(Press-News.org) A 'slow-motion' earthquake lasting 32 years - the slowest ever recorded - eventually led to the catastrophic 1861 Sumatra earthquake, researchers at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have found.

The NTU research team says their study highlights potential missing factors or mismodelling in global earthquake risk assessments today.

'Slow motion' earthquakes or 'slow slip events' refer to a type of long, drawn-out stress release phenomenon in which the Earth's tectonic plates slide against one another without causing major ground shaking or destruction. They typically involve movements of between a few cm/year to cm/day.

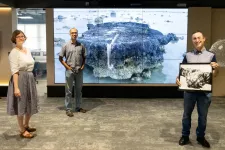

The NTU team made the surprise discovery while studying historic sea-levels using ancient corals called 'microatolls' at Simeulue Island, located off the coast of Sumatra. Growing both sideways and upwards, the disc-shaped coral microatolls are natural recorders of changes in sea level and land elevation, through their visible growth patterns.

Using data from the microatolls and combining them with simulations of the motion of the Earth's tectonic plates, the NTU team found that from 1829 until the Sumatra earthquake in 1861, south-eastern Simeulue Island was sinking faster than expected into the sea.

This slow slip event was a gradual process that relieved stress on the shallow part of where two tectonic plates met, said the NTU team. However, this stress was transferred to a neighbouring deeper segment, culminating in the massive 8.5 magnitude earthquake and tsunami in 1861 which led to enormous damage and loss of life.

The discovery marks the longest slow slip event ever recorded and will change global perspectives on the timespan and mechanisms of the phenomenon, says the NTU team. Scientists previously believed that slow slip events take place only over hours or months, but the NTU research shows that they could, in fact, go on for decades without triggering the disastrous shaking and tsunamis seen in historical records.

Lead author of the study, Rishav Mallick, a PhD student at the NTU Asian School of Environment, said, "It is interesting just how much we were able to discover from just a handful of ideally located coral sites. Thanks to the long timespans of the ancient corals, we were able to probe and find answers to secrets of the past. The method that we adopted in this paper will also be useful for future studies of other subduction zones - places that are prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. Our study can therefore contribute to better risk assessments in future."

Co-author Assistant Professor Aron Meltzner from the Earth Observatory of Singapore at NTU said, "When we first found these corals more than a decade ago, we knew from their growth patterns that something strange must have been going on while they grew. Now we finally have a viable explanation."

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature Geoscience in May, led the authors to suggest that current earthquake risk assessments may be overlooking ongoing slow slip events in the observations, and hence not properly considering the potential for slow slip events to trigger future earthquakes and tsunamis.

Possible 'slow motion' earthquake ongoing at Enggano Island

Located far from land below kilometres of water, the shallower part of the subduction zone is typically 'quieter' and does not produce as many earthquakes. Its distant location also makes it difficult for land-based scientific instruments to detect activities and for scientists to understand what is going on.

Many scientists have therefore tended to interpret the 'quietness' of the shallow part of the subduction zone to mean that the tectonic plates lying underneath to be sliding along steadily and harmlessly.

Though this might be correct in some cases, the NTU study found that this sliding is not as steady as assumed and can occur in slow slip events.

Elaborating on their findings, Rishav said, "Because such slow slip events are so slow, we might have been missing them as current instrumental records are generally only up to ten years long."

He added, "If similar behaviour is observed leading up to earthquakes elsewhere, this process might eventually be recognised as an earthquake precursor."

Tapping on their methodology in the research, the NTU team also highlighted a potential ongoing drawn-out slow slip event at Enggano Island, Indonesia, located at about 100 km (60 miles) southwest of Sumatra.

Asst Prof Meltzner said, "If our findings are correct, this would mean that the communities living nearby this Indonesian island are potentially facing higher risk of tsunami and earthquake than what was previously thought. This suggests that models of risk and mitigation strategies need updating."

INFORMATION:

New research at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden suggests a link between psychosis and a genetic change that affects the brain's immune system. The study published in Molecular Psychiatry may impact the development of modern medicines for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Psychosis affects approximately 2-3 per cent of the population and is characterized by a change in the perception of reality, often with elements of hallucinations and paranoid reactions.

Most of the people affected are patients with schizophrenia, but people with bipolar disorder may also experience psychotic symptoms.

The antipsychotics available today often have insufficient efficacy, and for patients, ...

Anyone who's raised a child or a pet will know just how fast and how steady their growth seems to be. You leave for a few days on a work trip and when you come home the child seems to have grown 10cm! That's all well and good for the modern household, but how did dinosaurs grow up? Did they, too, surprise their parents with their non-stop growth?

