(Press-News.org) The first frost of autumn may be grim for gardeners but the latest evidence reveals it is a profound event in the life of plants.

The discovery may affect how we grow crops in a fluctuating climate and help us better understand molecular mechanisms in animals and humans.

Much of our understanding of how plants register temperature at a molecular level has been gained from the study of vernalization - the exposure to an extended period of cold as a preparation for flowering in spring.

Experiments using the model plant Arabidopsis have shown how this prolonged period of cold lifts the brake on flowering, a gene called FLC. This biochemical brake also involves another molecule COOLAIR which is antisense to FLC. This means it lies on the other strand of DNA to FLC and it can bind to FLC and influence its activity.

But less is known about how natural temperature changes affect this process. How does COOLAIR facilitate the shutdown of FLC in nature?

To find out, researchers from the John Innes Centre used naturally occurring types of Arabidopsis grown in different climates.

They measured how much COOLAIR is turned on in three different field sites with varying winter conditions, one in Norwich, UK, one in south Sweden and one in subarctic northern Sweden.

COOLAIR levels varied among different accessions and different locations. However, researchers spotted something that all the plants had in common - the first time the temperature dropped below freezing there was a peak in COOLAIR.

To confirm this boosting of COOLAIR after freezing they did experiments in temperature-controlled chambers which simulated the temperature changes seen in natural conditions.

They found COOLAIR expression levels rose within an hour of freezing and peaked about eight hours afterwards. There was a small reduction in FLC levels immediately after freezing too, reflecting the relationship between the two key molecular components.

Next, they found a mutant Arabidopsis which produces higher levels of COOLAIR all the time even when it is not cold, and low levels of FLC. When they edited the gene to switch off COOLAIR they found that FLC was no longer suppressed, providing further evidence of this elegant molecular mechanism.

Dr Yusheng Zhao, co-first author of the study said: "Our study shows a new aspect of temperature sensing in plants in natural field conditions. The first seasonal frost serves as an important indicator in autumn for winter arrival. The initial freezing dependent induction of COOLAIR appears to be an evolutionarily conserved feature in Arabidopsis and helps to explain how plants sense environmental signals to begin silencing of the major floral repressor FLC to align flowering with spring."

The study offers insight into the plasticity in the molecular process of how plants sense temperatures which may help plants adapt to different climates.

Professor Dame Caroline Dean, corresponding author of the study explained: "From the plant's point of view it gives you a tunable way of shutting off FLC. Any modulation of antisense will switch off sense and from an evolutionary perspective, depending on how efficiently or how fast this happens, and how many cells it happens in, you then have a way of dialing the brake up and down among cells."

The findings will be helpful for understanding how plants and other organisms sense fluctuating environmental signals and could be translatable to improving crops at a time of climate change.

The discovery will also likely be widely relevant for environmental regulation of gene expression in many organisms because antisense transcription has been shown to alter transcription in yeast and human cells.

INFORMATION:

The study: Natural temperature fluctuations promote COOLAIR regulation of FLC appears in Genes & Development.

Researchers at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) have identified gaps in patient knowledge about pain management and opioid use before total hip replacement, including misconceptions about how much pain relief to expect from opioids after surgery, how to use multiple modes of pain relief (multimodal analgesia) safely and effectively, and proper opioid storage and disposal. These findings were presented at the 2021 Spring American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) Annual Meeting.1

"Patients who are not taught about opioids and pain management may have difficulty with pain control and worse functional outcomes after total ...

Researchers at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) have identified risk factors for persistent opioid use after surgery in pediatric patients.1 Study findings were presented at the 2021 Spring American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) Annual Meeting.

Previous research indicates that prescription patterns for opioids after surgery in children and adolescents may be associated with long-term use and abuse.2

"Pediatric patients have developing brains that are uniquely vulnerable to addiction, and we need to learn to treat their pain safely without putting them at additional ...

In a study carried out in mice at the University of Chicago, researchers found that lasofoxifene outperformed fulvestrant, the current gold-standard drug, in reducing or preventing primary tumor growth. It also was more effective at preventing metastasis in the lung, liver, bone and brain, the four most common areas for this cancer to spread.

