(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

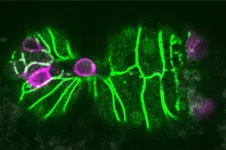

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that the same process can be driven by mammalian cells; they believe extrusion may serve as a way for the body to eliminate cancerous or precancerous cells.

"Cell extrusion is a mechanism of cell elimination used by organisms as diverse as sponges, insects, and humans," says H. Robert Horvitz, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology at MIT, a member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and the senior author of the study. "The discovery that extrusion is driven by a failure in DNA replication was unexpected and offers a new way to think about and possibly intervene in certain diseases, particularly cancer."

MIT postdoc Vivek Dwivedi is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature. Other authors of the paper are King's College London research fellow Carlos Pardo-Pastor, MIT research specialist Rita Droste, MIT postdoc Ji Na Kong, MIT graduate student Nolan Tucker, Novartis scientist and former MIT postdoc Daniel Denning, and King's College London professor of biology Jody Rosenblatt.

Stuck in the cell cycle

In the 1980s, Horvitz was one of the first scientists to analyze a type of programmed cell suicide called apoptosis, which organisms use to eliminate cells that are no longer needed. He made his discoveries using C. elegans, a tiny nematode that contains exactly 959 cells. The developmental lineage of each cell is known, and embryonic development follows the same pattern every time. Throughout this developmental process, 1,090 cells are generated, and 131 cells undergo programmed cell suicide by apoptosis.

Horvitz's lab later showed that if the worms were genetically mutated so that they could not eliminate cells by apoptosis, a few of those 131 cells would instead be eliminated by cell extrusion, which appears to be able to serve as a backup mechanism to apoptosis. How this extrusion process gets triggered, however, remained a mystery.

To unravel this mystery, Dwivedi performed a large-scale screen of more than 11,000 C. elegans genes. One by one, he and his colleagues knocked down the expression of each gene in worms that could not perform apoptosis. This screen allowed them to identify genes that are critical for turning on cell extrusion during development.

To the researchers' surprise, many of the genes that turned up as necessary for extrusion were involved in the cell division cycle. These genes were primarily active during first steps of the cell cycle, which involve initiating the cell division cycle and copying the cell's DNA.

Further experiments revealed that cells that are eventually extruded do initially enter the cell cycle and begin to replicate their DNA. However, they appear to get stuck in this phase, leading them to be extruded.

Most of the cells that end up getting extruded are unusually small, and are produced from an unequal cell division that results in one large daughter cell and one much smaller one. The researchers showed that if they interfered with the genes that control this process, so that the two daughter cells were closer to the same size, the cells that normally would have been extruded were able to successfully complete the cell cycle and were not extruded.

The researchers also showed that the failure of the very small cells to complete the cell cycle stems from a shortage of the proteins and DNA building blocks needed to copy DNA. Among other key proteins, the cells likely don't have enough of an enzyme called LRR-1, which is critical for DNA replication. When DNA replication stalls, proteins that are responsible for detecting replication stress quickly halt cell division by inactivating a protein called CDK1. CDK1 also controls cell adhesion, so the researchers hypothesize that when CDK1 is turned off, cells lose their stickiness and detach, leading to extrusion.

Cancer protection

Horvitz's lab then teamed up with researchers at King's College London, led by Rosenblatt, to investigate whether the same mechanism might be used by mammalian cells. In mammals, cell extrusion plays an important role in replacing the lining of the intestines, lungs, and other organs.

The researchers used a chemical called hydroxyurea to induce DNA replication stress in canine kidney cells grown in cell culture. The treatment quadrupled the rate of extrusion, and the researchers found that the extruded cells made it into the phase of the cell cycle where DNA is replicated before being extruded. They also showed that in mammalian cells, the well-known cancer suppressor p53 is involved in initiating extrusion of cells experiencing replication stress.

That suggests that in addition to its other cancer-protective roles, p53 may help to eliminate cancerous or precancerous cells by forcing them to extrude, Dwivedi says.

"Replication stress is one of the characteristic features of cells that are precancerous or cancerous. And what this finding suggests is that the extrusion of cells that are experiencing replication stress is potentially a tumor suppressor mechanism," he says.

The fact that cell extrusion is seen in so many animals, from sponges to mammals, led the researchers to hypothesize that it may have evolved as a very early form of cell elimination that was later supplanted by programmed cell suicide involving apoptosis.

"This cell elimination mechanism depends only on the cell cycle," Dwivedi says. "It doesn't require any specialized machinery like that needed for apoptosis to eliminate these cells, so what we've proposed is that this could be a primordial form of cell elimination. This means it may have been one of the first ways of cell elimination to come into existence, because it depends on the same process that an organism uses to generate many more cells."

INFORMATION:

Dwivedi, who earned his PhD at MIT, was a Khorana scholar before entering MIT for graduate school.

