(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - Tiny molecules called nanobodies, which can be designed to mimic antibody structures and functions, may be the key to blocking a tick-borne bacterial infection that remains out of reach of almost all antibiotics, new research suggests.

The infection is called human monocytic ehrlichiosis, and is one of the most prevalent and potentially life-threatening tick-borne diseases in the United States. The disease initially causes flu-like symptoms common to many illnesses, and in rare cases can be fatal if left untreated.

Most antibiotics can't build up in high enough concentrations to kill the infection-causing bacteria, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, because the microbes live in and multiply inside human immune cells. Commonly known bacterial pathogens like Streptococcus and E. coli do their infectious damage outside of hosts' cells.

Ohio State University researchers created nanobodies intended to target a protein that makes E. chaffeensis bacteria particularly infectious. A series of experiments in cell cultures and mice showed that one specific nanobody they created in the lab could inhibit infection by blocking three ways the protein enables the bacteria to hijack immune cells.

"If multiple mechanisms are blocked, that's better than just stopping one function, and it gives us more confidence that these nanobodies will really work," said study lead author Yasuko Rikihisa, professor of veterinary biosciences at Ohio State.

The study provided support for the feasibility of nanobody-based ehrlichiosis treatment, but much more research is needed before a treatment would be available for humans. There is a certain urgency to coming up with an alternative to the antibiotic doxycycline, the only treatment available. The broad-spectrum antibiotic is unsafe for pregnant women and children, and it can cause severe side effects.

"With only a single antibiotic available as a treatment for this infection, if antibiotic resistance were to develop in these bacteria, there is no treatment left. It's very scary," Rikihisa said.

The research is published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The bacteria that cause ehrlichiosis are part of a family called obligatory intracellular bacteria. E. chaffeensis not only requires internal access to a cell to live, but also blocks host cells' ability to program their own death with a function called apoptosis - which would kill the bacteria.

"Infected cells normally would commit suicide by apoptosis to kill the bacteria inside. But these bacteria block apoptosis and keep the cell alive so they can multiply hundreds of times very rapidly and then kill the host cell," Rikihisa said.

A longtime specialist in the Rickettsiales family of bacteria to which E. chaffeensis belongs, Rikihisa developed the precise culture conditions that enabled growing these bacteria in the lab in the 1980s, which led to her dozens of discoveries explaining how they work. Among those findings was identification of proteins that help E. chaffeensis block immune cells' programmed cell death.

The researchers synthesized one of those proteins, called Etf-1, to make a vaccine-style agent that they used to immunize a llama with the help of Jeffrey Lakritz, professor of veterinary preventive medicine at Ohio State. Camels, llamas and alpacas are known to produce single-chain antibodies that include a large antigen binding site on the tip.

The team snipped apart segments of that binding site to create a library of nanobodies with potential to function as antibodies that recognize and attach to the Etf-1 protein and stop E. chaffeensis infection.

"They function similarly to our own antibodies, but they're tiny, tiny nano-antibodies," Rikihisa said. "Because they are small, they get into nooks and crannies and recognize antigens much more effectively.

"Big antibodies cannot fit inside a cell. And we don't need to rely on nanobodies to block extracellular bacteria because they are outside and accessible to ordinary antibodies binding to them."

After screening the candidates for their effectiveness, the researchers landed on a single nanobody that attached to Etf-1 in cell cultures and inhibited three of its functions. By making the nanobodies in the fluid inside E. coli cells, Rikihisa said her lab could produce them at an industrial scale if needed - packing millions of them into a small drop.

She collaborated with co-author Dehua Pei, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Ohio State, to combine the tiny molecules with a cell-penetrating peptide that enabled the nanobodies to be safely delivered to mouse cells.

Mice with compromised immune systems were inoculated with a highly virulent strain of E. chaffeensis and given intracellular nanobody treatments one and two days after infection. Compared to mice that received control treatments, mice that received the most effective nanobody showed significantly lower levels of bacteria two weeks after infection.

With this study providing the proof of principle that nanobodies can inhibit E. chaffeensis infection by targeting a single protein, Rikihisa said there are multiple additional targets that could provide even more protection with nanobodies delivered alone or in combination. She also said the concept is broadly applicable to other intracellular diseases.

"Cancers and neurodegenerative diseases work in our cells, so if we want to block an abnormal process or abnormal molecule, this approach may work," she said.

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Additional co-authors, all from Ohio State, include Wenqing Zhang, Mingqun Lin, Qi Yan, Khemraj Budachetri, Libo Hou, Ashweta Sahni, Hongyan Liu and Nien-Ching Han.

Contact: Yasuko Rikihisa, Rikihisa.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

ATLANTA--Processed diets, which are low in fiber, may initially reduce the incidence of foodborne infectious diseases such as E. coli infections, but might also increase the incidence of diseases characterized by low-grade chronic infection and inflammation such as diabetes, according to researchers in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University.

