How moths find their flame - genetics of mate attraction discovered

Biologists have discovered the gene controlling the mating preference of male European corn borer moths for the female sex pheromone

2021-05-14

(Press-News.org) The mysteries of sexual attraction just became a little less mysterious - at least for moths. A team of six American and European research groups including Tufts University has discovered which gene expressed in the brain of the male European corn borer moth controls his preference for the sex pheromone produced by females. This complements a previous study on the gene expressed in the female pheromone gland that dictates the type of blend she emits to attract males. The study was reported today in Nature Communications.

The implications go beyond making a better dating app for bugs. Now scientists can begin to ask why mating signals and mating preferences change in the first place, which is a long-standing paradox since any change could reduce the ability of an organism to successfully mate. Knowledge of these two genes will provide a better understanding of how the pheromones of the 160,000 moth species have evolved.

Of course, one important role for mating preferences is to make sure you are not matching up with a completely different species. The signal sent by females must be preferred by males of the same species to ensure that like mates with like--a mechanism called assortative mating. The European corn borer is interesting because there are two types, called E and Z, with assortative mating within each type. Even though the two types can be mated to each other in captivity, E mostly mates with E, and Z with Z in the field. For this reason, the European corn borer has been used as a model for how one species can split into two, ever since the two pheromone types were first discovered 50 years ago.

"That means we now know - at the molecular level - how chemical matchmaking aids in the formation of new species. Similar genetic changes to pheromone preference could help explain how tens of thousands of other moth species remain separate," said Erik Dopman, professor of biology in the School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts and corresponding author of the study.

Different aspects of the research were conducted by the three co-first authors Fotini Koutroumpa of University of Amsterdam, Melanie Unbehend of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, and Genevieve Kozak, a former post-doctoral scholar at Tufts University and now assistant professor at University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. "Our study's success can be attributed to a team with a common vision and strong sense of humor that helped make the science worthwhile and fun," said Dopman.

One of the surprise discoveries made by the team was that while females may vary their signals in the blend of pheromones they produce, preference in the male is driven by a protein that changes their brain's neuronal circuitry underlying detection rather than affecting the receptors responsible for picking up the pheromones.

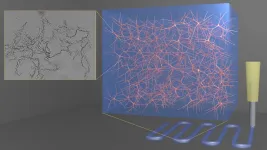

Preference for a particular cocktail of pheromones is determined by any of hundreds of variants found within the bab gene of the male. The relevant variants of bab are not in parts of the gene that code for a protein, but in parts that likely determine how much of the protein is produced, which in turn affects the neuronal circuits running from the antennae to the brain. The researchers were able to determine anatomical differences in the male, including the reach of olfactory sensory neurons into different parts of the moth brain, and link them to their attraction to E or Z females.

"This is the first moth species out of 160,000 in which female signalling and male preference genes have both been identified," said Astrid Groot of the University of Amsterdam, who also helped identify the gene controlling the pheromone difference in E and Z females. "That provides us with complete information on the evolution of mate choice and a way to measure how closely these choices are linked to evolving traits and populations."

The ability to predict mating could also help control reproduction in pest insects. The European corn borer is a significant pest for many agricultural crops in addition to corn. In the U.S., it costs nearly $2 billion each year to monitor and control. It is also the primary pest target for genetically modified "Bt corn" which expresses insecticidal proteins derived from the bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis. While Bt corn remains an effective control of the corn borer moth in the U.S., corn borers in Nova Scotia are now evolving resistance to another variety of Bt corn.

"Our results can help to predict whether Bt resistance could spread from Nova Scotia to the Corn Belt of the U.S., or whether assortative mating could prevent or delay it", said co-author David Heckel at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, who also studies how insects evolve resistance to Bt. "Bt corn has enabled a huge reduction in the use of chemical insecticides, and it should be a high priority to preserve its ecological benefits as long as possible."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-14

3D-printable gels with improved and highly controlled properties can be created by merging micro- and nano-sized networks of the same materials harnessed from seaweed, according to new research from North Carolina State University. The findings could have applications in biomedical materials - think of biological scaffolds for growing cells - and soft robotics.

Described in the journal Nature Communications, the findings show that these water-based gels - called homocomposite hydrogels - are both strong and flexible. They are composed of alginates - chemical compounds found in seaweed and algae that are commonly used as thickening agents and in wound ...

2021-05-14

Scientists at UCL have identified a new immunotherapy to combat the hepatitis B virus (HBV), the most common cause of liver cancer in the world.

Each year, globally, chronic HBV causes an estimated 880,000 deaths from liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma/liver cancer (HCC).

