(Press-News.org) Experimental Alzheimer's drugs have shown little success in slowing declines in memory and thinking, leaving scientists searching for explanations. But new research in mice has shown that some investigational Alzheimer's therapies are more effective when paired with a treatment geared toward improving drainage of fluid -- and debris -- from the brain, according to a study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The findings, published April 28 in the journal Nature, suggest that the brain's drainage system -- known as the meningeal lymphatics -- plays a pivotal but underappreciated role in neurodegenerative disease, and that repairing faulty drains could be a key to unlocking the potential of certain Alzheimer's therapies.

"The lymphatics are a sink," said co-senior author Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator. "Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and frontotemporal dementia are characterized by protein aggregation in the brain. If you break up these aggregates but you have no way to get rid of the debris because your sink is clogged, you didn't accomplish much. You have to unclog the sink to really solve the problem."

Sticky plaques of the protein amyloid start forming in the brains of people with Alzheimer's two decades or more before symptoms such as forgetfulness and confusion arise. For years, scientists have tried to treat Alzheimer's by developing therapies that clear away such plaques but have had very limited success. One of the most promising candidates, aducanumab, recently proved effective at slowing cognitive decline in one clinical trial but failed in another, leaving scientists baffled.

Kipnis, who is also a professor of neurosurgery, of neurology and of neuroscience, identified meningeal lymphatics as the brain's drainage system in 2015. A few years later, in 2018, he demonstrated that damage to the system increases amyloid buildup in mice. He suspects that the mixed and often disappointing performance of anti-amyloid drugs can be explained by differences in lymphatic function among Alzheimer's patients. But proving this hunch has been challenging, as there are no tools to measure the health of a person's meningeal lymphatics directly.

In this study, Kipnis and colleagues took an indirect approach to checking the drainage system in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. The study was undertaken in collaboration with biotherapeutics company PureTech Health.

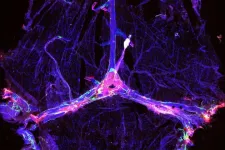

Thinking that the effects of a clogged drain might spill over onto microglia, the cells that serve as the brain's cleanup crew, the researchers looked for evidence of lymphatic damage in the form of altered patterns of microglial gene expression. Microglia play a complicated role in Alzheimer's disease: They seem to slow the growth of amyloid plaques early in the course of the disease but worsen neurological damage later on. The researchers disabled the meningeal lymphatics of a group of mice genetically prone to forming amyloid plaques, leaving the lymphatics functional in another group of mice for comparison, and analyzed the patterns of genes expressed by microglia.

Lymphatic dysfunction shifted microglia toward a state that was more likely to promote neurodegeneration. Further, when co-senior author Oscar Harari, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and of genetics, compared the gene-expression patterns in microglia from mice and people -- including 53 people who died with Alzheimer's disease and nine who died with healthy brains -- the people's microglia most resembled those from mice with damaged lymphatics.

"There was a signature we found in the microglia from mice with ablated meningeal lymphatics," Harari said. "When we harmonized the human and mouse microglial data, we found the same signature in the human data."

Another cell type, endothelial cells that line the inside of lymphatic vessels, provided additional evidence for the importance of the brain's drainage system. Co-senior author Carlos Cruchaga, PhD, a professor of psychiatry, of genetics and of neurology, identified the genes most highly expressed in lymphatic endothelial cells from mice. He discovered that genetic variations in many of the same genes have been linked to Alzheimer's in people, suggesting that problems with the lymphatics might contribute to the disease.

"In the end, even though we're looking at specific cell types and specific pathways, the brain is one big organ," Cruchaga said. "The lymphatic system is how the garbage is cleaned out of the brain. If it's not working, everything gets gummed up. If it starts working better, then everything in the brain works better. I think this is a very good example of how everything is connected, everything impacts brain health."

To find out whether bolstering lymphatic function could help treat Alzheimer's disease, the researchers studied mice genetically prone to developing amyloid plaques and whose lymphatics were impaired due to age or injury. They treated the animals with mouse versions of the experimental Alzheimer's drugs aducanumab or BAN2401, along with vascular endothelial growth factor C, a compound that promotes the growth of lymphatic vessels. Combination therapy reduced amyloid deposits more than the anti-amyloid drugs alone.

