Uncertainty of future Southern Ocean CO2 uptake cut in half

2021-04-28

(Press-News.org) Anyone researching the global carbon cycle has to deal with unimaginably large numbers. The Southern Ocean - the world's largest ocean sink region for human-made CO2 - is projected to absorb a total of about 244 billion tons of human-made carbon from the atmosphere over the period from 1850 to 2100 under a high CO2 emissions scenario. But the uptake could possibly be only 204 or up to 309 billion tons. That's how much the projections of the current generation of climate models vary. The reason for this large uncertainty is the complex circulation of the Southern Ocean, which is difficult to correctly represent in climate models.

"Research has been trying to solve this problem for a long time. Now we have succeeded in reducing the great uncertainty by about 50 percent," says Jens Terhaar of the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of Bern.

Together with Thomas Frölicher and Fortunat Joos, who are also researchers at the Oeschger Centre, Terhaar has just presented in the scientific journal "Sciences Advances" a new method for constraining the Southern Ocean's CO2 sink. The link between the uptake of human-made CO2 and the salinity of the surface waters is key to this. "The discovery that these two factors are closely related helped us to better constrain the future Southern Ocean CO2 sink " explains Thomas Frölicher.

Towards achieving the Paris climate target

A better constraint Southern Ocean carbon sink is a prerequisite to understand future climate change. The ocean absorbs at least one fifth of human-made CO2 emissions, and as such slows down global warming. By far the largest part of this uptake, about 40 percent, occurs in the Southern Ocean.

The new calculations from Bern not only reduce uncertainties in CO2 uptake and thus allow more accurate projections, but also show that by the end of the 21st century the Southern Ocean will absorb around 15 percent more CO2 than previously thought. This is only a tiny bit of help on the extremely challenging path to achieving the Paris temperature goal of 1.5 degree. "The reduction of human-made CO2 emissions resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels remains extremely urgent if we are to achieve the goals of the Paris climate agreement," clarifies Fortunat Joos.

Better model predictions possible

In their study, the three climate scientists show why the salinity content of the ocean surface waters is a good indicator of how much human-made CO2 is transported into the ocean interior. Models that simulate low salinity in the Southern Ocean surface waters have too light waters and therefore transport less water and CO2 into the ocean interior. As a result, they also absorb less CO2 from the atmosphere. Models with higher salinity, on the other hand, show higher absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere. The salinity of the Southern Ocean surface waters, determined through observations, allowed the researchers from Bern to narrow down the uncertainty in the various model projections.

INFORMATION:

Publication details:

J. Terhaar, T. L. Frölicher, F. Joos: Southern Ocean anthropogenic carbon sink constrained by sea surface salinity. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd5964 (2021), April 28, 2021, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd5964 https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/7/18/eabd5964

Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

The Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research (OCCR) is one of the strategic centers of the University of Bern. It brings together researchers from 14 institutes and four faculties. The OCCR conducts interdisciplinary research right on the frontline of climate change research. The Oeschger Centre was founded in 2007 and bears the name of Hans Oeschger (1927-1998), a pioneer of modern climate research, who worked in Bern.

http://www.oeschger.unibe.ch

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-28

A protein variant common in malignant bladder tumor cells may serve as a new avenue for treating bladder cancer. A multi-institution study led by END ...

2021-04-28

Veterinarians, pet owners and breeders often have preconceived notions about each other, but by investigating these biases, experts at the University of Arizona College of Veterinary Medicine hope to improve both human communication and animal care.

"Veterinary medicine may require us to treat the patient, but we are unable to improve pet patient outcomes without human client consent and trust. Communication is an essential component of veterinary practice," said Ryane Englar, an associate professor and the director of veterinary skills development for the college. "As an anecdotal example, vets and breeders don't always get along, but there was no research on these subjects. I wondered, what do the groups want and need? If ...

2021-04-28

Washington, D.C. - April 28, 2021 - As of April 2021, more than 3 million people worldwide have died of COVID-19. Early in the pandemic, researchers developed accurate diagnostic tests and identified health conditions that correlated with worse outcomes. However, a clinical predictor of who faces the highest risk of being hospitalized, put on a ventilator or dying from the disease has remained largely out of reach.

