(Press-News.org) Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

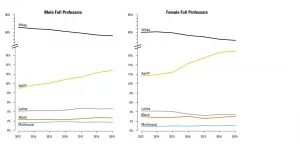

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits.

Women from these underrepresented groups were even more absent from leadership. During the study window, only one Black woman and one Latina woman ascended to the role of department chair, up from zero prior to 2015, suggesting that the combination of gender with race or ethnicity deepened the disadvantages these surgeons faced when trying to rise through the ranks.

"There are a lot of talented surgeons of different races, ethnicities and genders who do wonderful work and are being underrecognized or not recognized at all. And that's contributed to a lot of frustration," said study senior author Jose Trevino, M.D., chair of surgical oncology and associate professor of surgery at the VCU School of Medicine and surgeon-in-chief at VCU Massey Cancer Center.

In 2019, the vast majority of chairs and full professors were white, occupying about three quarters of these positions. Black and Latinx surgeons held about 3% to 5% of the full professorships and chairs -- clear underrepresentation considering the overall demographics of the country.

"I don't think it's a matter that they don't aspire to these positions," said study lead author Andrea Riner, M.D., M.P.H., a surgical resident at the University of Florida College of Medicine. "And I think many of them are truly qualified to lead."

Over the six-year study period, the share of surgery department chairs and full professorships held by white doctors decreased by 4 to 5 percentage points, but it was Asian faculty who filled the void, rising by 4 percentage points over the same timeframe.

Male Black and Latino chairs actually lost ground during the six-year study period, dropping 0.1 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively.

According to the authors, one way to promote success for traditionally underrepresented groups is sponsorship -- meaning someone in a position of power serves as an advocate for someone else who doesn't have the same level of influence.

"Having that person speak up for you and say you are deserving of whatever position you'd like to hold is really powerful," Riner said. "As a profession, we need to be a little more cognizant or intentional about sponsoring diverse people within our departments."

Mentorship and allyship are also important for leveling inequities in surgical leadership. Similar to sponsors, mentors provide expertise and support, though they may not have the clout to create opportunities for their mentees the way a sponsor could. Allyship is broader still. Anyone can be an ally, regardless of career level, so long as they lend support.

And the simple act of representation helps too. When students and residents see leaders who look like them, aspiring to those positions seems more realistic. But when female and minority trainees see a glass ceiling, they may be more likely to choose a different career.

"There are a lot of great leaders in surgery now -- leaders who are very much willing to address these inequities, though their day-to-day activities don't really allow for it," said Trevino, who also holds VCU's Walter E. Lawrence, Jr., Distinguished Professorship of Oncology. "Every now and again we as a profession need to take a pause and remind the people who are at the top of these academic ladders that they can help someone up and push them forward."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the study include Kelly Herremans, M.D., Daniel Neal, M.S., Crystal Johnson-Mann, M.D., Steven Hughes, M.D., and Gilbert Upchurch, M.D., of UF College of Medicine; and Kandace McGuire, M.D., of VCU Massey Cancer Center.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Human Genome Research Institute (grant T32 HG008958), the National Cancer Institute (grant R01CA242003) and the Joseph and Ann Matella Fund for Pancreatic Cancer Research.

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

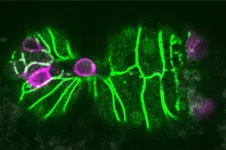

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that ...

What The Study Did: This study analyzed changes in Medicaid enrollment for all 50 states and the District of Columbia during the first nine months of last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Peggah Khorrami, M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9463)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Exeter scientists have discovered a simple, efficient way to recreate the early structure of the human embryo from stem cells in the laboratory. The new approach unlocks news ways of studying human fertility and reproduction.

Stem cells have the ability to turn into different types of cell. Now, in research published in Cell Stem Cell and funded by the Medical Research Council, scientists at the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, working with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, have developed a method to organise lab-grown stem cells into an accurate model of the first stage of human embryo development.

The ability to create artificial ...

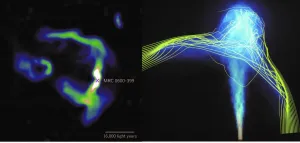

New observations and simulations show that jets of high-energy particles emitted from the central massive black hole in the brightest galaxy in galaxy clusters can be used to map the structure of invisible inter-cluster magnetic fields. These findings provide astronomers with a new tool for investigating previously unexplored aspects of clusters of galaxies.

As clusters of galaxies grow through collisions with surrounding matter, they create bow shocks and wakes in their dilute plasma. The plasma motion induced by these activities can drape intra-cluster magnetic ...

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL (University College London) have found that mice can sense extremely fast and subtle changes in the structure of odours and use this to guide their behaviour. The findings, published in Nature today (Wednesday), alter the current view on how odours are detected and processed in the mammalian brain.

Odour plumes, like the steam off a hot cup of coffee, are complex and often turbulent structures, and can convey meaningful information about an animal's surroundings, like the movements of a predator or the location of food sources. But it has previously been assumed that mammalian brains can't fully process these temporal ...

Chimpanzees and bonobos diverged comparatively recently in great ape evolutionary history. They split into different species about 1.7 million years ago. Some of the distinctions between chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus) lineages have been made clearer by a recent achievement in hominid genomics.

A new bonobo genome assembly has been constructed with a multiplatform approach and without relying on reference genomes. According to the researchers on this project, more than 98% of the genes are now completely annotated and 99% of the gaps are closed.

The ...

Graphene is a two-dimensional nanomaterial composed of carbon and formed by a single layer of densely packed carbon atoms. The high mechanical strength and significant electrical and thermal properties of graphene mean that it is highly suited to many new applications in the fields of electronics, biological, chemical and magnetic sensors, photodetectors and energy storage and generation. Due to its potential applications, graphene production is expected to increase significantly in the coming years, but given its low market uptake and the limitations in analysing its effects, little information on the concentrations of graphene nanomaterials in ecosystems ...

Loneliness and social isolation, which can have negative effects on health and longevity, are being exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. More than half of surveyed adults with cancer have been experiencing loneliness in recent months, according to a study published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Studies conducted before the pandemic reported that 32 percent to 47 percent of patients with cancer are lonely. In this latest survey, which was administered in late May 2020, 53 percent of 606 patients with a cancer diagnosis were categorized as experiencing loneliness. Patients in the lonely group reported higher levels of social isolation, as well as more severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, ...

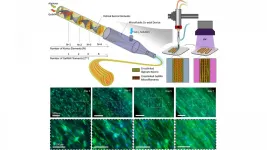

WASHINGTON, May 5, 2021 - 3D bioprinting can create engineered scaffolds that mimic natural tissue. Controlling the cellular organization within those engineered scaffolds for regenerative applications is a complex and challenging process.

Cell tissues tend to be highly ordered in terms of spatial distribution and alignment, so bioengineered cellular scaffolds for tissue engineering applications must closely resemble this orientation to be able to perform like natural tissue.

In Applied Physics Reviews, from AIP Publishing, an international research team describes its approach for directing cell orientation within ...

LAWRENCE -- Researchers at the University of Kansas have described a new species of fanged frog discovered in the Philippines that's nearly indistinguishable from a species on a neighboring island except for its unique mating call and key differences in its genome.

The KU-led team has just published its findings in the peer-reviewed journal Ichthyology & Herpetology.

"This is what we call a cryptic species because it was hiding in plain sight in front of biologists, for many, many years," said lead author Mark Herr, a doctoral student at the KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum ...