(Press-News.org) Nearly one quarter of the land in the Northern Hemisphere, amounting to some 9 million square miles, is layered with permafrost -- soil, sediment, and rocks that are frozen solid for years at a time. Vast stretches of permafrost can be found in Alaska, Siberia, and the Canadian Arctic, where persistently freezing temperatures have kept carbon, in the form of decayed bits of plants and animals, locked in the ground.

Scientists estimate that more than 1,400 gigatons of carbon is trapped in the Earth's permafrost. As global temperatures climb, and permafrost thaws, this frozen reservoir could potentially escape into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and methane, significantly amplifying climate change. However, little is known about permafrost's stability, today or in the past.

Now geologists at MIT, Boston College, and elsewhere have reconstructed permafrost's history over the last 1.5 million years. The researchers analyzed cave deposits in locations across western Canada and found evidence that, between 1.5 million and 400,000 years ago, permafrost was prone to thawing, even in high Arctic latitudes. Since then, however, permafrost thaw has been limited to sub-Arctic regions.

The results, published in Science Advances, suggest that the planet's permafrost shifted to a more stable state in the last 400,000 years, and has been less susceptible to thawing since then. In this more stable state, permafrost likely has retained much of the carbon that it has built up during this time, having little opportunity to gradually release it.

"The stability of the last 400,000 years may actually work against us, in that it has allowed carbon to steadily accumulate in permafrost over this time. Melting now might lead to substantially greater releases of carbon to the atmosphere than in the past," says study co-author David McGee, associate professor in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences.

McGee's co-authors are Ben Hardt and Irit Tal at MIT; Nicole Biller-Celander, Jeremy Shakun, and Corinne Wong at Boston College; Alberto Reyes at the University of Alberta; Bernard Lauriol at the University of Ottawa; and Derek Ford at McMaster University.

Stacked warming

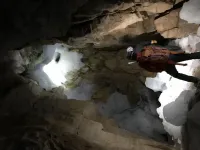

Periods of past warming are considered interglacial periods, or times between global ice ages. These geologically brief windows can warm permafrost enough to thaw. Signs of ancient permafrost thaw can be seen in stalagmites and other mineral deposits left behind as water moves through the ground and into caves. These caves, particularly at high Arctic latitudes, are often remote and difficult to access, and as a result, there has been little known about the history of permafrost, and its past stability in warming climates.

However, in 2013, researchers at Oxford University were able to sample cave deposits from a few locations across Siberia; their analysis suggested that permafrost thaw was widespread throughout Siberia prior to 400,000 years ago. Since then, the results showed a much-reduced range of permafrost thaw.

Shakun and Biller-Celander wondered whether the trend toward a more stable permafrost was a global one, and looked to carry out similar studies in Canada to reconstruct the permafrost history there. They linked up with pioneering cave scientists Lauriol and Ford, who provided samples of cave deposits that they collected over the years from three distinct permafrost regions: the southern Canadian Rockies, Nahanni National Park in the Northwest Territories, and the northern Yukon.

In total, the team obtained 74 samples of speleothems, or sections of stalagmites, stalactites, and flowstones, from at least five caves in each region, representing various cave depths, geometries, and glacial histories. Each sampled cave was located on exposed slopes that were likely the first parts of the permafrost landscape to thaw with warming.

The samples were flown to MIT, where McGee and his lab used precise geochronology techniques to determine the ages of each sample's layers, each layer reflecting a period of permafrost thaw.

"Each speleothem was deposited over time like stacked traffic cones," says McGee. "We started with the outermost, youngest layers to date the most recent time that the permafrost thawed."

Arctic shift

McGee and his colleagues used techniques of uranium/thorium geochronology to date the layers of each speleothem. The dating technique relies on the natural decay process of uranium to its daughter isotope, thorium 230, and the fact that uranium is soluble in water, whereas thorium is not.

"In the rocks above the cave, as waters percolate through, they accumulate uranium and leave thorium behind," McGee explains. "Once that water gets to the stalagmite surface and precipitates at time zero, you have uranium, and no thorium. Then gradually, uranium decays and produces thorium."

The team drilled out small amounts from each sample and dissolved them through various chemical steps to isolate uranium and thorium. Then they ran the two elements through a mass spectrometer to measure their amounts, the ratio of which they used to calculate a given layer's age.

From their analysis, the researchers observed that samples collected from the Yukon and the farthest northern sites bore samples no younger than 400,000 years old, suggesting permafrost thaw has not occurred in those sites since then.

"There may have been some shallow thaw, but in terms of the entire rock above the cave being thawed, that hasn't occurred for the last 400,000 years, and was much more common prior to that," McGee says.

The results suggest that the Earth's permafrost was much less stable prior to 400,000 years ago and was more prone to thawing, even during interglacial periods when levels of temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide were on par with modern levels, as other work has shown.