The pioneering study used immune cells isolated directly from patient liver and tumour tissue, to show that targeting acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), an enzyme that helps to manage cholesterol levels in cells*, was highly effective at boosting immune ...

2021-05-14

Researchers at the University of Bristol found that plant eaters diversified quickly after mass extinctions to eat different kinds of plants, and the ones that were able to chew harsher materials, which reflected the drying conditions of the late Triassic, became the most successful. These tougher herbivores included some of the first dinosaurs.

Following the largest mass extinction of all time, the end-Permian mass extinction, ecosystems rebuilt from scratch during Triassic times, from 252-201 million years ago paving the way for new species, and many new kinds of plants and animals emerged. In a new study published in Nature Communications and led by Dr Suresh Singh of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences, fresh ...

2021-05-14

A new study led by University of Liverpool researchers has confirmed that children with cystic fibrosis (CF) in the US have better lung function than UK children with the disease.

The study suggests that differences do not appear to be explained by early growth or nutrition, but could be linked to differences in the use of early treatments.

This long-term analysis follows a 2015 study comparing UK and CF populations in the year 2010, which first highlighted potential differences in lung function.

CF is a serious, multi-organ inherited disease characterised by pulmonary infections and progressively declining lung function. Most people ...

2021-05-14

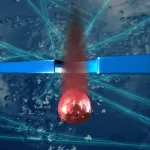

Osaka, Japan - Scientists from the Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research at Osaka University used machine learning methods to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio in data collected when tiny spheres are passed through microscopic nanopores cut into silicon substrates. This work may lead to much more sensitive data collection when sequencing DNA or detecting small concentrations of pathogens.

Miniaturization has opened the possibility for a wide range of diagnostic tools, such as point-of-care detection of diseases, to be performed quickly and with very small samples. For example, unknown particles can be analyzed by passing ...

2021-05-14

The primary cilium, an antenna-like subcellular structure ('organelle') protruding from the outside of many types of vertebrate cells, has an important but previously overlooked role in guiding the growth of lymphatic vessels, shows a new study. The authors show for the first time that mouse and human lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) - which make up the inner and outer lining of lymphatic vessels - use primary cilia. They find that LEC primary cilia may direct the growth of a functional lymphatic network, not only during prenatal development, but also throughout life during inflammation and wound healing and in response to cancer. They show that mice in which the formation of primary cilia in LECs is prevented develop lymphatic ...

2021-05-14

Bethesda, MD (May 14, 2021) -- Daily probiotic use was associated with fewer upper respiratory symptoms in overweight and older people, according to a study that suggests a potential role for probiotics in preventing respiratory infections. The study was selected for presentation at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2021.

"This is not necessarily the most intuitive idea, that putting bacteria into your gut might reduce your risk of respiratory infection," said Benjamin Mullish, MD, a lead researcher on the study and clinical lecturer in the Division of Digestive Diseases, Imperial College London, England, "but it's further ...

2021-05-14

Bethesda, MD (May 14, 2021) -- Despite the fact that certain racial and ethnic minorities get pancreatic cancer more often, are diagnosed at a younger age and die sooner, clinical trials fail to include representative proportions of non-White patients at every phase of study, according to research that was selected for presentation at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2021.

"We see disparities in representation across all kinds of clinical trials, so we were not surprised to see that it also occurs in pancreatic cancer trials. But hopefully we can make a change in that arena in the future," said Kelly Herremans, MD, lead researcher on the study and surgical research fellow at the University ...

2021-05-14

Bethesda, MD (May 14, 2021) -- Combining minimally invasive endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) with the diabetes drug semaglutide can provide additional significant weight loss for patients who are not candidates for invasive weight-loss surgery, according to research that was selected for presentation at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2021.

"As the worldwide obesity rate continues to climb, so do the number of people seeking bariatric surgery to treat their condition," said Anna Carolina Hoff, MD, lead researcher on the study and founder and clinical director of Angioskope Brazil, São José dos Campos. "Surgical procedures are some of the most successful ways to help patients lose weight, but they ...

2021-05-14

Bethesda, MD (May 14, 2021) -- Inpatient consults for alcohol-related gastrointestinal (GI) and liver diseases have surged since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and remained elevated, according to research selected for presentation at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2021. The proportion of patients that required inpatient endoscopic interventions for their alcohol-related GI and liver diseases has also increased, highlighting an apparent worsening trend in the severity of disease.

"When we went into lockdown, many people experienced significant negative ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How moths find their flame - genetics of mate attraction discovered

Biologists have discovered the gene controlling the mating preference of male European corn borer moths for the female sex pheromone