(Press-News.org) Roads can be barriers to wildlife of all sorts, and scientists have studied road impacts on animals ranging from Florida panthers and grizzly bears to box turtles, mice, rattlesnakes and salamanders.

But much less is known about the impact of roads on pollinating insects such as bees and to what extent these structures disrupt insect pollination, which is essential to reproduction in many plant species.

In a paper published online May 10 in the Journal of Applied Ecology, University of Michigan researchers describe how they used fluorescent pigment as an analog for pollen. They applied the luminous pigment to the flowers of roadside plants to study how roads affected the movement of pollen between plants at 47 sites in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The researchers found that plants across a road from pigment-added plants received significantly less pigment than plants on the same side of the road. The study also suggests relatively simple ways to reduce this road-barrier effect.

"Our study shows that roads and paths pose a significant barrier to bee movement and therefore substantially reduce pollen transfer," said study author Gordon Fitch, a doctoral candidate in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. His co-lead author is Chatura Vaidya, also an EEB doctoral candidate.

The study focused on two species of insect-pollinated flowering plants native to the region, wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) and threadleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata).

At each site, three potted plants were placed along the roadside on a warm, sunny morning. Luminous pigment was applied to the reproductive structures in the flowers of one plant (the "pigment-added" plant).

Then a second plant (the "across" plant) was placed across the road from the pigment-added plant, and the distance between the two plants was measured. Finally, a third plant (the "along" plant) was placed on the same side of the road as the pigment-added plant, at the same distance from the pigment-added plant as the "across" plants.

At most sites, both species of flowering plants were deployed in this fashion.

The researchers left the plants outside for the day, collected them in the evening, and brought them to a dark location. An ultraviolet flashlight was used to determine how patterns of pigment transfer varied, depending on whether the plants were located on the same side of the road or on opposite sides of the road.

To do this, the researchers counted the number of flowers on each plant that held pigment. Because wind and nonpollinating insects can sometimes transfer pigment, only flowers with pigment on their reproductive parts, not the petals, were counted.

Fitch and Vaidya found that being across the road reduced pigment transfer by 50% for the threadleaf coreopsis plants and by 34% for wild bergamot plants, compared to plants on the same side of the road.

"Ours is the first well-replicated study to examine how roads impact bee movement," Fitch said. "Moreover, we used an innovative technique relying on pigment as a pollen analog--rather than direct observation of insect behavior--which allowed us to collect data efficiently. As such, we are also the first to show that roads disrupt the movement of pollen between plants."

During the study, Fitch and Vaidya observed 65 insect visits to threadleaf coreopsis plants and 356 to wild bergamot plants. Ninety-seven percent of the visits were from bees.

Bees are indispensable pollinators, supporting both agricultural productivity and the diversity of flowering plants worldwide. In recent decades, both native bees and managed honeybee colonies have seen population declines blamed on multiple interacting factors including habitat loss, parasites and disease, and pesticide use.

Fitch and Vaidya found that reduced pigment transfer was driven by the size of the road, as well as the size of the bees: As the number of road lanes increased, or as the size of the bee decreased, the effect was greater.

Pigment transfer across roads with three or more lanes of traffic was rare for either plant species, they found, suggesting that medium-sized and large roads may impede the movement of bees sufficiently to impact foraging and pollination.

The researchers recommend the evaluation and implementation of strategies to make roads less of a barrier to pollinators--without spending huge sums of money to do so.

Wildlife crossing structures that have been used in North America and Europe to facilitate movement of animals through landscapes fragmented by roads include wildlife overpasses, bridges, culverts and pipes.

In a similar fashion, existing pedestrian overpasses could potentially be modified to help bees and other flying pollinators, simply by adding flower-containing planter boxes to the landscaping, Fitch said. He cautioned that such an approach is largely hypothetical and is untested.

Such measures could potentially dovetail with efforts in some cities to promote alternative modes of transportation and to reduce traffic accidents by using so-called road diets. This increasingly popular design strategy reduces the amount of a roadway dedicated to vehicular traffic through, for example, the addition of bicycle lanes or wider sidewalks.

In downtown Ann Arbor, recently installed examples of road diets include the protected, two-way bike lanes on William and Ashley streets.

"Since road width and traffic volume were major predictors of pigment transfer in our study, this suggests that road diets could also help reduce the effects of roads on flying insects, particularly if they included pollinator-friendly plantings," Fitch said.

INFORMATION:

Study: "Roads pose a significant barrier to bee movement, mediated by road size, traffic, and bee identity"

number is projected to increase by an additional 15 million miles or so by 2050.

Photos

(Boston)--Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a disease caused by cigarette smoking that reduces lung function and causes difficulty breathing. It is the third leading cause of death worldwide. Current treatments for COPD only affect symptoms, not progression. Identifying who is going to get COPD before they get it is key to figuring out how to intercept the disease at an early stage.

Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified a panel of genes that are active in smokers and ex-smokers who experience faster loss of lung function over time. They believe these genes could be useful to predict which people are most at risk for smoking-related ...

(Boston)--Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a global health problem. Almost half the adults over the age of 75 have some form of knee OA--one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Because there is no cure for knee OA, current treatment relies on accurately identifying and staging the disease.

Using an Artificial Intelligence-based approach known as deep learning, researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have now identified a new measure to determine the severity of knee osteoarthritis--named "subchondral bone length" (SBL).

There are only a handful of proven imaging markers of knee OA. Currently, medical imaging tools such as Magnetic ...

DALLAS - April 30, 2021 - UT Southwestern scientists successfully employed a new type of gene therapy to treat mice with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), uniquely utilizing CRISPR-Cas9-based tools to restore a large section of the dystrophin protein that is missing in many DMD patients. The approach, described online today in the journal Science Advances, could lead to a treatment for DMD and inform the treatment of other inherited diseases.

"Thousands of different mutations causing Duchenne have been identified, but they tend to cluster into certain parts of the dystrophin gene," says study leader END ...

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine researchers are the first to demonstrate that COVID-19 can be present in the penis tissue long after men recover from the virus.

The widespread blood vessel dysfunction, or endothelial dysfunction, that results from the COVID-19 infection could then contribute to erectile dysfunction, or ED, according to the study recently published in the World Journal of Men's Health. Endothelial dysfunction is a condition in which the lining of the small blood vessels fails to perform all of its functions normally. As a result, the tissues ...

Researchers have mapped out the changes in metabolism that occur after a heart attack, publishing their findings today in the open-access eLife journal.

Their study in mice reveals certain genes and metabolic processes that could aid or hinder recovery, and might be good targets for treatments to prevent damage after a heart attack.

"Although some studies have looked at how changes in individual body tissues underlie mechanisms of disease, the crosstalk between different tissues and their dysregulation has not been examined in heart attacks or other cardiovascular-related complications," explains first author Muhammad Arif, a PhD student at KTH Royal ...

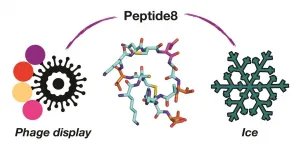

Controlling, and mitigating the effects of ice growth is crucial to protect infrastructure, help preserve frozen cells and to enhance texture of frozen foods. An international collaboration of Warwick Scientists working with researchers from Switzerland have used a phage display platform to discover new, small, peptides which function like larger antifreeze proteins. This presents a route to new, easier to synthesise, cryoprotectants.Caption: Using viruses (phage display) to identify the one molecule in a billion (peptide8) that controls the formation of ice. Credit: University of Warwick

Ice binding proteins, which includes antifreeze proteins, are produced by a large range of species from fish, ...

An investigational gene therapy can safely restore the immune systems of infants and children who have a rare, life-threatening inherited immunodeficiency disorder, according to research supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers found that 48 of 50 children who received the gene therapy retained their replenished immune system function two to three years later and did not require additional treatments for their condition, known as severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency, or ADA-SCID. The findings were published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

ADA-SCID, ...

Low doses of a four-drug combination helps prevent the spread of cancer in mice without triggering drug resistance or recurrence, shows a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest a new approach to preventing cancer metastasis in patients by simultaneously targeting multiple pathways within a metastasis-promoting network. They may also help identify people who would most likely benefit from such treatment.

Metastasis, the spread of cancerous cells through the body, is a common cause of cancer-related deaths. Current approaches to treating metastatic cancer have focused on high doses of individual drugs or drug combinations to hinder pathways that promote the spread of cancer cells. But these approaches can be toxic to the patient, and may inadvertently activate other pathways ...

A new study from the University of Chicago has found that the photosynthetic bacterium Synechococcus elongatus uses a circadian clock to precisely time DNA replication, and that interrupting this circadian rhythm prevents replication from completing and leaves chromosomes unfinished overnight. The results, published online on May 10 in Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences, have implications for understanding how interrupted circadian rhythms can impact human health.

Circadian rhythms are the internal 24-hour clock possessed by most organisms on earth, regulating ...

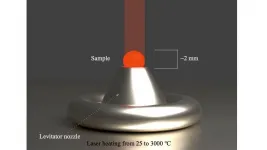

Argonne scientists across several disciplines have combined forces to create a new process for testing and predicting the effects of high temperatures on refractory oxides.

Cast iron melts at around 1,200 degrees Celsius. Stainless steel melts at around 1,520 degrees Celsius. If you want to shape these materials into everyday objects, like the skillet in your kitchen or the surgical tools used by doctors, it stands to reason that you would need to create furnaces and molds out of something that can withstand even these extreme temperatures.

That's where refractory oxides come in. These ceramic materials can stand up to blistering heat and retain their shape, which makes them useful for all kinds of things, from kilns ...