(Press-News.org) University of Massachusetts Amherst neuroscientists examining genetically identified neurons in a songbird's forebrain discovered a remarkable landscape of physiology, auditory coding and network roles that mirrored those in the brains of mammals.

The research, published May 13 in Current Biology, advances insight into the fundamental operation of complex brain circuits. It suggests that ancient cell types in the pallium - the outer regions of the brain that include cortex - most likely retained features over millions of years that are the building blocks for advanced cognition in birds and mammals.

"We as neuroscientists are catching on that birds can do sophisticated things and they have sophisticated circuits to do those things," says behavioral neuroscientist Luke Remage-Healey, associate professor of psychological and brain sciences and senior author of the paper.

For the first time, the team of neuroscientists, including lead author Jeremy Spool, who worked as a National Institutes of Health (NIH) postdoctoral fellow in Remage-Healey's lab, used viral optogenetics to define the molecular identities of excitatory and inhibitory cell types in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) and match them to their physiological properties.

"In the songbird community, we've had a hunch for a long time that when we record the electrical signatures of these two cell types, we say - 'that's a putative excitatory neuron, that's a putative inhibitory neuron.' Now we know that these features are grounded in molecular truth," Remage-Healey says. "Without being able to pinpoint the cell types with these viruses, we wouldn't be able to learn how the cell and network features bear resemblance to those in mammals, because the brain architectures are so different."

The research team used viruses from a collection curated by co-author Yoko Yazaki-Sugiyama at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan to conduct viral optogenetic experiments in the brain. With optogenetics, the team used flashes of light to manipulate one cell type independent of the other. The team targeted excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons (using CaMKIIα and GAD1 promoters, respectively) in the zebra finch auditory pallium to test predictions based on the mammalian pallium.

"There's so much work out there on the physiology of these different cell types in the mammalian cortex that we were able to line up a series of predictions about what features birds may or may not have," Spool says.

The CaMKIIα and GAD1 populations in the songbird were distinct "in exactly the proportions you would expect from the mammalian brain," Spool says. With the cell type populations isolated, the researchers then examined systematically whether each population would correspond to the physiology of their mammalian counterparts.

"As we kept moving forward, again and again these cell populations were acting as if they were essentially from the mammalian cortex in a lot of physiological ways," Spool says.

Remage-Healey adds, "The correspondence between the cortex in mammals and what we're pulling out with molecularly identified cell types in birds is pretty striking."

In both birds and mammals, these neurons are thought to support advanced cognitive functions, such as memory, individual recognition and associative learning, Spool says.

Remage-Healey says the research, supported by NIH grants, helps delineate "the basic nuts and bolts of how the brain operates." Knowing the nuts and bolts builds foundations necessary to develop breakthroughs that could lead to neurological interventions for brain disorders.

"This can help us figure out what brain diversity is out there by unpacking these circuits and the ways they can go awry," Remage-Healey says.

INFORMATION:

The Antarctic ice sheet was even more unstable in the past than previously thought, and at times possibly came close to collapse, new research suggests.

The findings raise concerns that, in a warmer climate, exposing the land underneath the ice sheet as it retreats will increase rainfall on Antarctica, and this could trigger processes that accelerate further ice loss.

The research is based on climate modelling and data comparisons for the Middle Miocene (13-17 million years ago) when atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperatures reached levels similar to those expected by the end of this century.

The study was carried out by ...

A new discovery led by Princeton University could upend our understanding of how electrons behave under extreme conditions in quantum materials. The finding provides experimental evidence that this familiar building block of matter behaves as if it is made of two particles: one particle that gives the electron its negative charge and another that supplies its magnet-like property, known as spin.

"We think this is the first hard evidence of spin-charge separation," said Nai Phuan Ong, Princeton's Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics and senior author on the paper published this week in the journal Nature Physics.

The experimental results fulfill a prediction made decades ago to explain one of the most mind-bending states ...