This study used mice to investigate how changing from a grain-based diet to a highly processed, high-fat Western style diet impacts infection with the pathogen Citrobacter rodentium, which resembles Escherichia coli (E. coli) infections in humans. The findings are published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Gut microbiota, the microorganisms living in the intestine, provide a number of benefits, ...

The scientific community is focusing its research into the multiple applications of Hydrogels, polymeric materials which contains a large amount of water, that have the potential to reproduce the features of biological tissues. This aspect is particularly significant in the field of regenerative medicine, which since a long time has already recognised and been using the characteristics of these materials. In order to be used effectively to replace organic tissues, hydrogels must meet two essential requirements: possessing great geometric complexity and, after suffering of a damage, being ...

Researchers at the University of Bath investigating how virtual reality (VR) can help improve balance believe this technology could be a valuable tool in the prevention of falls.

As people grow older, losing balance and falling becomes more common, which increases the risk of injury and affects the person's independence.

Falls are the leading cause of non-fatal injuries in over 65-yearolds and account for over 4 million bed days per year in England alone, at an estimated cost of £2 billion.

Humans use three ways of keeping their balance: vision, proprioceptive (physical feedback from muscles and joints) and vestibular system (feedback from semi-circular canals in the ear). Of these, vision is the most important.

Traditional ways of assessing balance ...

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- New Army-funded synthetic biology research manipulated micro-compartments in cells, potentially enabling bio-manufacturing advances for medicine, protective equipment and engineering applications.

Bad bacteria can survive in extremely hostile environments -- including inside the highly acidic human stomach--thanks to their ability to sequester toxins into tiny compartments.

In a new study, published in ACS Central Science, Northwestern University researchers controlled protein assembly and built these micro-compartments into different shapes ...

Boston - This year, more than 60,000 adults in the United States will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and, statistically, as few as 10 percent will survive five years after diagnosis, according to the American Cancer Society. Because pancreatic cancer is hidden deep within the body and often symptomless, it's frequently diagnosed after the disease has progressed too far for surgical intervention and/or has spread throughout the body. Research indicates that earlier detection of pancreatic tumors could quadruple survival rates; however, no validated and reliable tests for early detection of pancreatic cancer currently exist.

Now, researchers at the Cancer Research Institute at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) have successfully created ...

Every day, the sun ejects large amounts of a hot particle soup known as plasma toward Earth where it can disrupt telecommunications satellites and damage electrical grids. Now, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University's Department of Astrophysical Sciences have made a discovery that could lead to better predictions of this space weather and help safeguard sensitive infrastructure.

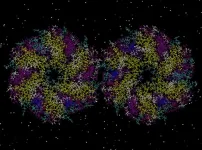

The discovery comes from a new computer model that predicts the behavior of the plasma in the region above the surface of the sun known as the solar corona. The model was originally inspired by a similar model that describes the behavior of the plasma that fuels fusion reactions in doughnut-shaped fusion facilities known ...

Although plants may look fairly inactive to casual observers, research into plant biology has shown that plants can send each other signals concerning threats in their local environments. These signals take the form of airborne chemicals, called volatile organic compounds (VOCs), released from one plant and detected by another, and plant biologists have found that a diverse class of chemicals called terpenoids play a major role as airborne danger signals.

Past studies have shown that soybean and lima bean plants both release terpenoid signals that activate defense-related genes in neighboring plants of the same species, and this chemically induced gene activation can help the plants protect themselves from ...

It's well established that infectious disease is the greatest threat to the endangered chimpanzees made famous by the field studies of Jane Goodall at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Now, new research led by scientists at Emory University shows that nearly half of the fecal samples from wild chimpanzees contain bacteria that is resistant to a major class of antibiotics commonly used by people in the vicinity of the park.

The journal Pathogens published the findings.

"Our results suggest that antibiotic-resistant bacteria is actually spreading from people to non-human primates by making its way into the local watershed," says Thomas Gillespie, senior author ...

Rhinelander, Wis., April 28, 2021-- A research team from the USDA Forest Service and the University of Missouri has developed a new contaminant prioritization tool that has the potential to increase the effectiveness of environmental approaches to landfill clean-up.

Phytoremediation - an environmental approach in which trees and other plants are used to control leachate and treat polluted water and soil - hinges on matching the capability of different tree species with the types of contaminants present in soil and water. Identifying the worst contaminants ...

LAWRENCE -- College students across the country struggle with a vicious cycle: Test anxiety triggers poor sleep, which in turn reduces performance on the tests that caused the anxiety in the first place.

New research from the University of Kansas just published in the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine is shedding light on this biopsychosocial process that can lead to poor grades, withdrawal from classes and even students who drop out. Indeed, about 40% of freshman don't return to their universities for a second year in the United States.

"We were interested in finding out what predicted students' performance in statistics classes ...