(Press-News.org) Pregnant women who are hospitalized with COVID-19 and viral pneumonia are less likely than non-pregnant women to die from these infections, according to a new study by researchers with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) and the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM).

The study was published today in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study examined medical records from nearly 1,100 pregnant patients and more than 9,800 non-pregnant women ages 15 to 45 who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and pneumonia. Less than 1% of the pregnant patients died from COVID-19 compared to 3.5% of non-pregnant patients, according to the study findings.

Currently, the Centers for Diseases and Control and Prevention (CDC) say pregnant women are at a high risk of developing severe complications from COVID-19.

"We were surprised when we first analyzed the data," said Beth Pineles, MD, PhD, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth and first author of the study. "We had expected to confirm the results of the CDC and other U.S. researchers showing that pregnancy increases the risk for dying from COVID-19. However, once we compared our results to data from the UK and reviewed the CDC reports more carefully, we found confirmation that our results were likely to represent the true risks of COVID-19 in these populations, despite the limitation of pregnant women being younger and healthier than non-pregnant women."

Researchers found that pregnant patients were more likely to be younger and have fewer health conditions, including diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and chronic lung disease, compared to the non-pregnant patients. Given the small number of deaths seen in the study, researchers were unable to determine whether these conditions significantly affected the difference in mortality risk between pregnant and non-pregnant patients.

"At the start of the pandemic, the existing data showed that pregnant women would face severe complications if they contracted the virus," said Jacqueline Parchem, MD, assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth and co-author on the study. "While pregnant women are certainly susceptible to severe complications of COVID-19 including death, we view these data has reassuring that the absolute risk of death is low."

Pineles and Parchem still want to encourage pregnant women to wear their mask and get their COVID-19 shot. The risk of getting severely ill or dying is low, but it is still much higher than for healthy pregnant women without COVID-19.

"I think this is reassuring news for women who are pregnant and worried about getting infected with COVID-19 as new variants emerge," said Anthony Harris, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology & public health at UMSOM and senior and corresponding author of the study.

INFORMATION:

Additional UMSOM authors include Katherine Goodman, JD, PhD; Lisa Pineles, MA; Lyndsay O'Hara, PhD; Gita Nadimpalli, MD, MPH; Laurence Magder, PhD; and Jonathan Baghdadi, MD, PhD.

Release adapted from UMSOM.

For media inquiries, call 713-500-3030.

Lichen communities may take decades -- and in some cases up to a century -- to fully return to chaparral ecosystems after wildfire, finds a study from the University of California, Davis, and Stanford University.

The study, published today in the journal Diversity and Distributions, is the most comprehensive to date of long-term lichen recolonization after fire.

Unlike conifer forests, chaparral systems in California are historically adapted to high-intensity fires -- they burn hot, fast and tend to regenerate quickly. However, with more frequent fires predicted under a drier, warming climate ...

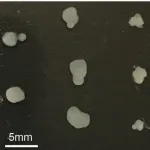

In order for metal nanomaterials to deliver on their promise to energy and electronics, they need to shape up -- literally.

To deliver reliable mechanical and electric properties, nanomaterials must have consistent, predictable shapes and surfaces, as well as scalable production techniques. UC Riverside engineers are solving this problem by vaporizing metals within a magnetic field to direct the reassembly of metal atoms into predictable shapes. The research is published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

Nanomaterials, which are made of particles measuring 1-100 nanometers, are typically ...

Almost half (47.5%) of women with babies aged six months or younger met the threshold for postnatal depression during the first COVID-19 lockdown, more than double average rates for Europe before the pandemic (23%), finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

Women described feelings of isolation, exhaustion, worry, inadequacy, guilt, and increased stress. Many grieved for what they felt were lost opportunities for them and their baby, and worried about the developmental impact of social isolation on their new little one.

Those whose partners were unable or unavailable to help with parenting and domestic ...

Air quality in Spain temporarily improved during the first wave of COVID-19, largely as a result of mobility restrictions. Until recently, however, the effect of this improvement on the health of the population was poorly understood. A new study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation, together with the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC-CNS), has estimated that this improvement in air quality prevented around 150 premature deaths in Spain's provincial capital cities.

Several analyses have estimated the mortality reduction from improved ...

The tightly defined ratios of metals in MOFs makes them ideal starting materials for novel catalyst creation.

Heating bimetallic metal organic frameworks (MOFs) until their porous structure collapses into nanoparticles can be a highly effective way to make catalysts. This novel approach to catalyst design has now been used by KAUST and Spanish researchers to make a robust catalyst that converts carbon dioxide (CO2) into carbon monoxide (CO) gas with unprecedented selectivity.

The benefit of this method pioneered at KAUST is that it can generate mixed metal catalytic nanoparticles that have proven challenging or impossible to make by conventional means.

Capturing ...

Published today in Nature Communications, the team from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute), Alfred Health and Monash University sought to understand which patients would recover quickly from influenza and which would become severely ill.

The four-year project took samples from patients hospitalised with influenza at up to five time points during their hospital stay, and 30 days after discharge. They analysed the breadth of the immune response, enabling them to describe the specific roles of several different types of immune cells, including killer and helper T cells, B cells and innate cells.

University of Melbourne Dr Oanh Nguyen, Research Fellow at the Doherty Institute, said two significant findings of the research include understanding ...

A group of researchers from Osaka University developed a quadruped robot platform that can reproduce the neuromuscular dynamics of animals (Figure 1), discovering that a steady gait and experimental behaviors of walking cats emerged from the reflex circuit in walking experiments on this robot. Their research results were published in Frontiers in Neurorobotics.

It was thought that a steady gait in animals is generated by complex nerve systems in the brain and spinal marrow; however, recent research shows that a steady gait is produced by the reflex circuit alone. Scientists discovered a candidate of reflex circuit to generate the steady walking motion ...

Dr. HAN Fangpu's group from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences reports the identification and functional study of the maize Knl1 gene in an article published online in PNAS. The gene is a major component of the KMN network that links centromeric DNA and the plus-ends of spindle microtubules. It also plays an important role in kinetochore protein recruitment.

The kinetochore complex that assembles on the centromeres mediates the proper partitioning of chromosomes to daughter cells during the cell cycle. However, kinetochore proteins undergo frequent mutations and coevolve with their interaction partners, leading to great diversity in kinetochore composition in eukaryotes.

Functional ...

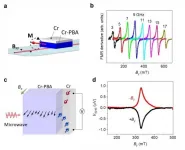

A team of researchers, affiliated with UNIST has recently introduced a new class of magnetic materials for spin caloritronics. Published in the February 2021 issue of Nature Communications, the demonstrated STE applications of a new class of magnets will pave the way for versatile recycling of ubiquitous waste heat. This breakthrough has been led by Professor Jung-Woo Yoo and his research team in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at UNIST.

Spin thermoelectrics is an emerging thermoelectric technology that offers energy harvesting from waste heat. ...

Like many around the world, the lab of Professor Mriganka Sur in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT has embraced the young technology of cerebral organoids, or "minibrains," for studying human brain development in health and disease. By making a surprising finding about a common practice in the process of growing the complex tissue cultures, the lab has produced both new guidance that can make the technology better, and also new insight into the important roles a prevalent enzyme takes in natural brain development.

To make organoids, scientists take skin cells from a donor, induce them to become stem cells and then culture those in a bioreactor, guiding their development with the addition of growth ...