How does the brain flexibly process complex information?

A new study reveals the mechanisms that support our brain's ability to adapt the way it processes information in our environment

2021-04-29

(Press-News.org) Human decision-making depends on the flexible processing of complex information, but how the brain may adapt processing to momentary task demands has remained unclear. In a new article published in the journal Nature Communications, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development have now outlined several crucial neural processes revealing that our brain networks may rapidly and flexibly shift from a rhythmic to a "noisy" state when the need to process information increases.

Driving a car, deliberating over different financial options, or even pondering different life paths requires us to process an overwhelming amount of information. But not all decisions pose equal demands. In some situations, decisions are easier because we already know which pieces of information are relevant. In other situations, uncertainty about which information is relevant for our decision requires us to get a broader picture of all available information sources. The mechanisms by which the brain flexibly adapts information processing in such situations were previously unknown.

To reveal these mechanisms, researchers from the Lifespan Neural Dynamics Group (LNDG) at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research designed a visual task. Participants were asked to view a moving cloud of small squares that differed from each other along the four visual dimensions: color, size, brightness, and movement direction. Participants were then asked a question about one of the four visual dimensions. For example, "Were more squares moving to the left, or right?". Prior to seeing the squares, the study authors manipulated "uncertainty" by informing participants which feature(s) they could be asked about; the more features that were relevant, the more uncertain participants were expected to become about which features to focus upon. Throughout the task, brain activity was measured using electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

First, the authors found that when participants were more uncertain about the relevant feature in the upcoming choice, participants' EEG signals shifted from a rhythmic mode (present when participants could focus on a single feature) to a more arrhythmic, "noisy" mode. "Brain rhythms may be particularly useful when we need to select relevant over irrelevant inputs, while increased neural 'noise' could make our brains more receptive to multiple sources of information. Our results suggest that the ability to shift back and forth between these rhythmic and 'noisy' states may enable flexible information processing in the human brain," says Julian Q. Kosciessa, LNDG post-doc and the article's first author.

Additionally, the authors found that the extent to which participants shifted from a rhythmic to a noisy mode in their EEG signals was dominantly coupled with increased fMRI activity in the thalamus, a deep brain structure largely inaccessible by EEG. The thalamus is often thought of primarily as an interface for sensory and motor signals, while its potential role in flexibility has remained elusive. The findings of the study may thus have broad implications for our current understanding of the brain structures required for us to adapt to an ever-changing world. "When neuroscientists think about how the brain enables behavioral flexibility, we often focus exclusively on networks in the cortex, while the thalamus is traditionally considered a simple relay for sensorimotor information. Instead, our results argue that the thalamus may support neural dynamics in general and could optimize brain states according to environmental demands, allowing us to make better decisions," says Douglas Garrett, senior author of the study and LNDG group leader.

In the next phases of their research, the authors plan to investigate the underlying neurochemical bases of how the thalamus permits shifts in neural dynamics, and whether such shifts can be "tuned" by stimulating the thalamus using weak electrical currents.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-29

People with diabetes are at increased risk of developing a severe course of COVID-19 compared to people without diabetes. The question to be answered is whether all people with diabetes have an increased risk of severe COVID-19, or whether specific risk factors can also be identified within this group. A new study by DZD researchers has now focused precisely on this question and gained relevant insights.

The COVID-19 pandemic poses unprecedented challenges to science and the health sector. While in some people with a SARS-CoV-2 infection the disease is hardly noticeable, in others ...

2021-04-29

Exposure before birth to persistent organic pollutants (POPs)-- organochlorine pesticides, industrial chemicals, etc.--may increase the risk in adolescence of metabolic disorders, such as obesity and high blood pressure. This was the main conclusion of a study by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a research centre supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation. The study was based on data from nearly 400 children living in Menorca, who were followed from before birth until they reached 18 years of age.

POPs are toxic, degradation-resistant ...

2021-04-29

A top-level international research team including researchers from the University of Eastern Finland has developed a new algorithm for the diagnostics of dementia. The algorithm is based on blood and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measurements. These biomarkers can be used to aid setting of an exact diagnosis already in the early phases of dementia.

Researchers from the University of Eastern Finland and the University of Oulu in collaboration with an international team have created a new diagnostic biomarker-based algorithm for the diagnostics of dementia. The team is led by Professor Barbara Borroni from the University of Brescia, Italy. The article was published in the Diagnostics journal.

The accurate diagnosis ...

2021-04-29

The proliferation of electric cars, smartphones, and portable devices is leading to an estimated 25 percent increase globally in the manufacturing of rechargeable batteries each year. Many raw materials used in the batteries, such as cobalt, may soon be in short supply. The European Commission is preparing a new battery decree, which would require the recycling of 95 percent of the cobalt in batteries. Yet existing battery recycling methods are far from perfect.

Researchers at Aalto University have now discovered that electrodes in lithium batteries containing cobalt can be reused as is after being newly saturated with lithium. In comparison to traditional recycling, which typically ...

2021-04-29

Glaciers are a sensitive indicator of climate change - and one that can be easily observed. Regardless of altitude or latitude, glaciers have been melting at a high rate since the mid-?20th century. Until now, however, the full extent of ice loss has only been partially measured and understood. Now an international research team led by ETH Zurich and the University of Toulouse has authored a comprehensive study on global glacier retreat, which was published online in Nature on 28 April. This is the first study to include all the world's glaciers - around 220,000 in total - excluding the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. The study's spatial and temporal resolution is unprecedented - and shows how rapidly glaciers have lost thickness and mass over the past two decades.

Rising sea levels ...

2021-04-29

Spreading of the seafloor in the Red Sea basin is found to have begun along its entire length around 13 million years ago, making its underlying oceanic crust twice as old as previously believed.

The formation history and age of the Red Sea basin has long been contested, largely because the crust under the sea is widely overlain by thick layers of salt and sediment, making it difficult to observe directly.

"Existing geological models of the Red Sea often contradict each other, largely due to limited high-resolution data and the influence of overlaying salt layers," says Froukje van der Zwan from KAUST, who worked on the project. "For example, ...

2021-04-29

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG, or LGG, is the most studied probiotic bacterium in the world. However, its features are not perfect, as it is unable to utilise the milk carbohydrate lactose or break down the milk protein casein. This is why the bacterium grows poorly in milk and why it has to be separately added to probiotic dairy products.

In fact, attempts have been made to make L. rhamnosus GG better adjust to milk through genetic engineering. However, strict restrictions have prevented the use of such modified bacteria in human food.

Thanks to a recent breakthrough made at the University of Helsinki, Finland, with researchers from the National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetic ...

2021-04-29

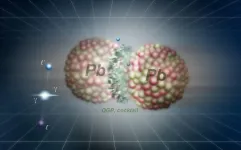

When heavy ions, accelerated to the speed of light, collide with each other in the depths of European or American accelerators, quark-gluon plasma is formed for fractions of a second, or even its "cocktail" seasoned with other particles. According to scientists from the IFJ PAN, experimental data show that there are underestimated actors on the scene: photons. Their collisions lead to the emission of seemingly excess particles, the presence of which could not be explained.

Quark-gluon plasma is undoubtedly the most exotic state of matter thus far known to us. In the LHC at CERN near Geneva, it is formed during central collisions of two lead ions ...

2021-04-29

Older people with vision loss are significantly more likely to suffer mild cognitive impairment, which can be a precursor to dementia, according to a new study published in the journal Ageing Clinical and Experimental Research.

The research by Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) examined World Health Organisation data on more than 32,000 people and found that people with loss in both near and far vision were 1.7 times more likely to suffer from mild cognitive impairment.

People with impairment of their near vision were 1.3 times more likely to suffer from mild cognitive impairment than someone with no vision impairment.

However, people who reported ...

2021-04-29

CLEVELAND--Using ultra-high field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to map the brains of people with Down syndrome (DS), researchers from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals and other institutions detected subtle differences in the structure and function of the hippocampus--a region of the brain tied to memory and learning.

Such detailed mapping, made possible by the high-powered MRI, is significant because it allowed the research team to better understand how each subregion of the hippocampus in people with DS is functionally connected to other parts of the brain. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How does the brain flexibly process complex information?

A new study reveals the mechanisms that support our brain's ability to adapt the way it processes information in our environment