This research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institutes of Health.

What The Study Did: This study analyzed changes in Medicaid enrollment for all 50 states and the District of Columbia during the first nine months of last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Peggah Khorrami, M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9463)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Exeter scientists have discovered a simple, efficient way to recreate the early structure of the human embryo from stem cells in the laboratory. The new approach unlocks news ways of studying human fertility and reproduction.

Stem cells have the ability to turn into different types of cell. Now, in research published in Cell Stem Cell and funded by the Medical Research Council, scientists at the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, working with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, have developed a method to organise lab-grown stem cells into an accurate model of the first stage of human embryo development.

The ability to create artificial ...

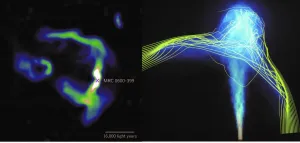

New observations and simulations show that jets of high-energy particles emitted from the central massive black hole in the brightest galaxy in galaxy clusters can be used to map the structure of invisible inter-cluster magnetic fields. These findings provide astronomers with a new tool for investigating previously unexplored aspects of clusters of galaxies.

As clusters of galaxies grow through collisions with surrounding matter, they create bow shocks and wakes in their dilute plasma. The plasma motion induced by these activities can drape intra-cluster magnetic ...

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL (University College London) have found that mice can sense extremely fast and subtle changes in the structure of odours and use this to guide their behaviour. The findings, published in Nature today (Wednesday), alter the current view on how odours are detected and processed in the mammalian brain.

Odour plumes, like the steam off a hot cup of coffee, are complex and often turbulent structures, and can convey meaningful information about an animal's surroundings, like the movements of a predator or the location of food sources. But it has previously been assumed that mammalian brains can't fully process these temporal ...

Chimpanzees and bonobos diverged comparatively recently in great ape evolutionary history. They split into different species about 1.7 million years ago. Some of the distinctions between chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus) lineages have been made clearer by a recent achievement in hominid genomics.

A new bonobo genome assembly has been constructed with a multiplatform approach and without relying on reference genomes. According to the researchers on this project, more than 98% of the genes are now completely annotated and 99% of the gaps are closed.

The ...

Graphene is a two-dimensional nanomaterial composed of carbon and formed by a single layer of densely packed carbon atoms. The high mechanical strength and significant electrical and thermal properties of graphene mean that it is highly suited to many new applications in the fields of electronics, biological, chemical and magnetic sensors, photodetectors and energy storage and generation. Due to its potential applications, graphene production is expected to increase significantly in the coming years, but given its low market uptake and the limitations in analysing its effects, little information on the concentrations of graphene nanomaterials in ecosystems ...

Loneliness and social isolation, which can have negative effects on health and longevity, are being exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. More than half of surveyed adults with cancer have been experiencing loneliness in recent months, according to a study published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Studies conducted before the pandemic reported that 32 percent to 47 percent of patients with cancer are lonely. In this latest survey, which was administered in late May 2020, 53 percent of 606 patients with a cancer diagnosis were categorized as experiencing loneliness. Patients in the lonely group reported higher levels of social isolation, as well as more severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, ...

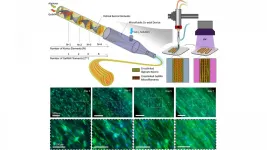

WASHINGTON, May 5, 2021 - 3D bioprinting can create engineered scaffolds that mimic natural tissue. Controlling the cellular organization within those engineered scaffolds for regenerative applications is a complex and challenging process.

Cell tissues tend to be highly ordered in terms of spatial distribution and alignment, so bioengineered cellular scaffolds for tissue engineering applications must closely resemble this orientation to be able to perform like natural tissue.

In Applied Physics Reviews, from AIP Publishing, an international research team describes its approach for directing cell orientation within ...

LAWRENCE -- Researchers at the University of Kansas have described a new species of fanged frog discovered in the Philippines that's nearly indistinguishable from a species on a neighboring island except for its unique mating call and key differences in its genome.

The KU-led team has just published its findings in the peer-reviewed journal Ichthyology & Herpetology.

"This is what we call a cryptic species because it was hiding in plain sight in front of biologists, for many, many years," said lead author Mark Herr, a doctoral student at the KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum ...

"The findings of our study tell us where and when greenhouse gas is being most absorbed in Arctic waters." Says Friederike Gründger, who conducted the study as part of her post-doctoral research at CAGE.

The study, which was conducted on the shallow shelf west of Svalbard, took a closer look at communities of bacteria that use methane as an energy source and carbon substrate for growth. The results from the study show that these methane-oxidizing bacteria are highly affected by the specific underwater landscape and seasonal conditions in the study area.

"Several large depressions, up to 40m deep, are observed along the shallow shelf off Western Svalbard, ...