(Press-News.org) By discovering a potential new cellular mechanism for migraines, researchers may have also found a new way to treat chronic migraine.

Amynah Pradhan, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois Chicago, is the senior author of the study, whose goal was to identify a new mechanism of chronic migraine, and propose a cellular pathway for migraine therapies. The study, "Neuronal complexity is attenuated in preclinical models of migraine and restored by HDAC6 inhibition, is published in eLife.

Pradhan, whose research focus is on the neurobiology of pain and headache, explained that the dynamic process of routing and rerouting connections among nerve cells, called neural plasticity, is critical to both the causes and cures for disorders of the central nervous system such as depression, chronic pain, and addiction.

The structure of the cell is maintained by its cytoskeleton which is made up of the protein, tubulin. Tubulin is in a constant state of flux, waxing and waning to change the size and shape of the cell. This dynamic property of the cell allows the nervous system to change in response to its environment.

Tubulin is modified in the body through a chemical process called acetylation. When tubulin is acetylated it encourages flexible, stable cytoskeleton; while tubulin deacetylation - induced by histone deacetylase 6, or HDAC6, promotes cytoskeletal instability.

Studies in mice models show that decreased neuronal complexity may be a feature, or mechanism, of chronic migraine, Pradhan said. When HDAC6 is inhibited, tubulin acetylation and cytoskeletal flexibility is restored. Additionally, HDAC6 reversed the cellular correlates of migraine and relieved migraine-associated pain, according to the study.

"This work suggests that the chronic migraine state may be characterized by decreased neuronal complexity, and that restoration of this complexity could be a hallmark of anti-migraine treatments. This work also forms the basis for development of HDAC6 inhibitors as a novel therapeutic strategy for migraine," the researchers report.

Pradhan said this research reveals a way to possibly reset the brain toward its pre-chronic migraine state.

"Blocking HDAC6 would allow neurons to restore its flexibility so the brain would be more receptive to other types of treatment. In this model we are saying, maybe chronic migraine sufferers have decreased neuronal flexibility. If we can restore that complexity maybe we could get them out of that cycle," she said.

Once out of the cycle of decreased neuronal complexity, the brain may become more responsive to pain management therapies, Pradhan said. HDAC6 inhibitors are currently in development for cancer, and HDCA6 as a target has been identified for other types of pain.

"It opens up the possibility of something we should be looking at on a broader scale," she said. "Are these changes maybe a hallmark of all sorts of chronic pain states?"

Migraine is a common brain disorder that is estimated to affect 14% of the world population. Current U.S. cost estimates for migraine are as high as $40 billion annually. One particularly debilitating subset of migraine patients are those with chronic migraine, defined as having more than 15 headache days a month. Migraine therapies are often only partially effective or poorly tolerated, creating a need for more diverse drug therapies.

INFORMATION:

Pradhan and her research group collaborated with Dr. Mark Rasenick, distinguished professor of physiology and biophysics at UIC, and a research career scientist at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center.

Additional researchers are: Zachariah Bertels, Harinder Singh, Isaac Dripps, Kendra Siegersma, Alycia Tipton, Wiktor Witkowski, Zoie Sheets, Pal Shah, Catherine Conway, Elizaveta Mangutov, Mei Ao, Valentina Petukhova, Bhargava Karumudi, and Pavel Petukhov, all of UIC; and Serapio Baca of the University of Colorado.

Funding for this research includes grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS109862), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA040688), the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (AT009169), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Integrated Healthcare (BX00149), Amgen Foundation, and the UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

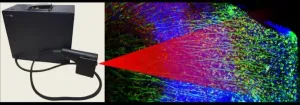

PHILADELPHIA-- It turns out that not all build-ups of tau protein are bad, and a team of researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania developed a method to show that. Using mammalian cell models, the researchers combined extremely high-resolution microscopy with machine learning to show that tau actually forms small aggregates when a part of the body's normal physiology. Through this, they could distinguish between the aggregates occurring under healthy conditions from the ones associated with neurological diseases, potentially opening the door to screening for treatments that ...

Scientists from Russia and Italy studied a new axis of the pathway that prevents the development of liver fibrosis. The role of GILZ protein in curbing the disease progression was shown in a study using mice models and confirmed by clinical data. These findings can be used in the treatment of liver fibrosis in humans. The research was published in the journal Cell Death & Disease.

Fibrosis combines an overgrowth of connective tissue and a decline in the liver function that can be caused by a viral infection, alcohol intoxication, autoimmune diseases or other liver disorders. If left untreated, fibrosis can lead to cirrhosis and even death. ...