Additionally, while fulvestrant and similar drugs often cause unwanted, menopausal-like side effects, lasofoxifene prevents some of these symptoms. The research was published on May 13 in END ...

How people consume news and take actions based on what they read, hear or see, is different than how human brains process other types of information on a daily basis, according to researchers at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. While the current state of the newspaper industry is in flux, these journalism experts discovered people still love reading newspapers, and they believe a newspaper's physical layout and structure could help curators of digital news platforms enhance their users' experiences.

"Many people still love print newspapers, and to an extent, we also see that they like the digital replicas of print newspapers as much as they do the physical version," said Damon Kiesow, a professor of journalism professions and co-author on the study. "But we believe there ...

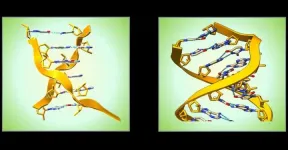

In a paper published in the May 13th, 2021 issue of PLOS Genetics, a Z-RNA nanoswitch that regulates interferon immune responses is described. The switch, less than 5 nanometer in length, is based on sequences, called flipons, that change outcomes by altering their three dimensional conformation. The Z-RNA nanoswitch flips from the shorter right-handed A-RNA helix ("on") to the longer left-handed Z-RNA helix ("off"). The flip ends immune responses against self RNAs, but not against viruses. Surprisingly, the Z-RNA nanoswitch sequence is encoded by "junk DNA". The Z-RNA nanoswitch is used by some cancers to silence anti-tumor immune responses. In other cases, a malfunction of the Z-RNA nanoswitch causes inflammatory disease.

In the ...

A new strategy for capturing the 3D shape of the human face draws on data from sibling pairs and leads to identification of novel links between facial shape traits and specific locations within the human genome. Hanne Hoskens of the Department of Human Genetics at Katholieke Universiteit in Leuven, Belgium, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Genetics.

The ability to capture the 3D shape of the human face--and how it varies between individuals with different genetics--can inform a variety of applications, including understanding human evolution, planning for surgery, and forensic sciences. ...

Mutations in two genetic regions in dogs explain over one third of the risk of developing an aggressive form of hematological cancer, according to a study led by Jacquelyn Evans and Elaine Ostrander at the National Human Genome Research Institute in Maryland, USA and colleagues. The study, which combined multiple sequencing techniques to investigate histiocytic sarcoma in retriever dogs, publishes May 13 in the open-access journal PLOS Genetics.

Histiocytic sarcoma is an aggressive cancer of immune cells, and although extremely rare in humans, it affects around one-in-five flat-coated retrievers. Genome-wide association surveys of 177 affected and 132 unaffected flat-coated ...

A new whole genome sequence for the Yap hadal snailfish provides insights into how the unusual fish survives in some of the deepest parts of the ocean. Xinhua Chen of the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University and Qiong Shi of the BGI Academy of Marine Sciences published their analysis of the new genome May 13th in the journal PLOS Genetics.

Animals living in deep-sea environments face many challenges, including high pressures, low temperatures, little food and almost no light. Fish are the only animals with a backbone that live in the hadal zone--defined as depths below 6,000 meters--and hadal snailfishes live in at least five separate marine trenches. Chen, Shi and their colleagues constructed a high-quality whole genome sequence from the Yap ...

Artificial intelligence (AI) learning machines can be trained to solve problems and puzzles on their own instead of using rules that we made for them. But often, researchers do not know what rules the machines make for themselves. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Assistant Professor Peter Koo developed a new method that quizzes a machine-learning program to figure out what rules it learned on its own and if they are the right ones.

Computer scientists "train" an AI machine to make predictions by presenting it with a set of data. The machine extracts a series of rules and operations--a model--based on information it encountered during its training. Koo says:

"If you learn general ...

QUT air-quality expert Distinguished Professor Lidia Morawska is leading an international call for a "paradigm shift" in combating airborne pathogens such as COVID-19, demanding universal recognition that infections can be prevented by improving indoor ventilation systems.

Professor Morawska led a group of almost 40 researchers from 14 countries in a call published in Science for a shift in standards in ventilation requirements equal in scale to the transformation in the 1800s when cities started organising clean water supplies and centralised sewage systems.

The international group of air quality researchers called on the World ...