One common kitchen scrap in Africa -- shells of ostrich eggs -- is now helping unscramble the mystery of when these changes took place, providing a timeline for some of the earliest Homo sapiens who settled down to utilize marine food resources along the South African coast more than 100,000 years ago.

Geochronologists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Berkeley Geochronology Center (BGC) have developed a technique that uses these ubiquitous discards to precisely date garbage dumps -- politely called middens -- that are too old to be dated by radiocarbon or carbon-14 techniques, the standard for materials like bone and wood that are younger than about 50,000 years.

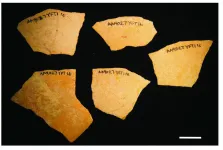

In a paper published this month in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, former UC Berkeley doctoral student Elizabeth Niespolo and geochronologist and BGC and associate director Warren Sharp reported using uranium-thorium dating of ostrich eggshells to establish that a midden outside Cape Town, South Africa, was deposited between 119,900 and 113,100 years ago.

That makes the site, called Ysterfontein 1, the oldest known seashell midden in the world, and implies that early humans were fully adapted to coastal living by about 120,000 years ago. This also establishes that three hominid teeth found at the site are among the oldest Homo sapiens fossils recovered in southern Africa.

The technique is precise enough for the researchers to state convincingly that the 12.5-foot-deep pile of mostly marine shells -- mussels, mollusks and limpets -- intermixed with animal bones and eggshells may have been deposited over a period of as little as 2,300 years.

The new ages are already revising some of the assumptions archeologists had made about the early Homo sapiens who deposited their garbage at the site, including how their population and foraging strategies changed with changing climate and sea level.

"The reason why this is exciting is that this site wouldn't have been datable by radiocarbon because it is too old," Niespolo said, noting that there are a lot more such sites around Africa, in particular the coastal areas of South Africa.

"Almost all of this sort of site have ostrich eggshells, so now that we have this technique, there is this potential to go and revisit these sites and use this approach to date them more precisely and more accurately, and more importantly, find out if they are the same age as Ysterfontein or older or younger, and what that tells us about foraging and human behavior in the past," she added.

Because ostrich eggshells are ubiquitous in African middens -- the eggs are a rich source of protein, equivalent to about 20 chicken eggs -- they have been an attractive target for geochronologists. But applying uranium-thorium dating -- also called uranium series -- to ostrich shells has been beset by many uncertainties.

"The previous work to date eggshells with uranium series has been really hit and miss, and mostly miss," Niespolo said.

Precision dating pushed back to 500,000 years ago

Other methods applicable to sites older than 50,000 years, such as luminescence dating, are less precise -- often by a factor of 3 or more -- and cannot be performed on archival materials available in museums, Sharp said.

The researchers believe that uranium-thorium dating can provide ages for ostrich eggshells as old as 500,000 years, extending precise dating of middens and other archeological sites approximately 10 times further into the past.

"This is the first published body of data that shows that we can get really coherent results for things well out of radiocarbon range, around 120,000 years ago in this case," said Sharp, who specializes in using uranium-thorium dating to solve problems in paleoclimate and tectonics as well as archeology. "It is showing that these eggshells maintain their intact uranium-series systems and give reliable ages farther back in time than had been demonstrated before."

"The new dates on ostrich eggshell and excellent faunal preservation make Ysterfontein 1 the as-yet best dated multi-stratified Middle Stone Age shell midden on the South African west coast," said co-author Graham Avery, an archeozoologist and retired researcher with the Iziko South African Museum. "Further application of the novel dating method, where ostrich eggshell fragments are available, will strengthen chronological control in nearby Middle Stone Age sites, such as Hoedjiespunt and Sea Harvest, which have similar faunal and lithic assemblages, and others on the southern Cape coast."

The first human settlements?

Ysterfontein 1 is one of about a dozen shell middens scattered along the western and eastern coasts of Western Cape Province, near Cape Town. Excavated in the early 2000s, it is considered a Middle Stone Age site established around the time that Homo sapiens were developing complex behaviors such as territoriality and intergroup competition, as well as cooperation among non-kin groups. These changes may be due to the fact that these groups were transitioning from hunter-gatherers to settled populations, thanks to stable sources of high-quality protein -- shellfish and marine mammals -- from the sea.

Until now, the ages of Middle Stone Age sites like Ysterfontein 1 have been uncertain by about 10%, making comparison among Middle Stone Age sites and with Later Stone Age sites difficult. The new dates, with a precision of about 2% to 3%, place the site in the context of well-documented changes in global climate: it was occupied immediately after the last interglacial period, when sea level was at a high, perhaps 8 meters (26 feet) higher than today. Sea level dropped rapidly during the occupation of the site -- the shoreline retreated up to 2 miles during this period -- but the accumulation of shells continued steadily, implying that the inhabitants found ways to accommodate the changing distribution of marine food resources to maintain their preferred diet.

The study also shows that the Ysterfontein 1 shell midden accumulated rapidly -- perhaps about 1 meter (3 feet) every 1,000 years --- implying that Middle Stone Age people along the southern African coast made extensive use of marine resources, much like people did during the Later Stone Age, and suggesting that effective marine foraging strategies developed early.

For dating, eggshells are better

Ages can be attached to some archeological sites older than 50,000 years through argon-argon (40Ar/39Ar) dating of volcanic ash. But ash isn't always present. In Africa, however -- and before the Holocene, throughout the Middle East and Asia -- ostrich eggshells are common. Some sites even contain ostrich eggshell ornaments made by early Homo sapiens.

Over the last four years, Sharp and Niespolo conducted a thorough study of ostrich eggshells, including analysis of modern eggshells obtained from an ostrich farm in Solvang, California, and developed a systematic way to avoid the uncertainties of earlier analyses. One key observation was that animals, including ostriches, do not take up and store uranium, even though it is common at parts-per-billion levels in most water. They demonstrated that newly laid ostrich shells contain no uranium, but that it is absorbed after burial in the ground.

The same is true of seashells, but their calcium carbonate structure -- a mineral called aragonite -- is not as stable when buried in soil as the calcite form of calcium carbonate found in eggshell. Because of this, eggshells retain better the uranium taken up during the first hundred years or so that that they are buried. Bone, consisting mostly of calcium phosphate, has a mineral structure that also does not remain stable in most soil environments nor reliably retains absorbed uranium.

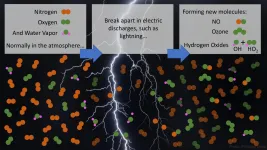

Uranium is ideal for dating because it decays at a constant rate over time to an isotope of thorium that can be measured in minute amounts by mass spectrometry. The ratio of this thorium isotope to the uranium still present tells geochronologists how long the uranium has been sitting in the eggshell.

Uranium-series dating relies on uranium-238, the dominant uranium isotope in nature, which decays to thorium-230. In the protocol developed by Sharp and Niespolo, they used a laser to aerosolize small patches along a cross-section of the shell, and ran the aerosol through a mass spectrometer to determine its composition. They looked for spots high in uranium and not contaminated by a second isotope of thorium, thorium-232, which also invades eggshells after burial, though not as deeply. They collected more material from those areas, dissolved it in acid, and then analyzed it more precisely for uranium-238 and thorium-230 with "solution" mass spectrometry.

These procedures avoid some of the previous limitations of the technique, giving about the same precision as carbon-14, but over a time range that is 10 times larger.

"The key to this dating technique that we have developed that differs from previous attempts to date ostrich egg shells is the fact that we are explicitly accounting for the fact that ostrich eggshells have no primary uranium in them, so the uranium that we are using to date the eggshells actually comes from the soil pore water and the uranium is being taken up by the eggshells upon deposition," Niespolo said.

INFORMATION:

Working with UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology Todd Dawson, Niespolo also analyzed other isotopes in eggshells -- stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen -- to establish that the climate rapidly became drier and cooler over the period of occupation, consistent with known climate changes at that time.

Niespolo, now a postdoctoral fellow at the California Institute of Technology but soon to be an assistant professor at Princeton University, is working with Sharp to date middens at other sites near Ysterfontein. She also is developing the uranium-series technique to use with other types of eggs, such as those of emus in Australia and rheas in South America, as well as the eggs of now extinct flightless birds, such as the two-meter (6.6-foot) tall Genyornis, which died out some 50,000 years ago in Australia.

The work was supported by the Leakey Foundation, Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation and National Science Foundation (BCS-1727085).