(Press-News.org) For millennia, humans in the high latitudes have been enthralled by auroras--the northern and southern lights. Yet even after all that time, it appears the ethereal, dancing ribbons of light above Earth still hold some secrets.

In a new study, physicists led by the University of Iowa report a new feature to Earth's atmospheric light show. Examining video taken nearly two decades ago, the researchers describe multiple instances where a section of the diffuse aurora--the faint, background-like glow accompanying the more vivid light commonly associated with auroras--goes dark, as if scrubbed by a giant blotter. Then, after a short period of time, the blacked-out section suddenly reappears.

The researchers say the behavior, which they call "diffuse auroral erasers," has never been mentioned in the scientific literature. The findings appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research Space Physics.

Auroras occur when charged particles flowing from the sun--called the solar wind--interact with Earth's protective magnetic bubble. Some of those particles escape and fall toward our planet, and the energy released during their collisions with gases in Earth's atmosphere generate the light associated with auroras.

"The biggest thing about these erasers that we didn't know before but know now is that they exist," says Allison Jaynes, assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Iowa and study co-author. "It raises the question: Are these a common phenomenon that has been overlooked, or are they rare?

"Knowing they exist means there is a process that is creating them," Jaynes continues, "and it may be a process that we haven't started to look at yet because we never knew they were happening until now."

It was on March 15, 2002, that David Knudsen, a physicist at the University of Calgary, set up a video camera in Churchill, a town along Hudson Bay in Canada, to film auroras. Knudsen's group was a little disheartened; the forecast called for clear, dark skies--normally perfect conditions for viewing auroras--but no dazzling illumination was happening. Still, the team was using a camera specially designed to capture low-level light, much like night-vision goggles.

Though the scientists saw only mostly darkness as they gazed upward with their own eyes, the camera was picking up all sorts of auroral activity, including an unusual sequence where areas of the diffuse aurora disappeared, then came back.

Knudsen, looking at the video as it was being recorded, scribbled in his notebook, "pulsating 'black out' diffuse glow, which then fills in over several seconds."

"What surprised me, and what made me write it in the notebook, is when a patch brightened and turned off, the background diffuse aurora was erased. It went away," says Knudsen, a Fort Dodge, Iowa, native who has studied aurora for more than 35 years and is a co-author on the study. "There was a hole in the diffuse aurora. And then that hole would fill back in after a half-minute or so. I had never seen something like that before."

The note lay dormant, and the video unstudied, until Iowa's Jaynes handed it to graduate student Riley Troyer to investigate. Jaynes learned about Knudsen's recording at a scientific meeting in 2010 and referenced the eraser note in her doctoral thesis on diffuse aurora a few years later. Now on the faculty at Iowa, she wanted to learn more about the phenomenon.

"I knew there was something there. I knew it was different and unique," says Jaynes, assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy. "l had some ideas how it could be analyzed, but I hadn't done that yet. I handed it to Riley, and he went much further with it by figuring out his own way to analyze the data and produce some significant conclusions."

Troyer, from Fairbanks, Alaska, took up the assignment with gusto.

"I've seen hundreds of auroras growing up," says Troyer, who is in his third year of doctoral studies at Iowa. "They're part of my heritage, something I can study while keeping ties to where I'm from."

Troyer created a software program to key in on frames in the video when the faint erasers were visible. In all, he cataloged 22 eraser events in the two-hour recording.

"The most valuable thing we found is showing the time that it takes for the aurora to go from an eraser event (when the diffuse aurora is blotted out) to be filled or colored again," says Troyer, who is the paper's corresponding author, "and how long it takes to go from that erased state back to being diffuse aurora. Having a value on that will help with future modeling of magnetic fields."

Jaynes says learning about diffuse auroral erasers is akin to studying DNA to understand the entire human body.

"Particles that fall into our atmosphere from space can affect our atmospheric layers and our climate," Jaynes says. "While particles with diffuse aurora may not be the main cause, they are smaller building blocks that can help us understand the aurora system as a whole, and may broaden our understanding how auroras happen on other planets in our solar system."

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors are Sarah Jones, from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and who was part of Knudsen's team in Churchill, and Trond Trondsen, with Keo Scientific Ltd., who built the camera that filmed the diffuse aurora.

NASA supported the data analysis.

New research published in Experimental Physiology highlight the possible long term health impacts of COVID-19 on young, relatively healthy adults who were not hospitalized and who only had minor symptoms due to the virus.

Increased stiffness of arteries in particular was found in young adults, which may impact heart health, and can also be important for other populations who may have had severe cases of the virus. This means that young, healthy adults with mild COVID-19 symptoms may increase their risk of cardiovascular complications which may continue for some time after COVID-19 infection.

While SARS-CoV-2, the virus known ...

