(Press-News.org) New Haven, Conn. -- If paleontologists had a wish list, it would almost certainly include insights into two particular phenomena: how dinosaurs interacted with each other and how they began to fly.

The problem is, using fossils to deduce such behavior is a tricky business. But a new, Yale-led study offers a promising entry point -- the inner ear of an ancient reptile.

According to the study, the shape of the inner ear offers reliable signs as to whether an animal soared gracefully through the air, flew only fitfully, walked on the ground, or sometimes went swimming. In some cases, the inner ear even indicates whether a species did its parenting by listening to the high-pitched cries of its babies.

"Of all the structures that one can reconstruct from fossils, the inner ear is perhaps that which is most similar to a mechanical device," said Yale paleontologist Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, senior author of the new study, published in the journal Science.

"It's so entirely dedicated to a particular set of functions. If you are able to reconstruct its shape, you can reasonably draw conclusions about the actual behavior of extinct animals in a way that is almost unprecedented," said Bhullar, who is an assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences and an assistant curator at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Working with colleagues at the American Museum of Natural History, Bhullar and first author Michael Hanson of Yale compiled a matrix of inner ear data for 128 species, including modern-day animals such as birds and crocodiles, along with dinosaurs such as Hesperornis, Velociraptor, and the pterosaur Anhanguera.

Hesperornis, an 85-million-year-old bird-like species that had both teeth and a beak, was the inspiration for the research. The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History has the world's only three-dimensional fossil that preserves a Hesperornis inner ear.

"I was aware of literature associating cochlear dimensions with hearing capability, and semicircular canal structure with locomotion in reptiles and birds, so I became curious as to how Hesperornis would fit into the picture," said Hanson, a graduate student at Yale.

Hanson and Bhullar analyzed the Hesperornis inner ear with CT scanning technology to determine its three-dimensional shape.

Next, the researchers conducted the same analysis with a variety of other fossils -- and current species -- to determine whether the inner ear provided strong indications of behavior. In many cases, the researchers created 3D models from crushed or partially-crushed skull fossils.

After assembling the data, the researchers found clusters of species with similar inner ear traits. The clusters, they said, correspond with the species' similar ways of moving through and perceiving the world.

Several clusters were the result of the structure of the top portion of the inner ear, called the vestibular system. This, said Bhullar, is "the three-dimensional structure that tells you about the maneuverability of the animal. The form of the vestibular system is a window into understanding bodies in motion."

One vestibular cluster corresponded with "sophisticated" fliers, species with a high level of aerial maneuverability. This included birds of prey and many songbirds.

Another cluster centered around "simple" fliers like modern fowl, which fly in quick, straight bursts, and soaring seabirds and vultures. Most significantly, the inner ears of birdlike dinosaurs called troodontids, pterosaurs, Hesperornis, and the "dino-bird" Archaeopteryx fall within this cluster.

The researchers also identified a cluster of species which had a similar elongation of the lower portion of the inner ear -- the cochlear system -- that has to do with hearing range. This cluster featured a fairly large group of species, including all modern birds and crocodiles, which together form a group called archosaurs, the "ruling reptiles."

Bhullar said the data suggest that the cochlear shape's transformation in ancestral reptiles coincided with the development of high-pitched location, danger, and hatching calls in juveniles.

It implies that adults used their new inner ear feature to parent their young, the researchers said.

"All archosaurs sing to each other and have very complex vocal repertoires," Bhullar said. "We can reasonably infer that the common ancestors of crocodiles and birds also sang. But what we didn't know was when that occurred in the evolutionary line leading to them. We've discovered a transitional cochlea in the stem archosaur Euparkeria, suggesting that archosaur ancestors began to sing when they were swift little predators a bit like reptilian foxes."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the study are Mark Norell and Eva Hoffman of the American Museum of Natural History.

The Yale Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies, the American Museum of Natural History, and the National Science Foundation funded the research.

The findings, published in the journal Science today, demonstrate how integrating vertical descent and horizontal gene transfer can be used to infer the root of the bacterial tree and the nature of the last bacterial common ancestor.

Bacteria comprise a very diverse domain of single-celled organisms that can be found almost everywhere on Earth. All Bacteria are related and derive from a common ancestral Bacterial cell. Until now, the shape of the bacterial tree of life and the placement of its root has been contested, but is necessary to shed light on the early evolution of life on our ...

The uncertainty principle, first introduced by Werner Heisenberg in the late 1920's, is a fundamental concept of quantum mechanics. In the quantum world, particles like the electrons that power all electrical product can also behave like waves. As a result, particles cannot have a well-defined position and momentum simultaneously. For instance, measuring the momentum of a particle leads to a disturbance of position, and therefore the position cannot be precisely defined.

