(Press-News.org) Proteins are the workhorses of cells, responsible for almost all biological functions that make life possible.

Understanding how specific proteins work is key to disease prevention and treatment, allowing us to lead longer, healthier lives.

Yet scientists still know nothing or very little about thousands of proteins that exist in our bodies and their role in keeping us alive.

Now researchers from Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University have uncovered a new protein analysis tool - coined the Bacterial Growth Inhibition Screen (BGIS) - that could fast-track the process of assessing proteins. The tool allows for quick and efficient basic characterisation of protein function with no special equipment or cost involved.

Dr Ferdinand Kappes of XJTLU's Department of Biological Sciences says while it won't replace more complex and established protein analysis methods, the BGIS tool offers a viable 'pre-screening' method that could save scientists significant time in the lab, in turn accelerating basic science and medical discoveries.

"Many proteins have multiple 'business areas', and finding out these different functions and how they are regulated is essential to understanding how biological processes work," he says.

"Identifying and then manipulating the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, for example, was crucial in the development of a Covid-19 vaccine.

"We know misfunction or mis-regulation of proteins often results in diseases, but a large portion of human proteins still remain a mystery to us.

"One of the main reasons for this is that proteins are often difficult to study, as each new protein is like exploring a foreign city without a map for the first time - there are often no similar proteins to offer clues or even a starting point.

"The work is time-consuming, and results can be hard to come by, so many researchers avoid studying unknown proteins altogether.

"The tool we have developed provides researchers with a 'compass' of sorts. It allows them to quickly work out if they are on the right path by determining whether a protein has a function worth exploring."

The new tool could substantially facilitate the study of many proteins, according to Dr Kappes, and makes use of an unpopular side effect common in biology labs.

"Our tool uses recombinant protein toxicity, a well-known effect that happens when bacteria are used for the production of human proteins, such as insulin for medication," he says.

"Essentially, we force the bacteria to produce a foreign protein, but this often interferes with the natural biology of the bacteria and causes a number of stress scenarios.

"As we usually only use bacteria as a surrogate for protein production - the negative 'stress scenarios' on the bacteria are considered a burden and are typically not looked at further.

"What we have highlighted is that these negative effects can be harnessed and used as an easy way to gain fundamental functional information by seeing how the bacteria responds to the expression of foreign proteins.

"If bacteria growth is affected by the foreign protein, we know there is some sort of function coded in the protein that warrants further investigation. The BGIS also allows for quick manipulation of the protein at hand exploring the same principle.

"After our initial discovery, we applied this technique to every protein we could find in our labs. It worked every time. It really is like turning lemons into lemonade - it's a byproduct of biological experiments researchers dreaded, but we've been able to turn into a tool to aid discovery.

"In addition, the BGIS allowed us to substantially advance our own research on the oncoprotein DEK, which is a longstanding interest in our own laboratory."

INFORMATION:

The research findings have been published back-to-back in two papers, titled 'Bacterial Growth Inhibition Screen (BGIS): harnessing recombinant protein toxicity for rapid and unbiased interrogation of protein function' and 'Bacterial Growth Inhibition Screen (BGIS) identifies a loss of function mutant of the DEK oncogene, indicating DNA modulating activities of DEK in chromatin' in FEBS Letters.

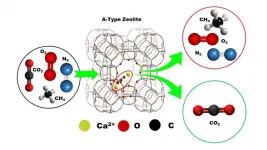

It is now well known that carbon dioxide is the biggest contributor to climate change and originates primarily from burning of fossil fuels. While there are ongoing efforts around the world to end our dependence on fossil fuels as energy sources, the promise of green energy still lies in the future. Can something be done in the meantime to reduce the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere?

It would, in fact, be great if the CO2 in the atmosphere could simply be adsorbed! Turns out, this is exactly what direct air capture (DAC), or the capture of CO2 under ambient conditions, aims to do. However, no such material with the ability to adsorb CO2 efficiently under DAC ...

In Alzheimer's disease, neurons in the brain die. Largely responsible for the death of neurons are certain protein deposits in the brains of affected individuals: So-called beta-amyloid proteins, which form clumps (plaques) between neurons, and tau proteins, which stick together the inside of neurons. The causes of these deposits are as yet unclear. In addition, a rapidly progressive atrophy, i.e. a shrinking of the brain volume, can be observed in affected persons. Alzheimer's symptoms such as memory loss, disorientation, agitation and challenging behavior are the consequences.