Just as people keep their houses clean and clutter under control, a crew of cells in the body is in charge of clearing the waste the body generates, including dying cells. The housekeeping cells remove unwanted material by a process called phagocytosis, which literally means 'eating cells.' The housekeepers engulf and ingest the dying cells and break them down to effectively eliminate them.

"Phagocytosis is very important for the body's health," said Dr. Zheng Zhou, whose lab at Baylor College of Medicine has been studying phagocytosis for many years and provided key new insights into this essential process. "When this cell-eat-cell process fails, the dying cells will lose their integrity, break down and release their content into the surrounding tissues. Dumping the ...

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have developed an integrated, high-throughput system to better understand and possibly manipulate gene expression for treatment of disorders such as sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia. The research appears today in the journal Nature Genetics.

Researchers used the system to identify dozens of DNA regulatory elements that act together to orchestrate the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin expression. The method can also be used to study other diseases that involve gene regulation.

Regulatory elements, also called genetic switches, are scattered throughout non-coding regions of DNA. ...

Retinoblastoma starts in the retina, the thin membrane at the back of the eye. Most patients are infants or toddlers when their cancer is found. Without treatment, the cancer spreads. Thanks to chemotherapy, surgery and other treatments, 96% of patients survive.

St. Jude researchers studied how survivors fared years later at home and at school. A previous St. Jude study of 98 retinoblastoma survivors found that their early learning and life skills declined from diagnosis to age 5.

Researchers tested 78 of the same survivors five years later. The results were more upbeat. By age 10, almost all the children functioned within the normal range ...

Asthma attacks account for almost 50 percent of the cost of asthma care which totals $80 billion each year in the United States. Asthma is more severe in Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients, with double the rates of attacks and hospitalizations as the general population.

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the United States, a series of reports suggested that fewer people were coming to emergency departments for all sorts of medical problems, including asthma attacks and even heart attacks. In the case of asthma, it was not clear if the drop was due to people avoiding emergency services or due to better asthma control. A new analysis from investigators at Brigham and Women's Hospital shines new light on this question. In a report of ...

Vaccination dramatically reduced COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in St. Jude Children's Research Hospital employees compared with their unvaccinated peers, according to a research letter that appears today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study is among the first to show an association between COVID-19 vaccination and fewer asymptomatic infections. When the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine was authorized for use in the U.S., the vaccine was reported to be highly effective at preventing laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. Clinical trial data suggested that the two-dose regimen ...

New research combines cutting-edge engineering with animal behaviour to explain the origins of efficient swimming in Nature's underwater acrobats: Seals and Sea Lions.

Seals and sea lions are fast swimming ocean predators that use their flippers to literally fly through the water. But not all seals are the same: some swim with their front flippers while others propel themselves with their back feet.

In Australia, we have fur seals and sea lions that have wing-like front flippers specialised for swimming, while in the Northern Hemisphere, grey and harbor seals have stubby, clawed paws and swim with their feet. But the reasons ...

Sea turtles are known for relying on magnetic signatures to find their way across thousands of miles to the very beaches where they hatched. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on May 6 have some of the first solid evidence that sharks also rely on magnetic fields for their long-distance forays across the sea.

"It had been unresolved how sharks managed to successfully navigate during migration to targeted locations," said Save Our Seas Foundation project leader Bryan Keller, also of Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory. "This research supports the theory that they use the earth's magnetic field to help them find their way; it's nature's GPS."

Researchers ...

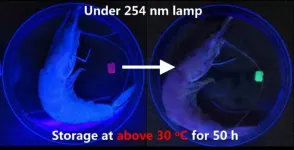

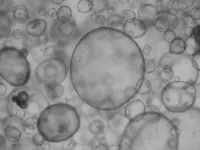

Scientists in China and Germany have designed an artificial color-changing material that mimics chameleon skin, with luminogens (molecules that make crystals glow) organized into different core and shell hydrogel layers instead of one uniform matrix. The findings, published May 6 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science, demonstrate that a two-luminogen hydrogel chemosensor developed with this design can detect seafood freshness by changing color in response to amine vapors released by microbes as fish spoils. The material may also be used to advance the development of stretchable electronics, dynamic camouflaging robots, and anticounterfeiting technologies.

"This novel core-shell layout does not require a careful choice of luminogen pairs, nor does it require an ...

Mini-organs or organoids play a big role in the future of medicine. Their countless applications can help develop and implement tailored therapies for each patient. The revolutionary development of organoids started in Utrecht with a group of curious scientists. But when organoid research starting booming, confusion arose. What exactly is an organoid? Are there different types, and if so, what should they be called? A group of experts from around the world now publishes the first consensus on what is - and what is not - an organoid.

Bart Spee, Associate Professor at Utrecht University's faculty of Veterinary Medicine, is ...