(Press-News.org) Scientists have been able to track how a multi-drug resistant organism is able to evolve and spread widely among cystic fibrosis patients - showing that it can evolve rapidly within an individual during chronic infection. The researchers say their findings highlight the need to treat patients with Mycobacterium abscessus infection immediately, counter to current medical practice.

Around one in 2,500 children in the UK is born with cystic fibrosis, a hereditary condition that causes the lungs to become clogged up with thick, sticky mucus. The condition tends to decrease life expectancy among patients.

In recent years, M. abscessus, a species of multi-drug resistant bacteria, has emerged as a significant global threat to individuals with cystic fibrosis and other lung diseases. It can cause a severe pneumonia leading to accelerated inflammatory damage to the lungs, and may prevent safe lung transplantation. It is also extremely difficult to treat - fewer than one in three cases is treated successfully.

In a study published today in Science, a team led by scientists at the University of Cambridge examined whole genome data for 1,173 clinical M. abscessus samples taken from 526 patients to study how the organism has evolved - and continues to evolve. The samples were obtained from cystic fibrosis clinics in the UK, as well as centres in Europe, the USA and Australia.

The team found two key processes that play an important part in the organism's evolution. The first is known as horizontal gene transfer - a process whereby the bacteria pick up genes or sections of DNA from other bacteria in the environment. Unlike classical evolution, which is a slow, incremental process, horizontal gene transfer can lead to big jumps in the pathogen's evolution, potentially allowing it to become suddenly much more virulent.

The second process is within-host evolution. As a consequence of the shape of the lung, multiple versions of the bacteria can evolve in parallel - and the longer the infection exists, the more opportunities they have to evolve, with the fittest variants eventually winning out. Similar phenomena have been seen in the evolution of new SARS-CoV-2 variants in immunocompromised patients.

Professor Andres Floto, joint senior author from the Centre for AI in Medicine (CCAIM) and the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge and the Cambridge Centre for Lung Infection at Royal Papworth Hospital, said: "What you end up with is parallel evolution in different parts of an individual's lung. This offers bacteria the opportunity for multiple rolls of the dice until they find the most successful mutations. The net result is a very effective way of generating adaptations to the host and increasing virulence.

"This suggests that you might need to treat the infection as soon as it is identified. At the moment, because the drugs can cause unpleasant side effects and have to be administered over a long period of time - often as long as 18 months - doctors usually wait to see if the bacteria cause illness before treating the infection. But what this does is give the bug plenty of time to evolve repeatedly, potentially making it more difficult to treat."

Professor Floto and colleagues have previously advocated routine surveillance of cystic fibrosis patients to check for asymptomatic infection. This would involve patients submitting sputum samples three or four times a year to check for the presence of M. abscessus infection. Such surveillance is carried out routinely in many centres in the UK.

Using mathematical models, the team have been able to step backwards through the organism's evolution in a single individual and recreate its trajectory, looking for key mutations in each organism in each part of the lung. By comparing samples from multiple patients, they were then able to identify the key set of genes that enabled this organism to change into a potentially deadly pathogen.

These adaptations can occur very quickly, but the team found that their ability to transmit between patients was constrained: paradoxically, those mutations that allowed the organism to become a more successful pathogen within the patient also reduced its ability to survive on external surfaces and in the air - the key mechanisms by which it is thought to transmit between people.

Potentially one of the most important genetic changes witnessed by the team was one that contributed towards M. abscessus becoming resistant to nitric oxide, a compound naturally produced by the human immune system. The team will shortly begin a clinical trial aimed at boosting nitric oxide in patients' lung by using inhaled acidified nitrite, which they hope would become a novel treatment for the devastating infection.

Examining the DNA taken from patient samples is also important in helping understand routes of transmission. Such techniques are used routinely in Cambridge hospitals to map the spread of infections such as MRSA and C. difficile - and more recently, SARS-CoV-2. Insights into the spread of M. abscessus helped inform the design of the new Royal Papworth Hospital building, opened in 2019, which has a state-of-the-art ventilation system to prevent transmission. The team recently published a study showing that this ventilation system was highly effective at reducing the amount of bacteria in the air.

Professor Julian Parkhill, joint senior author from the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge, added: "M. abscessus can be a very challenging infection to treat and can be very dangerous to people living with cystic fibrosis, but we hope insights from our research will help us reduce the risk of transmission, stop the bug evolving further, and potentially prevent the emergence of new pathogenic variants."

The team have used their research to develop insights into the evolution of M. tuberculosis - the pathogen that causes TB about 5,000 years ago. In a similar way to M. abscessus, M. tuberculosis likely started life as an environmental organism, acquired genes by horizontal transfer that made particular clones more virulent, and then evolved through multiple rounds of within-host evolution. While M. abscessus is currently stopped at this evolutionary point, M. tuberculosis evolved further to be able to jump directly from one person to another.

Dr Lucy Allen, Director of Research at the Cystic Fibrosis Trust, said: "This exciting research brings real hope of better ways to treat lung infections that are resistant to other drugs. Our co-funded Innovation Hub with the University of Cambridge really shows the power of bringing together world-leading expertise to tackle a health priority identified by people with cystic fibrosis. We're expecting to see further impressive results in the future coming from our joint partnership."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Cystic Fibrosis Trust, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and The Botnar Foundation

Reference

Bryant, JM et al. Stepwise pathogenic evolution of Mycobacterium abscessus. Science; 30 Apr 2021

Considerable gap in evidence around whether portable air filters reduce the incidence of COVID-19 and other respiratory infections

There is an important absence of evidence regarding the effectiveness of a potentially cost-efficient intervention to prevent indoor transmission of respiratory infections, including COVID-19, warns a study by researchers at the University of Bristol.

Respiratory infections such as coughs, colds, and influenza, are common in all age groups, and can be either viral or bacterial. Bacteria and viruses can become airborne via talking, coughing or sneezing. The current global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is also spread primarily by airborne droplets, and to date has led to over three million deaths ...

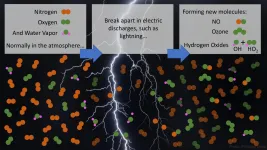

Lightning bolts break apart nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the atmosphere and create reactive chemicals that affect greenhouse gases. Now, a team of atmospheric chemists and lightning scientists have found that lightning bolts and, surprisingly, subvisible discharges that cannot be seen by cameras or the naked eye produce extreme amounts of the hydroxyl radical -- OH -- and hydroperoxyl radical -- HO2.

The hydroxyl radical is important in the atmosphere because it initiates chemical reactions and breaks down molecules like the greenhouse gas methane. OH is the main driver of many compositional changes in the atmosphere.

"Initially, we looked at these huge OH and HO2 signals found in the clouds and asked, what is wrong with our instrument?" said William ...

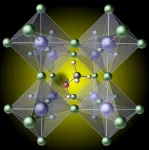

Researchers in the materials department in UC Santa Barbara's College of Engineering have uncovered a major cause of limitations to efficiency in a new generation of solar cells.

Various possible defects in the lattice of what are known as hybrid perovskites had previously been considered as the potential cause of such limitations, but it was assumed that the organic molecules (the components responsible for the "hybrid" moniker) would remain intact. Cutting-edge computations have now revealed that missing hydrogen atoms in these molecules can cause massive efficiency losses. The findings are published in ...

An international team led by Xiangming Xiao, George Lynn Cross Research Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Plant Biology, University of Oklahoma College of Arts and Sciences, published a paper in the April issue of the journal Nature Climate Change that has major implications on forest policies, conservation and management practices in the Brazilian Amazon. Xiao also is director of OU's Center for Earth Observation and Modeling. Yuanwei Qin, a research scientist at the Center for Earth Observation and Modeling, is the lead author of the study.

For the study described in the paper, "Carbon loss ...

As part of a laboratory experiment, Rebecca Holmes examined water bottles that had been acquired from abroad expecting to find bisphenol A (BPA), a human-made component commonly found in polycarbonate plastics used to make consumer products.

What she found, however, was that those water bottles were just fine, yet some control bottles purchased in the United States and supposedly BPA-free actually contained traces of the chemical now thought to negatively impact heart health.

Holmes, a researcher formerly in the laboratory of Hong-Sheng Wang, PhD, professor in the University of Cincinnati Department of Pharmacology and Systems Physiology, was working on her master's degree in molecular, cellular and biochemical ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. (APRIL 29, 2021) - Results from a new study find a broad range of patients who typically undergo revascularization for stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) in the U.S. did not meet enrollment criteria for the ISCHEMIA trial. The data, which was presented today as late-breaking clinical science at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions, demonstrates a minority of SIHD patients referred for coronary intervention in contemporary practice clearly resemble those enrolled in the ISCHEMIA trial.

Ischemic heart disease impacts more than 13 million people in the United States and is the leading cause ...

WASHINGTON, D.C, (April 29, 2021) - An analysis of growth patterns in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) programs across United States hospitals is being presented as late-breaking clinical science at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography& Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions. The findings indicate that TAVR hospital programs are predominately located in metropolitan areas serving patients with higher socioeconomic status, potentially contributing to the disparities in cardiac care.

TAVR is a minimally invasive procedure for patients in need of a valve repair or replacement and is an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), a treatment ...

Washington, D.C., April 29, 2021 - Two studies related to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) evaluating the use of risk-avoidance strategies and robotic-assisted technology, respectively, are being presented as late-breaking clinical science at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) 2021 Scientific Sessions. An analysis of strategically avoiding high-risk PCI cases indicates systematic risk-avoidance does not improve, and may worsen, the quality of hospital PCI programs. A study of a robotic-assisted PCI shows the technology is safe and effective for the treatment of both simple and complex lesions; this has the potential to address the occupational ...

The United Kingdom government plans to implement mass scale population testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection using Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs), yet the devices' sensitivity is unknown. A study published in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Alan McNally at University of Birmingham, UK, and colleagues suggests while LFDs are highly effective in identifying SARS-CoV-2 in individuals with high quantities of viral RNA present on the test swab, they are inaccurate at diagnosing infections in individuals with lower viral loads.

LFDs are increasingly used to increase testing capacity and screen asymptomatic populations for SARS-CoV-2 infection in mass surveillance programs, yet there are few data ...

Forget diamonds--plastic is forever. It takes decades, or even centuries, for plastic to break down, and nearly every piece of plastic ever made still exists in some form today. We've known for a while that big pieces of plastic can harm wildlife--think of seabirds stuck in plastic six-pack rings--but in more recent years, scientists have discovered microscopic bits of plastic in the water, soil, and even the atmosphere. To learn how these microplastics have built up over the past century, researchers examined the guts of freshwater fish preserved in museum collections; they found that fish have been swallowing microplastics since the 1950s and that the concentration of microplastics in their guts ...