(Press-News.org) Every day, the sun ejects large amounts of a hot particle soup known as plasma toward Earth where it can disrupt telecommunications satellites and damage electrical grids. Now, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University's Department of Astrophysical Sciences have made a discovery that could lead to better predictions of this space weather and help safeguard sensitive infrastructure.

The discovery comes from a new computer model that predicts the behavior of the plasma in the region above the surface of the sun known as the solar corona. The model was originally inspired by a similar model that describes the behavior of the plasma that fuels fusion reactions in doughnut-shaped fusion facilities known as tokamaks.

Fusion, the power that drives the sun and stars, combines light elements in the form of plasma -- the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei -- that generates massive amounts of energy. Scientists are seeking to replicate fusion on Earth for a virtually inexhaustible supply of power to generate electricity.

The Princeton scientists made their findings while studying roped-together magnetic fields that loop into and out of the sun. Under certain conditions, the loops can cause hot particles to erupt from the sun's surface in enormous burps known as coronal mass ejections. Those particles can eventually hit the magnetic field surrounding Earth and cause auroras, as well as interfere with electrical and communications systems.

"We need to understand the causes of these eruptions to predict space weather," said Andrew Alt, a graduate student in the Princeton Program in Plasma Physics at PPPL and lead author of the paper reporting the results in the Astrophysical Journal.

The model relies on a new mathematical method that incorporates a novel insight that Alt and collaborators discovered into what causes the instability. The scientists found that a type of jiggling known as the "torus instability" could cause roped magnetic fields to untether from the sun's surface, triggering a flood of plasma.

The torus instability loosens some of the forces keeping the ropes tied down. Once those forces weaken, another force causes the ropes to expand and lift further off the solar surface. "Our model's ability to accurately predict the behavior of magnetic ropes indicates that our method could ultimately be used to improve space weather prediction," Alt said.

The scientists have also developed a way to more accurately translate laboratory results to conditions on the sun. Past models have relied on assumptions that made calculations easier but did not always simulate plasma precisely. The new technique relies only on raw data. "The assumptions built into previous models remove important physical effects that we want to consider," Alt said. "Without these assumptions, we can make more accurate predictions."

To conduct their research, the scientists created magnetic flux ropes inside PPPL's Magnetic Reconnection Experiment (MRX), a barrel-shaped machine designed to study the coming together and explosive breaking apart of the magnetic field lines in plasma. But flux ropes created in the lab behave differently than ropes on the sun, since, for example, the flux ropes in the lab have to be contained by a metal vessel.

The researchers made alterations to their mathematical tools to account for these differences, ensuring that results from MRX could be translated to the sun. "There are conditions on the sun that we cannot mimic in the laboratory," said PPPL physicist Hantao Ji, a Princeton University professor who advises Alt and contributed to the research. "So, we adjust our equations to account for the absence or presence of certain physical properties. We have to make sure our research compares apples to apples so our results will be accurate."

Discovery of the jiggling plasma behavior could also lead to more efficient generation of fusion-powered electricity. Magnetic reconnection and related plasma behavior occur in tokamaks as well as on the sun, so any insight into these processes could help scientists control them in the future.

Support for this research came from the DOE, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the German Research Foundation. Research partners include Princeton University, Sandia National Laboratories, the University of Potsdam, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

PPPL, on Princeton University's Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas -- ultra-hot, charged gases -- and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, which is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science

INFORMATION:

Although plants may look fairly inactive to casual observers, research into plant biology has shown that plants can send each other signals concerning threats in their local environments. These signals take the form of airborne chemicals, called volatile organic compounds (VOCs), released from one plant and detected by another, and plant biologists have found that a diverse class of chemicals called terpenoids play a major role as airborne danger signals.

Past studies have shown that soybean and lima bean plants both release terpenoid signals that activate defense-related genes in neighboring plants of the same species, and this chemically induced gene activation can help the plants protect themselves from ...

It's well established that infectious disease is the greatest threat to the endangered chimpanzees made famous by the field studies of Jane Goodall at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Now, new research led by scientists at Emory University shows that nearly half of the fecal samples from wild chimpanzees contain bacteria that is resistant to a major class of antibiotics commonly used by people in the vicinity of the park.

