Research team investigates causes of tuberous sclerosis

Mutations can disrupt protein binding through a "burr effect" thus interfering with the regulation of cell growth

2021-05-12

(Press-News.org) Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) affects between one and two of every 10,000 new-born babies. This genetic disease leads to the formation of benign tumours which can massively impair the proper functioning of vital organs such as the kidneys, the liver and the brain. The disease affects different patients to varying degrees and is triggered by mutations in one of two genes, the TSC1 or TSC2 gene. An interdisciplinary team of researchers led by biochemists Prof. Daniel Kümmel and Dr. Andrea Oeckinghaus from the University of Münster (Germany) examined the "tumour suppressor protein TSC1" and, for the first time, gained insights into its hitherto unclear functions. The team identified a new mechanism, in a central cellular process, which regulates cell growth. The results can also help in understanding how Tuberous Sclerosis Complex arises. The results of the study have now been published in the journal Molecular Cell (advance publication online).

Mutations concern a "burr effect"

The TSC1 protein and the TSC2 protein together form the TSC protein complex. This has the task of controlling cell growth and, as a result, of suppressing the emergence of tumours - hence the term "tumour suppressor". Previously, it had largely been unclear what the functions of TSC1 were. Similarly, little was known about the mechanism which is affected by certain mutations in the TSC1 gene in the occurrence of the disease. The researchers have now found out that one part of the TSC1 protein, a so-called domain, can bind to the surfaces of lysosomal membranes. Lysosomes are small compartments in the interior of the cell, surrounded by a membrane, which contain digestive enzymes. On their surface there are certain control centres which are important for the regulation of cell growth. The TSC1 protein ensures that the entire TSC complex arrives at these control centres and prevents any uncontrolled cell growth by inhibiting the activity of an important signal protein called "mTOR" - "Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin".

"In this process," Daniel Kümmel explains, "TSC1 uses a strategy reminiscent of the principle of the burr. The burr's individual hooks stick to material only very weakly, but lots of hooks together provide a firm attachment." The study shows that TSC1's individual membrane binding domain only forms a weak attachment. However, a strong attachment becomes possible with a controlled aggregation of a large number of TSC1 molecules. "Mutations occur particularly frequently in the membrane binding domain," says Andrea Oeckinghaus. "We assume that some of the pathogenic effects can now be explained by a loss of the correct localization of the TSC complex."

Membrane component regulates cell growth

Another discovery the team made is that the properties of the membrane surface can influence the way the TSC complex functions and, as a result, the growth processes in the cell. More precisely, the team identified a special component in the membrane: a lipid called phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI3,5P2), which is necessary for the activity of the TSC complex. Depending on how often it occurs on the membrane's surface, it has different effects on the activity. "As the production and breakdown of this lipid are regulated," says Daniel Kümmel, "this opens up entirely new perspectives on how cell growth can be controlled. This means that our results are an exciting starting point for further studies."

The team of researchers used a broad range of methods in its investigations, starting from approaches using structural biology and biochemistry, and also involving cell-biological experiments. "The resulting insights into mechanistic and physiological aspects were only possible through our interfaculty collaboration," says Kümmel.

The work was carried out jointly by the team headed by Dr. Andrea Oeckinghaus (Münster University Faculty of Medicine and Münster University Hospital, Institute of Molecular Tumour Biology) and the team led by Prof. Daniel Kümmel (Münster University Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy, Institute of Biochemistry). Important contributions were made by partners at the Max Planck Institute for the Biology of Ageing, Cologne (team headed by Dr. Constantinos Demetriades) and at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Physiology, Dortmund (team led by Prof. Stephan Raunser).

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-12

University of Cincinnati researchers studied the teeth of prehistoric horses and bison in the Arctic to learn more about their diets compared to modern species.

What they found suggests the Arctic 40,000 years ago maintained a broader diversity of plants that, in turn, supported both more -- and more diverse -- big animals.

The Arctic today is spartan compared to the wildlife-rich landscape during the ice ages of the Pleistocene epoch between 12,000 and 2.6 million years ago when wild horses, mammoths, bison and other big animals roamed the steppes and grasslands of what is now northern Canada, northern Europe, Alaska and Siberia. Short-faced bears, ground sloths and even cave lions called the 49th State home.

The Arctic supported greater populations ...

2021-05-12

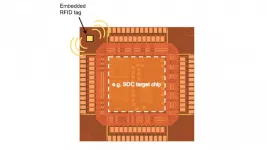

Researchers at North Carolina State University have made what is believed to be the smallest state-of-the-art RFID chip, which should drive down the cost of RFID tags. In addition, the chip's design makes it possible to embed RFID tags into high value chips, such as computer chips, boosting supply chain security for high-end technologies.