"There have been several antibodies that appear very effective at reducing amyloid deposits in mouse studies and now in humans," said co-author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology. "Some now also appear to slow cognitive decline in people with very mild dementia or mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's. However, the cognitive effects are not large, and one wonders if meningeal lymphatic system dysfunction may be related in part to the somewhat limited effects on cognition currently being observed. The meningeal lymphatic system seems to be influencing not just the progression of the amyloid component of Alzheimer's pathology but also the response to immunotherapy. Maybe an understanding of this system is a part of what the field of Alzheimer's drug development has been missing, and with increased attention to it we will better translate some of these promising drug candidates into therapies that provide meaningful benefits to people living with this devastating disease."

INFORMATION:

Is forest harvesting increasing in Europe? Yes, but not as much as reported last July in a controversial study published in Nature.

The study Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015, used satellite data to assess forest cover and claimed an abrupt increase of 69% in the harvested forest in Europe from 2016. The authors, from the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC), suggested that this increase resulted from expanding wood markets encouraged by EU bioeconomy and bioenergy policies. The publication triggered a heated debate, both scientific ...

What The Study Did: Length, readability and complexity of informed consent documents for the COVID-19 vaccine phase III randomized clinical trials were assessed in this quality improvement study.

Authors: Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10843)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

What The Study Did: The number of applicants and number of applications submitted per applicant to internal medicine residency and subspecialty fellowships for 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared with five prior application cycles in this study.

Authors: Laura A. Huppert, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8199)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated racial/ethnic differences in the performance of statistical models that use health record data to predict the risk of suicide after an outpatient mental health visit.

Authors: R. Yates Coley, Ph.D., of the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0493)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest ...

What The Study Did: The association between undergoing gender-affirming surgery and mental health outcomes was looked at in this study.

Authors: Anthony N. Almazan, B.A., of Harvard Medical School in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study and commentary ...

Enhancing the brain's lymphatic system when administering immunotherapies may lead to better clinical outcomes for Alzheimer's disease patients, according to a new study in mice. Results published April 28 in Nature suggest that treatments such as the immunotherapies BAN2401 or aducanumab might be more effective when the brain's lymphatic system can better drain the amyloid-beta protein that accumulates in the brains of those living with Alzheimer's. Major funding for the research was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), part of the National Institutes of Health, and all study data is now freely available ...

For the first time, scientists are able to study changes in the DNA of any human tissue, following the resolution of long-standing technical challenges by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. The new method, called nanorate sequencing (NanoSeq), makes it possible to study how genetic changes occur in human tissues with unprecedented accuracy.

The study, published today (28 April) in Nature, represents a major advance for research into cancer and ageing. Using NanoSeq to study samples of blood, colon, brain and muscle, the research also challenges the idea that cell division is the main mechanism ...

Models that can successfully predict suicides in a general population sample can perform poorly in some racial or ethnic groups, according to a study by Kaiser Permanente researchers published April 28 in JAMA Psychiatry.

The new findings show that 2 suicide prediction models are less accurate for Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native people and demonstrate how all prediction models should be evaluated before they are used. The study is believed to be the first to look at how the latest statistical methods to assess suicide risk perform when tested specifically in different ethnic and racial groups.

More ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., (April 28, 2021) - The latest, comprehensive data from The North American COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry was presented today as late-breaking clinical research at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions. Results reveal in these series of STEMI activations during the COVID era, patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were less likely to receive diagnostic angiograms. Those with COVID-19 positive status had higher in-hospital mortality. The prospective, ongoing observational registry was created under the guidance of the SCAI, Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology (CAIC) and American College of Cardiology (ACC). ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., (April 28, 2021) - Two new studies, presented today as late-breaking clinical science at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions, provide new treatment insights for cardiogenic shock (CS) patients. A study of the SCAI cardiogenic shock stages consensus document confirms the accuracy of the shock classification. In addition, an analysis of the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative demonstrates use of a shock protocol emphasizing early use of mechanical circulatory support may lead to improved survival for patients with CS.

CS is a rare, life-threatening ...