In recent research, published in Science, a team led by Prof. Mika Sillanpää at Aalto University in Finland has shown that there is a way to get around ...

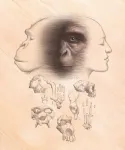

In the 150 years since Charles Darwin speculated that humans originated in Africa, the number of species in the human family tree has exploded, but so has the level of dispute concerning early human evolution. Fossil apes are often at the center of the debate, with some scientists dismissing their importance to the origins of the human lineage (the "hominins"), and others conferring them starring evolutionary roles. A new review out on May 7 in the journal Science looks at the major discoveries in hominin origins since Darwin's works and argues that fossil apes can inform us about essential aspects of ape and human evolution, including the nature ...

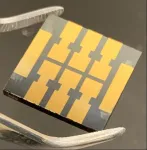

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A research team from Brown University has made a major step toward improving the long-term reliability of perovskite solar cells, an emerging clean energy technology. In a study to be published on Friday, May 7 in the journal Science, the team demonstrates a "molecular glue" that keeps a key interface inside cells from degrading. The treatment dramatically increases cells' stability and reliability over time, while also improving the efficiency with which they convert sunlight into electricity.

"There have been great strides ...

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center researchers added to the understanding of the protective immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus in a study published in April in iScience. The team found that approximately 3% of the population is asymptomatic, which means that their bodies can get rid of the virus without developing signs of illness.

The researchers screened more than 60,000 blood samples from symptomless individuals in the Southeastern U.S., including Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina, for the IgG antibody to the viral spike protein.

What began as a highly collaborative statewide effort to detect SARS-CoV-2 accurately, ...

Recently published research from the University of Arizona Health Sciences shows that advanced-stage kidney cancer is more common in Hispanic Americans and Native Americans than in non-Hispanic whites, and that both Hispanic Americans and Native Americans in Arizona have an increased risk of mortality from the disease.

"We knew from our past research that Hispanic Americans and Native Americans have a heavier burden of kidney cancer than non-Hispanic whites," said Ken Batai, PhD, a Cancer Prevention and Control Program research member at the UArizona Cancer Center and research assistant professor of urology in the College of Medicine - Tucson. "But we also know that around 90% of the Hispanic population in Arizona is Mexican American - either U.S.-born or Mexican-born ...

The air in the United States and Western Europe is much cleaner than even a decade ago. Low-sulfur gasoline standards and regulations on power plants have successfully cut sulfate concentrations in the air, reducing the fine particulate matter that harms human health and cleaning up the environmental hazard of acid rain.

Despite these successes, sulfate levels in the atmosphere have declined more slowly than sulfur dioxide emissions, especially in wintertime. This unexpected phenomenon suggests sulfur dioxide emission reductions are less efficient than expected for cutting sulfate aerosols. A new study led by Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech), Hokkaido University and the University ...

The ability of antibodies to recognize specific cancer cells is used in oncology to specifically target those cells with small active agents. Research published in the journal Angewandte Chemie shows that scientists have now built a transport system that delivers even large protein-based drugs into cancer cells. This study demonstrates how proteins can arrive at their target intact, protected from destructive proteases by polymer brushes.

Developing anticancer treatments involves two recurring problems for researchers. An active agent needs to be able to kill the body's cells at the root of the cancer, and it should be active in target cancer cells rather than in healthy cells. Many medical researchers ...

When you save an image to your smartphone, those data are written onto tiny transistors that are electrically switched on or off in a pattern of "bits" to represent and encode that image. Most transistors today are made from silicon, an element that scientists have managed to switch at ever-smaller scales, enabling billions of bits, and therefore large libraries of images and other files, to be packed onto a single memory chip.

But growing demand for data, and the means to store them, is driving scientists to search beyond silicon for materials that can push memory devices to higher densities, ...

For millennia, humans in the high latitudes have been enthralled by auroras--the northern and southern lights. Yet even after all that time, it appears the ethereal, dancing ribbons of light above Earth still hold some secrets.

In a new study, physicists led by the University of Iowa report a new feature to Earth's atmospheric light show. Examining video taken nearly two decades ago, the researchers describe multiple instances where a section of the diffuse aurora--the faint, background-like glow accompanying the more vivid light commonly associated with auroras--goes dark, as if scrubbed by a giant blotter. Then, after a short period of time, the blacked-out section suddenly reappears.

The researchers say the behavior, which they call "diffuse ...