"As far as we can tell, it's the world's smallest Gen2-compatible RFID chip," says Paul Franzon, corresponding author of a paper on the work and Cirrus Logic Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at NC State.

Gen2 RFID chips are state of the art and are already in widespread use. One of the things that sets ...

2021-05-12

Meat that is certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is less likely to be contaminated with bacteria that can sicken people, including dangerous, multidrug-resistant organisms, compared to conventionally produced meat, according to a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The findings highlight the risk for consumers to contract foodborne illness--contaminated animal products and produce sicken tens of millions of people in the U.S. each year--and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms that, when they lead to illness, can complicate treatment.

The researchers found that, compared to conventionally processed meats, organic-certified meats were 56 percent less likely to be contaminated with ...

2021-05-12

Loss of smell, or anosmia, is one of the earliest and most commonly reported symptoms of COVID-19. But the mechanisms involved had yet to be clarified. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, Inserm, Université de Paris and the Paris Public Hospital Network (AP-HP) determined the mechanisms involved in the loss of smell in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 at different stages of the disease. They discovered that SARS-CoV-2 infects sensory neurons and causes persistent epithelial and olfactory nervous system inflammation. Furthermore, ...

2021-05-12

Many people live with chronic pain, and in some cases, cannabis can provide relief. But the drug also can significantly impact memory and other cognitive functions. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Medicinal Chemistry have developed a peptide that, in mice, allowed Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main component of Cannabis sativa, to fight pain without the side effects.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 20% of adults in the U.S. experienced chronic pain in 2019. Opioids, the mainstay for ...

2021-05-12

Alexandria, Va., USA -- COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 and given an incomplete understanding of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at that time, the American Dental Association recommended that dental offices refrain from providing non-emergency services. As a result, 198,000 dentists in the United States closed their doors to patients. The study "Sources of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Microorganisms in Dental Aerosols," published in the Journal of Dental Research (JDR), sought to inform infection-control science by identifying the source of bacteria and viruses in aerosol generating dental procedures.

Researchers at The Ohio State University College of Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, Columbus, USA, tracked the origins of microbiota in aerosols generated during treatment ...

2021-05-12

Are you empathic, generous and altruistic? In short, do you possess that specific personality trait defined as agreeableness in the language of psychologists? New research from SISSA recently published in the journal NeuroImage sheds light on brain mechanisms underlying this trait.

The study showed that detached and individualistic subjects seem to process information associated with social and non-social contexts in similar ways, as demonstrated by similar activation patterns in the prefrontal cortex, whereas in more agreeable subjects the activation patterns ...

2021-05-12

Peri-implantitis, a condition where tissue and bone around dental implants becomes infected, besets roughly one-quarter of dental implant patients, and currently there's no reliable way to assess how patients will respond to treatment of this condition.

To that end, a team led by the University of Michigan School of Dentistry developed a machine learning algorithm, a form of artificial intelligence, to assess an individual patient's risk of regenerative outcomes after surgical treatments of peri-implantitis.

The algorithm is called FARDEEP, which stands for Fast and Robust Deconvolution of Expression ...

2021-05-12

When Museums closed their doors in March 2020 for the first COVID-19 lockdown in the UK a majority moved their activities online to keep their audiences interested. Researchers from WMG, University of Warwick have worked with OUMNH, to analyse the success of the exhibitions, and say the way Museums operate will change forever.Caption: Compton Verney's homepage for the Cranach exhibition which opened in March 2020 Credit: Compton Verney

The cultural impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been analysed by researchers from WMG, University of Warwick in collaboration with OUMNH (Oxford University Museum of Natural History) who in the paper, 'Digital Responses ...

2021-05-12

An international research team led by the University of Cologne has succeeded for the first time in connecting several atomically precise nanoribbons made of graphene, a modification of carbon, to form complex structures. The scientists have synthesized and spectroscopically characterized nanoribbon heterojunctions. They then were able to integrate the heterojunctions into an electronic component. In this way, they have created a novel sensor that is highly sensitive to atoms and molecules. The results of their research have been published under the title 'Tunneling current modulation in atomically precise graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions' in Nature Communications. The work was carried out in close cooperation between the Institute for ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research team investigates causes of tuberous sclerosis

Mutations can disrupt protein binding through a "burr effect" thus interfering with the regulation of cell growth