This week in mSphere, an open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, researchers describe a two-step prognostic test that can help predict a patient's response to infection with SARS-CoV-2. The test combines a disease risk factor score with a test ...

2021-04-28

LAWRENCE -- College students across the country struggle with a vicious cycle: Test anxiety triggers poor sleep, which in turn reduces performance on the tests that caused the anxiety in the first place.

New research from the University of Kansas just published in the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine is shedding light on this biopsychosocial process that can lead to poor grades, withdrawal from classes and even students who drop out. Indeed, about 40% of freshman don't return to their universities for a second year in the United States.

"We were interested ...

2021-04-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Socially just policies aimed at limiting the Earth's human population hold tremendous potential for advancing equity while simultaneously helping to mitigate the effects of climate change, Oregon State University researchers say.

In a paper published this week in Sustainability Science, William Ripple and Christopher Wolf of the OSU College of Forestry also note that fertility rates are a dramatically understudied and overlooked aspect of the climate emergency. That's especially true relative to the attention devoted to other climate-related topics including energy, short-lived pollutants and ...

2021-04-28

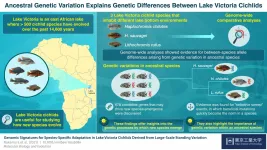

Biologists use the term adaptive radiation to describe a phenomenon in which new species rapidly evolve from an ancestral species, often in response to changes in the local environment that lead to new biological niches becoming available. To understand this process, biologists often turn to the cichlids of Lake Victoria, in which over 500 species of the fish have evolved over the past 14,600 years. As Professor Masato Nikaido of Tokyo Tech explains, "The level of genetic differentiation among species is considered very low due to the short period of time after these different species began evolving, and this limited genetic differentiation provides us with a great opportunity to find candidate genes that have contributed to adaptive ...

2021-04-28

Predatory bacteria--bacteria that eat other bacteria--grow faster and consume more resources than non-predators in the same soil, according to a new study out this week from Northern Arizona University. These active predators, which use wolfpack-like behavior, enzymes, and cytoskeletal 'fangs' to hunt and feast on other bacteria, wield important power in determining where soil nutrients go. The results of the study, published in the journal mBio this week, show predation is an important dynamic in the wild microbial realm, and suggest that these predators play an outsized role in how elements are stored in or released from soil.

Like every other life form on earth, bacteria belong to intricate food webs in which organisms are connected ...

2021-04-28

Constantina Theofanopoulou wanted to study oxytocin. Her graduate work had focused on how the hormone influences human speech development, and now she was preparing to use those findings to investigate how songbirds learn to sing. The problem was that birds do not have oxytocin. Or so she was told.

"Everywhere that I looked in the genome," she says, "I was unable to find a gene called oxytocin in birds."

Theofanopoulou eventually came across mesotocin, the analogue for oxytocin in birds, reptiles, and amphibians. But as she plumped the literature in Erich Jarvis's lab at Rockefeller, the waters grew muddier. If she and Jarvis wanted to find studies on oxytocin in fish, they ...

2021-04-28

Researchers from Erasmus School of Economics, IESE Business School, and New York University published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that examines what business schools do wrong when conducting academic research and what changes they can make so that research contributes to improving society.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Faculty Research Incentives and Business School Health: A New Perspective from and for Marketing" and is authored by Stefan Stremersch, Russell Winer, and Nuno Camacho.

In February 2020, an article in ...

2021-04-28

The flightless kakapo of New Zealand is in trouble. The world's heaviest parrot--representing one of the most ancestral branches of the parrot family tree--is nearly extinct, with barely 200 adults plodding the underbrush of four small islands. Whether the last of the kakapos had the genetic resilience to survive was a question that only high-quality genomic analysis could answer.

But a high-quality genome assembly did not exist for the kakapo--nor for most of the 70,000 vertebrate species alive today.

Questions about how best to prevent the extinction of species ranging ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Uncertainty of future Southern Ocean CO2 uptake cut in half