Planets like Earth that orbit within a solar system's Goldilocks zone, with conditions supporting liquid water and a rich atmosphere, are more likely to harbor life. As it turns out, how that planet came together also determines whether it captured and retained certain volatile elements and compounds, including nitrogen, carbon and water, that give rise to life.

In a study published in Nature Geoscience, Rice graduate student and lead author Damanveer Grewal and Professor Rajdeep Dasgupta show the competition between the time it takes for material to accrete into a protoplanet and the time the protoplanet takes to separate into its distinct layers -- a metallic core, a shell of silicate mantle and an atmospheric envelope in a process called planetary differentiation -- is critical in determining what volatile elements the rocky planet retains.

Using nitrogen as proxy for volatiles, the researchers showed most of the nitrogen escapes into the atmosphere of protoplanets during differentiation. This nitrogen is subsequently lost to space as the protoplanet either cools down or collides with other protoplanets or cosmic bodies during the next stage of its growth.

This process depletes nitrogen in the atmosphere and mantle of rocky planets, but if the metallic core retains enough, it could still be a significant source of nitrogen during the formation of Earth-like planets.

Dasgupta's high-pressure lab at Rice captured protoplanetary differentiation in action to show the affinity of nitrogen toward metallic cores.

"We simulated high pressure-temperature conditions by subjecting a mixture of nitrogen-bearing metal and silicate powders to nearly 30,000 times the atmospheric pressure and heating them beyond their melting points," Grewal said. "Small metallic blobs embedded in the silicate glasses of the recovered samples were the respective analogs of protoplanetary cores and mantles."

Using this experimental data, the researchers modeled the thermodynamic relationships to show how nitrogen distributes between the atmosphere, molten silicate and core.

"We realized that fractionation of nitrogen between all these reservoirs is very sensitive to the size of the body," Grewal said. "Using this idea, we could calculate how nitrogen would have separated between different reservoirs of protoplanetary bodies through time to finally build a habitable planet like Earth."

Their theory suggests that feedstock materials for Earth grew quickly to around moon- and Mars-sized planetary embryos before they completed the process of differentiating into the familiar metal-silicate-gas vapor arrangement.

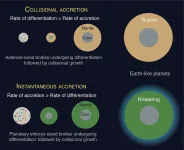

In general, they estimate the embryos formed within 1-2 million years of the beginning of the solar system, far sooner than the time it took for them to completely differentiate. If the rate of differentiation was faster than the rate of accretion for these embryos, the rocky planets forming from them could not have accreted enough nitrogen, and likely other volatiles, critical to developing conditions that support life.

"Our calculations show that forming an Earth-size planet via planetary embryos that grew extremely quickly before undergoing metal-silicate differentiation sets a unique pathway to satisfy Earth's nitrogen budget," said Dasgupta, the principal investigator of CLEVER Planets, a NASA-funded collaborative project exploring how life-essential elements might have come together on rocky planets in our solar system or on distant, rocky exoplanets.

"This work shows there's much greater affinity of nitrogen toward core-forming metallic liquid than previously thought," he said.

The study follows earlier works, one showing how the impact by a moon-forming body could have given Earth much of its volatile content, and another suggesting that the planet gained more of its nitrogen from local sources in the solar system than once believed.

In the latter study, Grewal said, "We showed that protoplanets growing in both inner and outer regions of the solar system accreted nitrogen, and Earth sourced its nitrogen by accreting protoplanets from both of these regions. However, it was unknown as to how the nitrogen budget of Earth was established."

"We are making a big claim that will go beyond just the topic of the origin of volatile elements and nitrogen, and will impact a cross-section of the scientific community interested in planet formation and growth," Dasgupta said.

INFORMATION:

Rice undergraduate intern Taylor Hough and research intern Alexandra Farnell, then a student at St. John's School in Houston and now an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, are co-authors of the study.

NASA grants, including one via the FINESST program, and a Lodieska Stockbridge Vaughn Fellowship at Rice supported the research.

Read the paper at https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00733-0.

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Much of Earth's nitrogen was locally sourced: http://news.rice.edu/2021/01/21/much-of-earths-nitrogen-was-locally-sourced/

Planetary collision that formed the moon made life possible on Earth: https://news.rice.edu/2019/01/23/planetary-collision-that-formed-the-moon-made-life-possible-on-earth-2/

What recipes produce a habitable planet? http://news.rice.edu/2018/09/17/what-recipes-produce-a-habitable-planet-2/

Breathing? Thank volcanoes, tectonics and bacteria: http://news.rice.edu/2019/12/02/breathing-thank-volcanoes-tectonics-and-bacteria/

ExPeRT: Experimental Petrology Rice Team (Dasgupta group): https://www.dasgupta.rice.edu/expert/people/

CLEVER Planets: http://cleverplanets.org

Rice Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences: https://earthscience.rice.edu

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: https://www.rice.edu

Images for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/04/0405_NITRO-5-WEB.jpg

Nitrogen-bearing, Earth-like planets can be formed if their feedstock material grows quickly to around moon- and Mars-sized planetary embryos before separating into core-mantle-crust-atmosphere, according to Rice University scientists. If metal-silicate differentiation is faster than the growth of planetary embryo-sized bodies, then solid reservoirs fail to retain much nitrogen and planets growing from such feedstock become extremely nitrogen-poor. (Credit: Illustration by Amrita P. Vyas/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/03/0329_NITROGEN-1-WEB.jpg

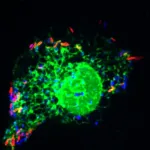

Rice University geochemists analyzed experimental samples of coexisting metals and silicates to learn how they would chemically interact when placed under pressures and temperatures similar to those experienced by differentiating protoplanets. Using nitrogen as a proxy, they theorize that how a planet comes together has implications for whether it captures and retains volatile elements essential to life. (Credit: Tommy LaVergne/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/04/0405_NITRO-4-WEB.jpg

Rice University graduate student Damanveer Grewal, left, and geochemist Rajdeep Dasgupta discuss their experiments in the lab, where they compress complex mixtures of elements to simulate conditions deep in protoplanets and planets. In a new study, they determined that how a planet comes together has implications for whether it captures and retains the volatile elements, including nitrogen, carbon and water, essential to life. (Credit: Tommy LaVergne/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Jeff Falk

713-348-6775

jfalk@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu