(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - An 18.5 million-year-old fossil found in Panama provides evidence of a new species and is the oldest reliable example of a climbing woody vine known as a liana from the soapberry family. The discovery sheds light on the evolution of climbing plants.

The new species, named Ampelorhiza heteroxylon, belongs to a diverse group of tropical lianas called Paullinieae, within the soapberry family (Sapindaceae). More than 475 species of Paullinieae live in the tropics today.

Researchers identified the species from fossilized roots that revealed features known to be unique to the wood of modern climbing vines, adaptations that allow them to twist, grow and climb.

The study, "Climbing Since the Early Miocene: The Fossil Record of Paullinieae (Sapindaceae)," was published April 7 in the journal PLOS ONE.

"This is evidence that lianas have been creating unusual wood, even in their roots, as far back as 18 million years ago," said wood anatomist Joyce Chery '13, assistant research professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant Biology Section, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and a corresponding author of the paper.

"Before this discovery, we knew almost nothing about when or where these lianas evolved or how rapidly they diversified," said first author Nathan Jud, assistant professor of plant biology at William Jewell College and a former Cornell postdoctoral researcher.

Panama was a peninsula 18.5 to 19 million years ago, a volcanic landscape covered with tropical forest in North America and separated from South America by a Central American seaway. While these forests contained North American animals, the plants mostly descended from South American tropical plants that had dispersed across the seaway, Jud said.

"The fossil we described is the oldest macrofossil of these vines," he said, "and they were among the plants that made it to North America long before the Great American Biotic Interchange when large animals moved between the continents some 3 million years ago."

In the study, the researchers made thin slices of the fossil, examined the arrangements and dimensions of tissues and water conducting vessels under a microscope and created a database of all the features. They then studied the literature to see how these features matched up with the living and fossil records of plants.

"We were able to say, it really does look like it's a fossil from the Paullinieae group, given the anatomical characteristics that are similar to species that live today," Chery said.

During their analyses, the researchers identified features that are characteristic of lianas. Most trees and shrubs have water-conducting tissues (which transport water and minerals from roots to leaves) that are all roughly the same size when viewed in a cross-section; in vines, these conduits come in two sizes, big and small, which is exactly what the researchers discovered in the fossil.

"This is a feature that is pretty specific to vines across all sorts of families," Chery said.

The two vessel sizes provide insurance for a twisting and curving plant, as large vessels provide ample water flow, but are also vulnerable to collapse and develop cavities that disrupt flow. The series of smaller vessels offers a less vulnerable backup water transport system, Chery said.

Also, cross-sections of the wood in trees and shrubs are circular, but in the fossil, and in many living vines, such cross-sections are instead irregular and lobed.

Thirdly, on the walls of those vascular vessels, they found long horizontal perforations that allow for water to flow in lateral directions. That is a distinguishing feature of lianas in the soapberry family, Chery said.

In future work, now that they can place the lianas of Sapindaceae to 18.5 million years ago, the researchers intend to continue their investigation of the evolutionary history and diversification of this family. Chery also plans to investigate how wood has evolved in this group of vines, including identifying the genes that contribute to lobe-shaped stems.

INFORMATION:

The study was partly funded by the National Science Foundation.

The functions of water-dominated ecosystems can be considerably influenced and changed by hydrological fluctuation. The varying states of redox-active substances are of crucial importance here. Researchers at the University of Bayreuth have discovered this, in cooperation with partners from the Universities of Tübingen and Bristol and the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Halle-Leipzig. They present their discovery in the journal Nature Geoscience. The new study enables a more precise understanding of the biogeochemical processes that contribute to the degradation of pollutants and the reduction of greenhouse gas ...

More than ever, patients are using telehealth to ask doctors and nurses about worrying blood-pressure readings, nauseating migraines and stubborn foot ulcers. But for patients with chronic conditions, how frequent should telehealth appointments be? Can that frequency change? Under what conditions?

West Virginia University researcher Jennifer Mallow is trying to answer these questions. In a new project, she and her colleagues completed a systematic review of studies that dealt with telehealth and chronic conditions. They found that--in general--telehealth services benefitted patients more if they ...

A comprehensive review into what we know about COVID-19 and the way it functions suggests the virus has a unique infectious profile, which explains why it can be so hard to treat and why some people experience so-called "long-COVID", struggling with significant health issues months after infection.