A new study lead by Dr Kimberley Chapelle of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand suggests NOT. At least for one iconic southern African dinosaur species. By looking at the fossil ...

Can you feel the heat? To a thermal camera, which measures infrared radiation, the heat that we can feel is visible, like the heat of a traveler in an airport with a fever or the cold of a leaky window or door in the winter.

In a paper published in Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, an international group of applied mathematicians and physicists, including Fernando Guevara Vasquez and Trent DeGiovanni from the University of Utah, report a theoretical way of mimicking thermal objects or making objects invisible to thermal measurements. And it doesn't ...

A study across 55 hospitals in Queensland, Australia suggests that a recent state policy to introduce a minimum ratio of one nurse to four patients for day shifts has successfully improved patient care, with a 7% drop in the chance of death and readmission, and 3% reduction in length of stay for every one less patient a nurse has on their workload.

The study of more than 400,000 patients and 17,000 nurses in 27 hospitals that implemented the policy and 28 comparison hospitals is published in The Lancet. It is the first prospective evaluation of the ...

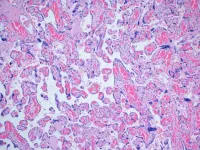

CHICAGO --- A new Northwestern Medicine study of placentas from patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy found no evidence of injury, adding to the growing literature that COVID-19 vaccines are safe in pregnancy.

"The placenta is like the black box in an airplane. If something goes wrong with a pregnancy, we usually see changes in the placenta that can help us figure out what happened," said corresponding author Dr. Jeffery Goldstein, assistant professor of pathology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine pathologist. "From what we can tell, the COVID vaccine does not damage the placenta."

The study will be published May 11 in the journal Obstetrics ...

TORONTO, ON - Geoscientists at the University of Toronto (U of T) and Istanbul Technical University have discovered a new process in plate tectonics which shows that tremendous damage occurs to areas of Earth's crust long before it should be geologically altered by known plate-boundary processes, highlighting the need to amend current understandings of the planet's tectonic cycle.

Plate tectonics, an accepted theory for over 60 years that explains the geologic processes occurring below the surface of Earth, holds that its outer shell is fragmented into continent-sized blocks of solid rock, called "plates," that slide over Earth's mantle, the rocky inner layer above ...

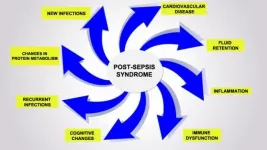

An article published in Frontiers in Immunology suggests that sepsis can cause alterations in the functioning of defense cells that persist even after the patient is discharged from hospital. This cellular reprogramming creates a disorder the authors call post-sepsis syndrome, whose symptoms include frequent reinfections, cardiovascular alterations, cognitive disabilities, declining physical functions, and poor quality of life. The phenomenon explains why so many patients who survive sepsis die sooner after hospital discharge than patients with other diseases or suffer from post-sepsis syndrome, immunosuppression ...

COVID-19 has had a significant impact since the pandemic was declared by WHO in 2020, with over 3 million deaths and counting, Researchers and medical teams have been hard at work at developing strategies to control the spread of the infection, caused by SARS-COV-2 virus and treat affected patients. Of special interest to the global population is the developments of vaccines to boost human immunity against SARS-COV-2, which are based on our understanding of how the viral proteins work during the infection in host cells. Two vaccines, namely the Pfizer/BioINtech and Oxford/AZ vaccine rely on the use of delivering the gene that encodes the viral spike protein either as an mRNA or through an adenovirus vector to promote the production of relevant antibodies. The use of monoclonal ...

In order to make meaningful gains in cardiovascular disease care, primary care medical practices should adopt a set of care improvements specific to their practice size and type, according to a new study from the national primary care quality improvement initiative EvidenceNOW. High blood pressure and smoking are among the biggest risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Primary care physicians help patients manage high blood pressure and provide smoking cessation interventions.

Researchers found that there is no one central playbook for all types of practices, but they did identify ...

Although new family medicine graduates intend to provide a broader scope of practice than their senior counterparts, individual family physicians' scope of practice has been decreasing, with fewer family physicians providing basic primary care services, such pediatric and prenatal care. Russell et al conducted a study to explore family medicine graduates' attitudes and perspectives on modifiable and non-modifiable factors that influenced their scope of practice and career choices. The authors conducted five focus group discussions with 32 family physicians and explored their attitudes and perspectives on their desired and actual scope of practice. Using a conceptual framework ...