INFORMATION:

This research was supported, in part, by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Young Investigator Program and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. This research used resources of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials and National Synchrotron Light Source II, both U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facilities located at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Physicists find a novel way to switch antiferromagnetism on and off

The findings could lead to faster, more secure memory storage, in the form of antiferromagnetic bits

2021-05-06

(Press-News.org) When you save an image to your smartphone, those data are written onto tiny transistors that are electrically switched on or off in a pattern of "bits" to represent and encode that image. Most transistors today are made from silicon, an element that scientists have managed to switch at ever-smaller scales, enabling billions of bits, and therefore large libraries of images and other files, to be packed onto a single memory chip.

But growing demand for data, and the means to store them, is driving scientists to search beyond silicon for materials that can push memory devices to higher densities, speeds, and security.

Now MIT physicists have shown preliminary evidence that data might be stored as faster, denser, and more secure bits made from antiferromagnets.

Antiferromagnetic, or AFM materials are the lesser-known cousins to ferromagnets, or conventional magnetic materials. Where the electrons in ferromagnets spin in synchrony -- a property that allows a compass needle to point north, collectively following the Earth's magnetic field -- electrons in an antiferromagnet prefer the opposite spin to their neighbor, in an "antialignment" that effectively quenches magnetization even at the smallest scales.

The absence of net magnetization in an antiferromagnet makes it impervious to any external magnetic field. If they were made into memory devices, antiferromagnetic bits could protect any encoded data from being magnetically erased. They could also be made into smaller transistors and packed in greater numbers per chip than traditional silicon.

Now the MIT team has found that by doping extra electrons into an antiferromagnetic material, they can turn its collective antialigned arrangement on and off, in a controllable way. They found this magnetic transition is reversible, and sufficiently sharp, similar to switching a transistor's state from 0 to 1. The results, published today in Physical Review Letters, demonstrate a potential new pathway to use antiferromagnets as a digital switch.

"An AFM memory could enable scaling up the data storage capacity of current devices -- same volume, but more data," says the study's lead author Riccardo Comin, assistant professor of physics at MIT.

Comin's MIT co-authors include lead author and graduate student Jiarui Li, along with Zhihai Zhu, Grace Zhang, and Da Zhou; as well as Roberg Green of the University of Saskatchewan; Zhen Zhang, Yifei Sun, and Shriram Ramanathan of Purdue University; Ronny Sutarto and Feizhou He of Canadian Light Source; and Jerzy Sadowski at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Magnetic memory

To improve data storage, some researchers are looking to MRAM, or magnetoresistive RAM, a type of memory system that stores data as bits made from conventional magnetic materials. In principle, an MRAM device would be patterned with billions of magnetic bits. To encode data, the direction of a local magnetic domain within the device is flipped, similar to switching a transistor from 0 to 1.

MRAM systems could potentially read and write data faster than silicon-based devices and could run with less power. But they could also be vulnerable to external magnetic fields.

"The system as a whole follows a magnetic field like a sunflower follows the sun, which is why, if you take a magnetic data storage device and put it in a moderate magnetic field, information is completely erased," Comin says.

Antiferromagnets, in contrast, are unaffected by external fields and could therefore be a more secure alternative to MRAM designs. An essential step toward encodable AFM bits is the ability to switch antiferromagnetism on and off. Researchers have found various ways to accomplish this, mostly by using electric current to switch a material from its orderly antialignment, to a random disorder of spins.

"With these approaches, switching is very fast," says Li. "But the downside is, everytime you need a current to read or write, that requires a lot of energy per operation. When things get very small, the energy and heat generated by running currents are significant."

Doped disorder

Comin and his colleagues wondered whether they could achieve antiferromagnetic switching in a more efficient manner. In their new study, they work with neodymium nickelate, an antiferromagnetic oxide grown in the Ramanathan lab. This material exhibits nanodomains that consist of nickel atoms with an opposite spin to that of its neighbor, and held together by oxygen and neodymium atoms. The researchers had previously mapped the material's fractal properties.