The journal Pathogens published the findings.

"Our results suggest that antibiotic-resistant bacteria is actually spreading from people to non-human primates by making its way into the local watershed," says Thomas Gillespie, senior author ...

Rhinelander, Wis., April 28, 2021-- A research team from the USDA Forest Service and the University of Missouri has developed a new contaminant prioritization tool that has the potential to increase the effectiveness of environmental approaches to landfill clean-up.

Phytoremediation - an environmental approach in which trees and other plants are used to control leachate and treat polluted water and soil - hinges on matching the capability of different tree species with the types of contaminants present in soil and water. Identifying the worst contaminants ...

LAWRENCE -- College students across the country struggle with a vicious cycle: Test anxiety triggers poor sleep, which in turn reduces performance on the tests that caused the anxiety in the first place.

New research from the University of Kansas just published in the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine is shedding light on this biopsychosocial process that can lead to poor grades, withdrawal from classes and even students who drop out. Indeed, about 40% of freshman don't return to their universities for a second year in the United States.

"We were interested in finding out what predicted students' performance in statistics classes ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (04/28/2021) -- In a recent discovery by University of Minnesota Medical School, researchers uncovered a new way to potentially target and treat late-stage colorectal cancer - a disease that kills more than 50,000 people each year in the United States. The team identified a novel mechanism by which colorectal cancer cells evade an anti-tumor immune response, which helped them develop an exosome-based therapeutic strategy to potentially treat the disease.

"Late-stage colorectal cancer patients face enormous challenges with current treatment options. Most of the time, the patient's immune system cannot efficiently fight against tumors, even with the ...

Seasonally occurring fields of aufeis (icing) constitute an important resource for the water supply of the local population in the Upper Indus Basin. However, little research has been done on them so far. Geographers at the South Asia Institute of Heidelberg University have now examined the spreading of aufeis and, for the first time, created a full inventory of these aufeis fields. The more than 3,700 accumulations of laminated ice are important for these high mountain areas between South and Central Asia, particularly with respect to hydrology and climatology.

In the semi-arid Himalaya regions of India and Pakistan, meltwater from snow and glaciers plays an essential role for irrigation in local agriculture and hydropower generation. In ...

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., April 28, 2021--Analysis of data from a lightning mapper and a small, hand-held radiation detector has unexpectedly shed light on what a gamma-ray burst from lightning might look like - by observing neutrons generated from soil by very large cosmic-ray showers. The work took place at the High Altitude Water Cherenkov (HAWC) Cosmic Ray Observatory in Mexico.

"This was an accidental discovery," said Greg Bowers, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and lead author of the study published in Geophysical Research Letters. "We set up this system to study terrestrial gamma-ray flashes - or gamma-ray bursts from lightning - that are ...

New research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine has shed light on the No. 1 cause of epilepsy deaths, suggesting a long-sought answer for why some patients die unexpectedly following an epileptic seizure.

The researchers found that a certain type of seizure is associated with sudden death in a mouse model of epilepsy and that death occurred only when the seizure induced failure of the respiratory system.

The new understanding will help scientists in their efforts to develop ways to prevent sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Based on their research, the UVA team has already identified potential approaches to stimulate breathing in the ...

Children and young adults with compromised immune systems, such as those undergoing cancer treatment, may experience a prolonged period of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and the extended duration of infection may increase the incidence of mutations. This case study was conducted by investigators at Children's Hospital Los Angeles and is published in the journal EBioMedicine.

Most people are infectious for about 10 days after first showing COVID-19 symptoms. In this study, researchers describe two children and a young adult with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 for months. ...

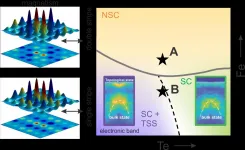

UPTON, NY--Scientists characterized how the electronic states in a compound containing iron, tellurium, and selenium depend on local chemical concentrations. They discovered that superconductivity (conducting electricity without resistance), along with distinct magnetic correlations, appears when the local concentration of iron is sufficiently low; a coexisting electronic state existing only at the surface (topological surface state) arises when the concentration of tellurium is sufficiently high. Reported in Nature Materials, their findings point to the composition range necessary for topological superconductivity. Topological superconductivity could enable more ...