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., May 5, 2021-- A massive collaborative research project covered in the journal Nature this week offers projections to the year 2100 of future sea-level rise from all sources of land ice, offering the most complete projections created to date.

"This work synthesizes improvements over the last decade in climate models, ice sheet and glacier models, and estimates of future greenhouse gas emissions," said Stephen Price, one of the Los Alamos scientists on the project. "More than 85 researchers from various disciplines, including our team at Los Alamos National Laboratory, produced sea-level rise projections based on the most recent ...

Sea ice cover in the Southern Hemisphere is extremely variable, from summer to winter and from millennium to millennium, according to a University of Maine-led study. Overall, sea ice has been on the rise for about 10,000 years, but with some exceptions to this trend.

Dominic Winski, a research assistant professor at the UMaine Climate Change Institute, spearheaded a project that uncovered new information about millennia of sea ice variability, particularly across seasons, in the Southern Hemisphere by examining the chemistry of a 54,000-year-old South Pole ice core.

The Southern Ocean experiences the largest seasonal ...

ARLINGTON, TX (May 5, 2021) -- Nanoscope Technologies LLC, a biotechnology company developing gene therapies for treatment of retinal diseases, is featuring multiple scientific presentations highlighting its groundbreaking research on optical gene delivery for vision restoration and OCT-guided electrophysiology platforms for characterization of retinal degeneration and assessment of efficacy of cell-gene therapy at the 2021 ARVO annual (virtual) meeting, May 1-7.

ARVO, the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, is the largest eye and vision research organization in the world with nearly 11,000 members in more than 75 countries.

Nanoscope's lead product is an optogenetic ...

Increased access to birth control led to higher graduation rates among young women in Colorado, according to a study following the debut of the 2009 Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CPFI). The study identified a statistically significant 1.66 percentage-point increase in high school graduation among young women one year after the initiative was introduced. The findings provide concrete evidence for the rationale behind the U.S. Title X program, which calls for access to reproductive health services for low-income and uninsured residents, in part to help ensure women's ability to complete their education. However, at a time when funding for family planning programs is debated, robust scientific evidence to support this claim has been lacking. To investigate the link between access ...

Methane, a chemical compound with the molecular formula CH4, is not only a powerful greenhouse gas, but also an important energy source. It heats our homes, and even seafloor microbes make a living of it. The microbes use a process called anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM), which happens commonly in the seafloor in so-called sulfate-methane transition zones - layers in the seafloor where sulfate from the seawater meets methane from the deeper sediment. Here, specialized microorganisms, the ANaerobically MEthane-oxidizing (ANME) archaea, consume the methane. They live in close association with bacteria, which use electrons ...

Who made more accurate predictions about the course of the COVID-19 pandemic - experts or the public? A study from the University of Cambridge has found that experts such as epidemiologists and statisticians made far more accurate predictions than the public, but both groups substantially underestimated the true extent of the pandemic.

Researchers from the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication surveyed 140 UK experts and 2,086 UK laypersons in April 2020 and asked them to make four quantitative predictions about the impact of COVID-19 by the end of 2020. Participants were also asked to indicate confidence in their predictions by providing upper and lower bounds of where they were 75% sure that the true answer would fall - for example, ...

When access to free and low-cost birth control goes up, the percentage of young women who leave high school before graduating goes down by double-digits, according to a new CU Boulder-led study published May 5 in the journal Science Advances.

The study, which followed more than 170,000 women for up to seven years, provides some of the strongest evidence yet that access to contraception yields long-term socioeconomic benefits for women. It comes at a time when public funding for birth control is undergoing heated debate, and some states are considering banning certain forms.

"One of the foundational ...

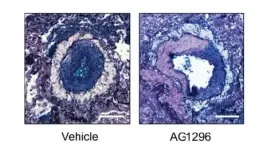

One of the dangerous health conditions that can occur among premature newborns, children born with heart defects, and some others is pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Commonly mistaken for asthma, this condition occurs when blood vessels in the lungs develop excessive resistance to blood flow. This forces the heart's right ventricle to work harder, causing it to enlarge, thicken and further elevate blood pressure. While early treatment usually succeeds, the condition can become persistent and progressive, which can lead to heart failure and death.

The exact incidence and prevalence of PAH remains unclear, but reviews of patient registries in Europe have estimated that the condition occurs in nearly 64 of every 1 million children, including transient cases. ...