There is growing evidence that the virus infects both the upper and lower respiratory tracts - unlike "low pathogenic" human coronavirus sub-species, which typically settle in the upper respiratory tract and cause cold-like symptoms, or "high pathogenic" viruses such as those that cause SARS and ARDS, which typically settle in the lower respiratory tract.

Additionally, more frequent multi-organ impacts, and blood clots, and ...

Which wound cuts deeper: the loss of an only child or loss of a spouse? A new study led by researchers at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing and Fudan University suggests that Chinese parents find the loss of an only child to be approximately 1.3 times as psychologically distressing than the loss of a spouse. The findings are published in the journal Aging & Mental Health.

Older adults in China rely heavily on family support, particularly from their adult children. Filial piety--the Confucian idea describing a respect for one's parents and responsibility for adult children to care for ...

Observing how cells stick to surfaces and their motility is vitally important in the study of tissue maintenance, wound healing and even understanding how cancers progress. A new paper published in EPJ Plus, by Raj Kumar Sadhu, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel, takes a step towards a deeper understanding of these processes.

"Cell adhesion is the ability of a cell to stick to another cell or an extracellular matrix. This process is important in order to understand how cells interact and coordinate their behaviour in multicellular organisms," says sadhu. "We theoretically model the adhesion of a cell-like vesicle by describing the cell as a three-dimensional vesicle adhering on a flat substrate with a constant adhesion interaction."

Alongside ...

Neuroblastoma is a childhood cancer, most commonly affecting children aged between 2 -3 and can be fatal. Since the tumour cells resemble certain cells in the adrenal glands, a joint research group from MedUni Vienna's Center for Brain Research and the Swedish Karolinska Institute investigated the cellular origin of these cells and sympathetic neurons during the embryonic development of human adrenal glands. During the course of their investigations, they discovered a previously unknown cell type that might potentially be the origin of the tumour cells.

Treatments for this disease are extremely aggressive and challenging ...

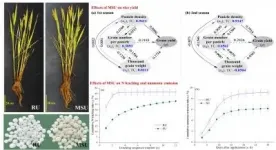

The applied nitrogen in crop production is easily lost through ammonia emission and nitrogen leaching. Therefore, many attempts have been made on the development of novel slow-release fertilizers to reduce nitrogen loss and improve crop production.

A research team led by Prof. WU Yuejin from the Institute of Intelligent Machines of the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science developed a novel matrix-based slow-release urea (MSU) recently to improve nitrogen use efficiency in rice production, and they assessed the performances of it.

"MSU is a promising fertilizer for rice production," said WU, "as less nitrogen loss and greater soil nitrogen ...

Physicists at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) have for the first time been able to prove a long-predicted but as yet unconfirmed fundamental effect. In Faraday chiral anisotropy, the propagation characteristics of light waves are changed simultaneously by the natural and magnetic-field induced material properties of the medium through which the light travels. The researchers obtained proof that this is the case by conducting experiments using nickel helices at the nanometre scale. Their findings have now been published in the academic journal 'Physical Review Letters'.

Light is transmitted as sine waves consisting of crossed electric and magnetic fields and interacts with matter. This ...

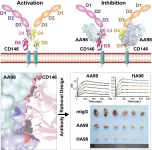

Recently, Prof. XIE Can from the High Magnetic Field Laboratory of the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), in a collaboration with Prof. YAN Xiyun's lab from the Institute of Biophysics, reported the structural basis of mAb AA98's inhibition on CD146-mediated endothelial cells (EC) activation and designed higher affinity monoclonal antibody HA98 for cancer treatment.

CD146 is an adhesion molecule that plays important roles in angiogenesis, cancer metastasis, and immune response. Prof. YAN Xiyun's lab has been focused on the function of CD146 and the mechanism ...

Australia, the driest inhabited continent, is prone to natural disasters and wild swings in weather conditions - from floods to droughts, heatwaves and bushfires.

Now two new Flinders University studies of long-term hydro-climatic patterns provide fresh insights into the causes of the island continent's strong climate variability which affect extreme wet or dry weather and other conditions vital to water supply, agriculture, the environment and the nation's future.

For the first time, researchers from the National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training (NCGRT) at Flinders have revealed a vegetation-mediated seesaw wetting-drying phenomenon between eastern and western Australia. ...