia-inducible transcription factor pathway regulates oxygen sensing in the simplest animal, Trichoplax adhaerens" will be published in the January edition of EMBO Reports on 17 December 2010.

* The team was led by Professor Chris Schofield of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry, with Professor Peter Ratcliffe from Oxford's Centre for Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Professor Peter Holland from Oxford's Zoology Department and, at the University of Hannover in Germany, Professor Bernd Schierwater.

* The article is available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2010.170,

together with an introduction that highlights key aspects of the research, at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2010.192

About BBSRC

BBSRC is the UK funding agency for research in the life sciences and the largest single public funder of agriculture and food-related research. Sponsored by Government, in 2010/11 BBSRC is investing around £470 million in a wide range of research that makes a significant contribution to the quality of life in the UK and beyond and supports a number of important industrial stakeholders, including the agriculture, food, chemical, healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

BBSRC provides institute strategic research grants to the following:

The Babraham Institute, Institute for Animal Health, Institute for Biological, Environmental and Rural Studies (Aberystwyth University), Institute of Food Research, John Innes Centre, The Genome Analysis Centre, The Roslin Institute (University of Edinburgh) and Rothamsted Research. The Institutes conduct long- term, mission-oriented research using specialist facilities. They have strong interactions with industry, Government departments and other end-users of their research.

For more information see: http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk

Danish sleep researchers at the University of Copenhagen and the Danish Institute for Health Services Research have examined the socio-economic consequences of the sleep disorder hypersomnia in one of the largest studies of its kind. The sleep disorder has far-reaching consequences for both the individual and society as a whole.

Hypersomnia is characterised by excessive tiredness during the day. Patients who suffer from the disorder are extremely sleepy and need to take a nap several times a day. This can occur both at work, during a meal, in the middle of a conversation ...

VIDEO:

In this animated illustration, an electron (black ball) flies across a lattice of magnetic vortices. The forces transferred in the process allow the magnetic structures to be controlled with relatively...

Click here for more information.

One of the requirements to keep trends in computer technology on track – to be ever faster, smaller, and more energy-efficient – is faster writing and processing of data. In the Dec. 17 issue of the journal Science, physicists ...

Cancer treatment with ion beams developed at GSI is characterized by an excellent cure rate and only minor side effects. The therapy has been routinely in use for a little over one year. The effectiveness of the ion beams not only depends on the tumor type, but also on the genetic disposition and the personal circumstances of the individual patient. For the first time, scientists at GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung have irradiated samples of vital human tumor tissue in the scope of their systematical and fundamental research. Their long-term goal is to enhance ...

Plants that "lose the battle" during competitiveness for light because they are shaded by larger neighbours, counteract. They adapt by rapid shoot elongation and stretch their leaves towards the sun. The molecular basis of this so-called shade avoidance syndrome had been unclarified to date. Research scientists from the Utrecht University in the Netherlands and the Ruhr University in Bochum have now been able to unravel a regulation pathway. A specific transport protein (PIN3) enables the accumulation of the plant hormone auxin, which plays an important role during this ...

"I have ready!" With this sentence the FC Bayern Munich coach Giovanni Trapattoni finished a furious rant about his team's performance in 1998. And "Mr Angelo" in a coffee advert points out to his neighbour with a mischievous smile: "I don't have a car at all". In both cases the Italians are unmistakeably recognizable and so the exuberant temperament of the first and the charming way of the second are seemingly "typically Italian".

The accent someone talks in plays a crucial role in the way we judge this person, psychologists of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena ...

VIDEO:

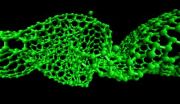

Compression causes nanotubes to buckle and twist and eventually to lose atoms from their lattice-like structure.

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A pipefitter knows how to make an exact cut on a metal rod. But it's far harder to imagine getting a precise cut on a carbon nanotube, with a diameter 1/50,000th the thickness of a human hair.

In a paper published this month in the British journal Proceedings of the Royal Society ...

MANHATTAN, KAN. -- Two Kansas State University researchers focusing on rice genetics are providing a better understanding of how pathogens take over a plant's nutrients.

Their research provides insight into ways of reducing crop losses or developing new avenues for medicinal research.

Frank White, professor of plant pathology, and Ginny Antony, postdoctoral fellow in plant pathology, are co-authors, in partnership with researchers at three other institutions, of an article in a recent issue of the journal Nature. The article, "Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange ...

Like a fence or barricade intended to stop unwanted intruders, the skin serves as a barrier protecting the body from the hundreds of allergens, irritants, pollutants and microbes people come in contact with every day. In patients with eczema, or atopic dermatitis, the most common inflammatory human skin disease, the skin barrier is leaky, allowing intruders – pollen, mold, pet dander, dust mites and others – to be sensed by the skin and subsequently wreak havoc on the immune system.

While the upper-most layer of the skin – the stratum corneum – has been pinned as the ...

50 million years ago, mountains began popping up in southern British Columbia. Over the next 22 million years, a wave of mountain building swept (geologically speaking) down western North America as far south as Mexico and as far east as Nebraska, according to Stanford geochemists. Their findings help put to rest the idea that the mountains mostly developed from a vast, Tibet-like plateau that rose up across most of the western U.S. roughly simultaneously and then subsequently collapsed and eroded into what we see today.

The data providing the insight into the mountains ...

Computer games and simulations are worthy of future investment and investigation as a way to improve science learning, says LEARNING SCIENCE: COMPUTER GAMES, SIMULATIONS, AND EDUCATION, a new report from the National Research Council. The study committee found promising evidence that simulations can advance conceptual understanding of science, as well as moderate evidence that they can motivate students for science learning. Research on the effectiveness of games designed for science learning is emerging, but remains inconclusive, the report says.###

The report is available ...