Since then, the researchers have looked to see if they could manipulate the material's antiferromagnetism via doping -- a process that intentionally introduces impurities in a material to alter its electronic properties. In their case, the researchers doped neodymium nickel oxide by stripping the material of its oxygen atoms.

When an oxygen atom is removed, it leaves behind two electrons, which are redistributed among the other nickel and oxygen atoms. The researchers wondered whether stripping away many oxygen atoms would result in a domino effect of disorder that would switch off the material's orderly antialignment.

To test their theory, they grew 100-nanometer-thin films of neodymium nickel oxide and placed them in an oxygen-starved chamber, then heated the samples to temperatures of 400 degrees Celsius to encourage oxygen to escape from the films and into the chamber's atmosphere.

As they removed progressively more oxygen, they studied the films using advanced magnetic X-ray crystallography techniques to determine whether the material's magnetic structure was intact, implying that its atomic spins remained in their orderly antialignment, and therefore retained antiferomagnetism. If their data showed a lack of an ordered magnetic structure, it would be evidence that the material's antiferromagnetism had switched off, due to sufficient doping.

Through their experiments, the researchers were able to switch off the material's antiferromagnetism at a certain critical doping threshold. They could also restore antiferromagnetism by adding oxygen back into the material.

Now that the team has shown doping effectively switches AFM on and off, scientists might use more practical ways to dope similar materials. For instance, silicon-based transistors are switched using voltage-activated "gates," where a small voltage is applied to a bit to alter its electrical conductivity. Comin says that antiferromagnetic bits could also be switched using suitable voltage gates, which would require less energy than other antiferromagnetic switching techniques.

"This could present an opportunity to develop a magnetic memory storage device that works similarly to silicon-based chips, with the added benefit that you can store information in AFM domains that are very robust and can be packed at high densities," Comin says. "That's key to addressing the challenges of a data-driven world."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Physicists describe new type of aurora

2021-05-06

For millennia, humans in the high latitudes have been enthralled by auroras--the northern and southern lights. Yet even after all that time, it appears the ethereal, dancing ribbons of light above Earth still hold some secrets.

In a new study, physicists led by the University of Iowa report a new feature to Earth's atmospheric light show. Examining video taken nearly two decades ago, the researchers describe multiple instances where a section of the diffuse aurora--the faint, background-like glow accompanying the more vivid light commonly associated with auroras--goes dark, as if scrubbed by a giant blotter. Then, after a short period of time, the blacked-out section suddenly reappears.

The researchers say the behavior, which they call "diffuse ...

Healthy young adults who had COVID-19 may have long-term impact on blood vessels and heart health

2021-05-06

New research published in Experimental Physiology highlight the possible long term health impacts of COVID-19 on young, relatively healthy adults who were not hospitalized and who only had minor symptoms due to the virus.

Increased stiffness of arteries in particular was found in young adults, which may impact heart health, and can also be important for other populations who may have had severe cases of the virus. This means that young, healthy adults with mild COVID-19 symptoms may increase their risk of cardiovascular complications which may continue for some time after COVID-19 infection.

While SARS-CoV-2, the virus known ...

In a cell-eat-cell world calcium ions activate 'eat-me' signal in necrotic cells

2021-05-06

Just as people keep their houses clean and clutter under control, a crew of cells in the body is in charge of clearing the waste the body generates, including dying cells. The housekeeping cells remove unwanted material by a process called phagocytosis, which literally means 'eating cells.' The housekeepers engulf and ingest the dying cells and break them down to effectively eliminate them.

"Phagocytosis is very important for the body's health," said Dr. Zheng Zhou, whose lab at Baylor College of Medicine has been studying phagocytosis for many years and provided key new insights into this essential process. "When this cell-eat-cell process fails, the dying cells will lose their integrity, break down and release their content into the surrounding tissues. Dumping the ...

Researchers speed identification of DNA regions that regulate gene expression

2021-05-06

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have developed an integrated, high-throughput system to better understand and possibly manipulate gene expression for treatment of disorders such as sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia. The research appears today in the journal Nature Genetics.

Researchers used the system to identify dozens of DNA regulatory elements that act together to orchestrate the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin expression. The method can also be used to study other diseases that involve gene regulation.

Regulatory elements, also called genetic switches, are scattered throughout non-coding regions of DNA. ...

By age 10, retinoblastoma patients' learning and life skills rebound

2021-05-06

Retinoblastoma starts in the retina, the thin membrane at the back of the eye. Most patients are infants or toddlers when their cancer is found. Without treatment, the cancer spreads. Thanks to chemotherapy, surgery and other treatments, 96% of patients survive.

St. Jude researchers studied how survivors fared years later at home and at school. A previous St. Jude study of 98 retinoblastoma survivors found that their early learning and life skills declined from diagnosis to age 5.

Researchers tested 78 of the same survivors five years later. The results were more upbeat. By age 10, almost all the children functioned within the normal range ...

Asthma attacks plummeted among Black and hispanic/latinx individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic

2021-05-06

Asthma attacks account for almost 50 percent of the cost of asthma care which totals $80 billion each year in the United States. Asthma is more severe in Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients, with double the rates of attacks and hospitalizations as the general population.

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the United States, a series of reports suggested that fewer people were coming to emergency departments for all sorts of medical problems, including asthma attacks and even heart attacks. In the case of asthma, it was not clear if the drop was due to people avoiding emergency services or due to better asthma control. A new analysis from investigators at Brigham and Women's Hospital shines new light on this question. In a report of ...

COVID-19 vaccine is associated with fewer asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections

2021-05-06

Vaccination dramatically reduced COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in St. Jude Children's Research Hospital employees compared with their unvaccinated peers, according to a research letter that appears today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study is among the first to show an association between COVID-19 vaccination and fewer asymptomatic infections. When the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine was authorized for use in the U.S., the vaccine was reported to be highly effective at preventing laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. Clinical trial data suggested that the two-dose regimen ...

Engineers and biologists join forces to reveal how seals evolved to swim

2021-05-06

New research combines cutting-edge engineering with animal behaviour to explain the origins of efficient swimming in Nature's underwater acrobats: Seals and Sea Lions.

Seals and sea lions are fast swimming ocean predators that use their flippers to literally fly through the water. But not all seals are the same: some swim with their front flippers while others propel themselves with their back feet.

In Australia, we have fur seals and sea lions that have wing-like front flippers specialised for swimming, while in the Northern Hemisphere, grey and harbor seals have stubby, clawed paws and swim with their feet. But the reasons ...

Sharks use Earth's magnetic fields to guide them like a map

2021-05-06

Sea turtles are known for relying on magnetic signatures to find their way across thousands of miles to the very beaches where they hatched. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on May 6 have some of the first solid evidence that sharks also rely on magnetic fields for their long-distance forays across the sea.

"It had been unresolved how sharks managed to successfully navigate during migration to targeted locations," said Save Our Seas Foundation project leader Bryan Keller, also of Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory. "This research supports the theory that they use the earth's magnetic field to help them find their way; it's nature's GPS."

Researchers ...

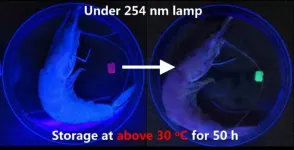

Artificial color-changing material that mimics chameleon skin can detect seafood freshness

2021-05-06

Scientists in China and Germany have designed an artificial color-changing material that mimics chameleon skin, with luminogens (molecules that make crystals glow) organized into different core and shell hydrogel layers instead of one uniform matrix. The findings, published May 6 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science, demonstrate that a two-luminogen hydrogel chemosensor developed with this design can detect seafood freshness by changing color in response to amine vapors released by microbes as fish spoils. The material may also be used to advance the development of stretchable electronics, dynamic camouflaging robots, and anticounterfeiting technologies.

"This novel core-shell layout does not require a careful choice of luminogen pairs, nor does it require an ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] Physicists find a novel way to switch antiferromagnetism on and offThe findings could lead to faster, more secure memory storage, in the form of antiferromagnetic bits