"To see this evidence of a much less stable Arctic prior to 400,000 years ago, suggests even under similar conditions, the Arctic can be a very different place," McGee says. "It raises questions for me about what caused the Arctic to shift into this more stable condition, and what can cause it to shift out of it."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation, the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Polar Continental Shelf Program.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Chestnut Hill, Mass. (4/28/2021) -- The vast frozen terrain of Arctic permafrost thawed several times in North America within the past 1 million years when the world's climate was not much warmer than today, researchers from the United States and Canada report in today's edition of Science Advances.

Arctic permafrost contains twice as much carbon as the atmosphere. But the researchers found that the thawings -- which expel stores of carbon dioxide sequestered deep in frozen vegetation -- were not accompanied by increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere. The surprising finding runs counter to predictions that as the planet ...

About a quarter of a percent of the entire gross domestic product of industrialized countries is estimated to be lost through a single technical issue: the fouling of heat exchanger surfaces by salts and other dissolved minerals. This fouling lowers the efficiency of multiple industrial processes and often requires expensive countermeasures such as water pretreatment. Now, findings from MIT could lead to a new way of reducing such fouling, and potentially even enable turning that deleterious process into a productive one that can yield saleable products.

The findings are the result of years of work by recent MIT graduates Samantha McBride PhD '20 and Henri-Louis Girard PhD '20 with professor of mechanical ...

Two teams have created a new generation of highly specific CAR T cells, which safely cleared solid tumors in mice with mesothelioma, ovarian cancer, and the deadly brain cancer glioblastoma while outlasting and outperforming conventional CAR T cell designs. The results suggest these cells could minimize the risk of dangerous side effects and address the traditionally poor performance of CAR T cells against solid tumors in the clinic. CAR T cells are genetically modified human T cells and have shown impressive performance in patients with leukemia. However, CAR T cells don't work as well against solid tumors, as these cancers lack molecular targets that the cells can easily recognize. ...

The number of distinctive sources and voices on the internet is proven to be in long-term decline, according to new research.

A paper entitled 'Evolution of diversity and dominance of companies in online activity' published in the PLOS ONE scientific journal has shown between 60 and 70 percent of all attention on key social media platforms in different market segments is focused towards just 10 popular domains.

In stark contrast, new competitors are struggling to survive against such dominant players, with just 3 percent of online domains born in 2015 still active today, compared to nearly 40 percent of those formed back in 2006.

The researchers say ...

The subseafloor constitutes one of the largest and most understudied ecosystems on Earth. While it is known that life survives deep down in the fluids, rocks, and sediments that make up the seafloor, scientists know very little about the conditions and energy needed to sustain that life.

An interdisciplinary research team, led from ASU and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), sought to learn more about this ecosystem and the microbes that exist in the subseafloor. The results of their findings were recently published in Science Advances, with ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration assistant professor and geobiologist ...

Organ development in plants mostly occurs through combinatorial activity of so-called meristems. Meristems are plant cells or tissues that give rise to new organs, similar to stem cells in human - including spikelets. Spikelets are components of the spike and form florets (flowers) themselves, which in turn produce grains after fertilisation.

Inflorescence morphogenesis in grasses (Poaceae) is complex and based on a specialised floral meristem, the spikelet meristem, from which all other floral organs arise and which also gives rise to the grain. The fate of the spikelet thus determines not only reproductive success, ...

DETROIT (April 28, 2021) - The results of a large, national heart attack study show that patients with a deadly complication known as cardiogenic shock survived at a significantly higher rate when treated with a protocol developed by cardiologists at Henry Ford Hospital in END ...

Anyone researching the global carbon cycle has to deal with unimaginably large numbers. The Southern Ocean - the world's largest ocean sink region for human-made CO2 - is projected to absorb a total of about 244 billion tons of human-made carbon from the atmosphere over the period from 1850 to 2100 under a high CO2 emissions scenario. But the uptake could possibly be only 204 or up to 309 billion tons. That's how much the projections of the current generation of climate models vary. The reason for this large uncertainty is the complex circulation of the Southern Ocean, which ...

A protein variant common in malignant bladder tumor cells may serve as a new avenue for treating bladder cancer. A multi-institution study led by END ...

Veterinarians, pet owners and breeders often have preconceived notions about each other, but by investigating these biases, experts at the University of Arizona College of Veterinary Medicine hope to improve both human communication and animal care.

"Veterinary medicine may require us to treat the patient, but we are unable to improve pet patient outcomes without human client consent and trust. Communication is an essential component of veterinary practice," said Ryane Englar, an associate professor and the director of veterinary skills development for the college. "As an anecdotal example, vets and breeders don't always get along, but there was no research on these subjects. I wondered, what do the groups want and need? If ...