(Press-News.org) For the first time, scientists are able to study changes in the DNA of any human tissue, following the resolution of long-standing technical challenges by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. The new method, called nanorate sequencing (NanoSeq), makes it possible to study how genetic changes occur in human tissues with unprecedented accuracy.

The study, published today (28 April) in Nature, represents a major advance for research into cancer and ageing. Using NanoSeq to study samples of blood, colon, brain and muscle, the research also challenges the idea that cell division is the main mechanism driving genetic changes. The new method is also expected to allow researchers to study the effect of carcinogens on healthy cells, and to do so more easily and on a much larger scale than has been possible up until now.

The tissues in our body are composed of dividing and non-dividing cells. Stem cells renew themselves throughout our lifetimes and are responsible for supplying non-dividing cells to keep the body running. The vast majority of cells in our bodies are non-dividing or divide only rarely. They include granulocytes in our blood, which are produced in the billions every day and live for a very short time, or neurons in our brain, which live for much longer.

Genetic changes, known as somatic mutations, occur in our cells as we age. This is a natural process, with cells acquiring around 15-40 mutations per year. Most of these mutations will be harmless, but some of them can start a cell on the path to cancer.

Since the advent of genome sequencing in the late twentieth century, cancer researchers have been able to better understand the formation of cancers and how to treat them by studying somatic mutations in tumour DNA. In recent years, new technologies have also enabled scientists to study mutations in stem cells taken from healthy tissue.

But until now, genome sequencing has not been accurate enough to study new mutations in non-dividing cells, meaning that somatic mutation in the vast majority of our cells has been impossible to observe accurately.

In this new study, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute sought to refine an advanced sequencing method called duplex sequencing1. The team searched for errors in duplex sequence data and realised that they were concentrated at the ends of DNA fragments, and had other features suggesting flaws in the process used to prepare DNA for sequencing.

They then implemented improvements to the DNA preparation process, such as using specific enzymes to cut DNA more cleanly, as well as improved bioinformatics methods. Over the course of four years, accuracy was improved until they achieved fewer than five errors per billion letters of DNA.

Dr Robert Osborne, an alumnus of the Wellcome Sanger Institute who led the development of the method, said: "Detecting somatic mutations that are only present in one or a few cells is incredibly technically challenging. You have to find a single letter change among tens of millions of DNA letters and previous sequencing methods were simply not accurate enough. Because NanoSeq makes only a few errors per billion DNA letters, we are now able to accurately study somatic mutations in any tissue."

The team took advantage of NanoSeq's improved sensitivity to compare the rates and patterns of mutation in both stem cells and non-dividing cells in several human tissue types.

Surprisingly, analysis of blood cells found a similar number of mutations in slowly dividing stem cells and more rapidly dividing progenitor cells2. This suggested that cell division is not the dominant process causing mutations in blood cells. Analysis of non-dividing neurons and rarely dividing cells from muscle also revealed that mutations accumulate throughout life in cells without cell division, and at a similar pace to cells in the blood.

Dr Federico Abascal, the first author of the paper from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: "It is often assumed that cell division is the main factor in the occurrence of somatic mutations, with a greater number of divisions creating a greater number of mutations. But our analysis found that blood cells that had divided many times more than others featured the same rates and patterns of mutation. This changes how we think about mutagenesis and suggests that other biological mechanisms besides cell division are key."

The ability to observe mutation in all cells opens up new avenues of research into cancer and ageing, such as studying the effects of known carcinogens like tobacco or sun exposure, as well as discovering new carcinogens. Such research could greatly improve our understanding of how lifestyles choices and exposures to carcinogens can lead to cancer.

A further benefit of the NanoSeq method is the relative ease with which samples can be collected. Rather than taking biopsies of tissue, cells can be collected non-invasively, such as by scraping the skin or swabbing the throat.

Dr Inigo Martincorena, a senior author of the paper from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: "The application of NanoSeq on a small scale in this study has already led us to reconsider what we thought we knew about mutagenesis, which is exciting. NanoSeq will also make it easier, cheaper and less invasive to study somatic mutation on a much larger scale. Rather than analysing biopsies from small numbers of patients and only being able to look at stem cells or tumour tissue, now we can study samples from hundreds of patients and observe somatic mutations in any tissue."

INFORMATION:

Models that can successfully predict suicides in a general population sample can perform poorly in some racial or ethnic groups, according to a study by Kaiser Permanente researchers published April 28 in JAMA Psychiatry.

The new findings show that 2 suicide prediction models are less accurate for Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native people and demonstrate how all prediction models should be evaluated before they are used. The study is believed to be the first to look at how the latest statistical methods to assess suicide risk perform when tested specifically in different ethnic and racial groups.

More ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., (April 28, 2021) - The latest, comprehensive data from The North American COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry was presented today as late-breaking clinical research at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions. Results reveal in these series of STEMI activations during the COVID era, patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were less likely to receive diagnostic angiograms. Those with COVID-19 positive status had higher in-hospital mortality. The prospective, ongoing observational registry was created under the guidance of the SCAI, Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology (CAIC) and American College of Cardiology (ACC). ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., (April 28, 2021) - Two new studies, presented today as late-breaking clinical science at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions, provide new treatment insights for cardiogenic shock (CS) patients. A study of the SCAI cardiogenic shock stages consensus document confirms the accuracy of the shock classification. In addition, an analysis of the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative demonstrates use of a shock protocol emphasizing early use of mechanical circulatory support may lead to improved survival for patients with CS.

CS is a rare, life-threatening ...

WASHINGTON, D.C, (April 28, 2021) - An analysis of the prospective Fuwai PCI Registry, confirms long-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is an optimal treatment option for acute coronary syndrome patients (ACS) following a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The study shows long-term DAPT reduces ischemic events without increasing bleeding or other complications as compared to short-term DAPT treatments. The study was presented today as late-breaking clinical research at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography &Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions.

Following ACS, patients have a high risk of ischemic events, which impacts chances of survival. Patients are predisposed for blood clots ...

Chinese scientists have made direct observations in face-centered cubic VCoNi (medium)-entropy alloys (MEA) and for the first time proposed a convincing identification of subnanoscale chemical short-range order (CSRO). This achievement undisputedly resolves the pressing question of if, what and why CSRO exists, and how to explicitly identify CSRO.

This work, published in Nature on April 29, was conducted by Prof. WU Xiaolei from the Institute of Mechanics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in collaboration with Prof. MA En's team from Xi'an Jiaotong University and Prof. ZHU Jing's team from Tsinghua University.

Multi-principal element alloys--also known as high (medium)-entropy alloys (HEAs/MEAs)--are a hot and frontier topic in multidisciplinary fields. In these ...

Oxytocin and arginine vasopressin are two hormones in the endocrine system that can act as neurotransmitters and regulate -in vertebrates and invertebrates- a wide range of biological functions, such as bonding formation, breastfeeding, birth or arterial pressure. Biochemists in the pregenomic era, named these genes differently in different species, due to small protein coding differences.

A new study carried out by the University of Barcelona (UB) and the Rockefeller University, published in the journal Nature, has analysed and compared the genome of 35 species representing ...

Researchers have discovered an explanation for why cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs)--clusters of dilated blood vessels in the brain--can suddenly grow to cause seizures or stroke. Specifically, they found that a specific, acquired mutation in a cancer-causing gene (PIK3CA) could exacerbate existing CCMs in the brain. Furthermore, repurposing an already existing anticancer drug showed promise in mouse models of CCMs in improving brain-vascular health and preventing bleeding into the brain tissue.

Previous studies linked the initial formation of CCMs to various environmental factors, including ...

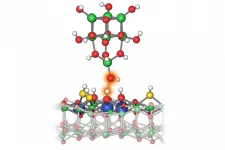

The degree of acidity or alkalinity of a substance is crucial for its chemical behavior. The decisive factor is the so-called proton affinity, which indicates how easily an entity accepts or releases a single proton. While it is easy to measure this for molecules, it has not been possible for surfaces. This is important because atoms on surfaces have very different proton affinities, depending on where they sit.

Researchers at TU Wien have now succeeded in making this important physical quantity experimentally accessible for the first time: Using a specially modified atomic force microscope, it is possible to study the proton affinity of individual atoms. This should help to analyze catalysts on an atomic scale. The results have been published in the scientific journal Nature.

Precision ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Tiny molecules called nanobodies, which can be designed to mimic antibody structures and functions, may be the key to blocking a tick-borne bacterial infection that remains out of reach of almost all antibiotics, new research suggests.

The infection is called human monocytic ehrlichiosis, and is one of the most prevalent and potentially life-threatening tick-borne diseases in the United States. The disease initially causes flu-like symptoms common to many illnesses, and in rare cases can be fatal if left untreated.

Most antibiotics can't build up ...

ATLANTA--Processed diets, which are low in fiber, may initially reduce the incidence of foodborne infectious diseases such as E. coli infections, but might also increase the incidence of diseases characterized by low-grade chronic infection and inflammation such as diabetes, according to researchers in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University.

This study used mice to investigate how changing from a grain-based diet to a highly processed, high-fat Western style diet impacts infection with the pathogen Citrobacter rodentium, which resembles Escherichia coli (E. coli) infections in humans. The findings are published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Gut microbiota, the microorganisms living in the intestine, provide a number of benefits, ...