Scientists at the DZNE led by Prof. Michael Wagner, head of a research group at the DZNE and senior ...

Determining safe yet effective drug dosages for children is an ongoing challenge for pharmaceutical companies and medical doctors alike. A new drug is usually first tested on adults, and results from these trials are used to select doses for pediatric trials. The underlying assumption is typically that children are like adults, just smaller, which often holds true, but may also overlook differences that arise from the fact that children's organs are still developing.

Compounding the problem, pediatric trials don't always shed light on other differences that can affect recommendations for drug doses. There are many factors that limit children's participation in drug trials - for instance, some diseases simply ...

AURORA, Colo. (May 6, 2021) - Scientists examining the remains of 36 bubonic plague victims from a 16th century mass grave in Germany have found the first evidence that evolutionary adaptive processes, driven by the disease, may have conferred immunity on later generations of people from the region.

"We found that innate immune markers increased in frequency in modern people from the town compared to plague victims," said the study's joint-senior author Paul Norman, PhD, associate professor in the Division of Personalized Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "This suggests these markers might have evolved to resist the plague."

The study, done in conjunction with the Max Planck Institute in Germany, was published online Thursday in the journal Molecular ...

Ultrasound is an indispensable tool for the life sciences and various industrial applications due to its non-destructive, high contrast, and high resolution qualities. A persistent challenge over the years has been how to increase the resolution of an acoustic endoscope without drastically increasing the footprint of the probe, or risking the robustness of the ultrasonic transducer. In recent years, a host of all-optical ultrasonic imaging techniques have emerged - which generally utilise pulsed lasers and optical cavities to excite and detect ultrasound waves - without sacrificing device footprint, sensitivity, or the integrity of the transducer. Thus far these powerful techniques have achieved imaging resolutions on microscopic-mesoscopic length ...

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have discovered previously unknown non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) involved in regulating the gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), the master regulators of angiogenesis. The study, conducted by the research groups of Associate Professor Minna Kaikkonen-Määttä and Academy Professor Seppo Ylä-Herttuala, provides a better understanding of the complex interplay of ncRNAs with gene regulation, which might open up novel therapeutic approaches in the future. The results were published in the Molecular and Cellular Biology Journal.

Over the past years, the development of next generation ...

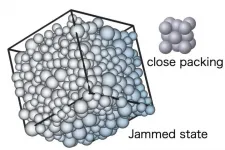

Researchers at Chinese Academy of Science and Osaka University show that, unlike the crystalline close packing of spheres, random close packing or jamming of spheres in a container can take place in a broad range of densities and anisotropies. Furthermore, they show that such diverse jammed states are all just marginally stable and exhibit common universal critical properties.

Osaka, Japan - Scientists at the theoretical institutes, Chinese Academy of Science and Cybermedia Center at Osaka University performed extensive computer simulations to generate and examine random packing of spheres. They show that the "jamming" ...

A KAIST research team has developed a new technology that enables to process a large-scale graph algorithm without storing the graph in the main memory or on disks. Named as T-GPS (Trillion-scale Graph Processing Simulation) by the developer Professor Min-Soo Kim from the School of Computing at KAIST, it can process a graph with one trillion edges using a single computer.

Graphs are widely used to represent and analyze real-world objects in many domains such as social networks, business intelligence, biology, and neuroscience. As the number of graph applications increases rapidly, developing and testing new graph algorithms is becoming more important than ever before. Nowadays, many industrial ...

Trust, safety and security are the most important factors affecting passengers' attitudes towards self-driving cars. Younger people felt their personal security to be significantly better than older people.

The findings are from a Finnish study into passengers' attitudes towards, and experiences of, self-driving cars. The study is also the first in the world to examine passengers' experiences of self-driving cars in winter conditions.

The findings were published in Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. The study was carried out in collaboration between the University of Eastern Finland and Tampere University.

Self-driving cars face huge expectations in Europe and the United States, which is why passengers' ...

A new study has shown that most patients discharged from hospital after experiencing severe COVID-19 infection appear to return to full health, although up to a third do still have evidence of effects upon the lungs one year on.

COVID-19 has infected millions of people worldwide. People are most commonly hospitalised for COVID-19 infection when it affects the lungs - termed COVID-19 pneumonia. Whilst significant progress has been made in understanding and treating acute COVID-19 pneumonia, very little is understood about how long it takes for patients to fully recover and whether changes within the lungs persist.

In this new study, published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, researchers from the University of Southampton worked with collaborators ...