The chemical compound glyphosate, the world's most widely used herbicide, can weaken the immune systems of insects, suggests a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Round Up™, a popular U.S. brand of weed killer products.

The researchers investigated the effects of glyphosate on two evolutionarily distant insects, Galleria mellonella, the greater wax moth, and Anopheles gambiae, a mosquito that is an important transmitter of malaria to humans in Africa. They found that ...

People who work nontraditional work hours, such as 11 p.m.-7 p.m., or the "graveyard" shift, are more likely than people with traditional daytime work schedules to develop a chronic medical condition -- shift work sleep disorder -- that disrupts their sleep. According to researchers at the University of Missouri, people who develop this condition are also three times more likely to be involved in a vehicle accident.

"This discovery has many major implications, including the need to identify engineering counter-measures to help prevent these crashes from happening," said Praveen Edara, department chair and professor of civil and environmental ...

Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, a trio of science communication researchers proposes to treat the Covid-19 misinformation "infodemic" with the same methods used to halt epidemics.

"We believe the intertwining spreads of the virus and of misinformation and disinformation require an approach to counteracting deceptions and misconceptions that parallels epidemiologic models by focusing on three elements: real-time surveillance, accurate diagnosis, and rapid response," the authors write in a Perspective article.

"The word 'communicable' comes from the Latin communicare, ...

New research led by the University of Kent has found that people fail to recognise the role of factory farming in causing infectious diseases.

The study published by Appetite demonstrates that people blame wild animal trade or lack of government preparation for epidemic outbreaks as opposed to animal agriculture and global meat consumption.

Scientists forewarned about the imminence of global pandemics such as Covid-19, but humankind failed to circumvent its arrival. They had been warning for decades about the risks of intensive farming practices for public health. The scale of production and overcrowded conditions on factory farms make it easy for viruses to migrate and spread. Furthermore, ...

HOUSTON - Cytokine-activated natural killer (NK) cells derived from donated umbilical cord blood, combined with an investigational bispecific antibody targeting CD16a and CD30 known as AFM13, displayed potent anti-tumor activity against CD30+ lymphoma cells, according to a new preclinical study from researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The findings were published today in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. These results led to the launch of a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the combination of cord blood-derived NK cells (cbNK cells) with AFM13 as an experimental cell-based immunotherapy in patients with CD30+ lymphoma.

"Developing novel NK cell therapies has been a priority for my ...

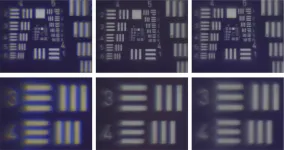

WASHINGTON -- In a new study, researchers have shown that 3D printing can be used to make highly precise and complex miniature lenses with sizes of just a few microns. The microlenses can be used to correct color distortion during imaging, enabling small and lightweight cameras that can be designed for a variety of applications.

"The ability to 3D print complex micro-optics means that they can be fabricated directly onto many different surfaces such as the CCD or CMOS chips used in digital cameras," said Michael Schmid, a member of the research team from University of Stuttgart in Germany. "The micro-optics can ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Free from human disturbance for a century, an inland island in Central America has nevertheless lost more than 25% of its native bird species since its creation as part of the Panama Canal's construction, and scientists say the losses continue.

The Barro Colorado Island extirpations show how forest fragmentation can reduce biodiversity when patches of remnant habitat lack connectivity, according to a study by researchers at Oregon State University.

Even when large remnants of forest are protected, some species still fail to survive because of subtle ...

DALLAS - May 12, 2021 - Scientists with UT Southwestern's Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute have identified the molecular mechanism that can cause weight gain for those using a common antipsychotic medication. The findings, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, suggest new ways to counteract the weight gain, including a drug recently approved to treat genetic obesity, according to the study, which involved collaborations with scientists at UT Dallas and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

"If this effect can be shown in clinical trials, it could give us a way to effectively treat ...