(Press-News.org) Three billion years ago, light first zipped through chlorophyll within tiny reaction centers, the first step plants and photosynthetic bacteria take to convert light into food.

Heliobacteria, a type of bacteria that uses photosynthesis to generate energy, has reaction centers thought to be similar to those of the common ancestors for all photosynthetic organisms. Now, a University of Michigan team has determined the first steps in converting light into energy for this bacterium.

"Our study highlights the different ways in which nature has made use of the basic reaction center architecture that emerged over 3 billion years ago," said lead author and U-M physicist Jennifer Ogilvie. "We want to ultimately understand how energy moves through the system and ends up creating what we call the 'charge-separated state.' This state is the battery that drives the engine of photosynthesis."

laser 2.jpegPhotosynthetic organisms contain "antenna" proteins that are packed with pigment molecules to harvest photons. The collected energy is then directed to "reaction centers" that power the initial steps that convert light energy into food for the organism. These initial steps happen on incredibly fast timescales--femtoseconds, or one millionth of one billionth of a second. During the blink of an eye, this conversion happens many quadrillions of times.

Researchers are interested in understanding how this transformation takes place. It gives us a better understanding of how plants and photosynthetic organisms convert light into nourishing energy. It also gives researchers a better understanding of how photovoltaics work--and the basis for understanding how to build them better.

When light hits a photosynthetic organism, pigments within the antenna gather photons and direct the energy toward the reaction center. In the reaction center, the energy bumps an electron to a higher energy level, from which it moves to a new location, leaving behind a positive charge. This is called a charge separation. This process happens differently based on the structure of the reaction center in which it occurs.

In the reaction centers of plants and most photosynthetic organisms, the pigments that orchestrate charge separation absorb similar colors of light, making it difficult to visualize charge separation. Using the heliobacteria, the researchers identified which pigments initially donate the electron after they're excited by a photon, and which pigments accept the electron.

Heliobacteria is a good model to examine, Ogilvie said, because their reaction centers have a mixture of chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll, which means that these different pigments absorb different colors of lights. For example, she said, imagine trying to follow a person in a crowd--but everyone is wearing blue jackets, you're watching from a distance and you can only take snapshots of the person moving through the crowd.

"But if the person you were watching was wearing a red jacket, you could follow them much more easily. This system is kind of like that: It has distinct markers," said Ogilvie, professor of physics, biophysics, and macromolecular science and engineering

Previously, heliobacteria were difficult to understand because its reaction center structure was unknown. The structure of membrane proteins like reaction centers are notoriously difficult to determine, but Ogilvie's co-author, Arizona State University biochemist Kevin Redding, developed a way to resolve the crystal structure of these reaction centers.

To probe reaction centers in heliobacteria, Ogilvie's team uses a type of ultrafast spectroscopy called multidimensional electronic spectroscopy, implemented in Ogilvie's lab by lead author and postdoctoral fellow Yin Song. The team aims a sequence of carefully timed, very short laser pulses at a sample of bacteria. The shorter the laser pulse, the broader light spectrum it can excite.

Each time the laser pulse hits the sample, the light excites the reaction centers within. The researchers vary the time delay between the pulses, and then record how each of those pulses interacts with the sample. When pulses hit the sample, its electrons are excited to a higher energy level. The pigments in the sample absorb specific wavelengths of light from the laser--specific colors--and the colors that are absorbed give the researchers information about the energy level structure of the system and how energy flows through it.

"That's an important role of spectroscopy: When we just look at the structure of something, it's not always obvious how it works. Spectroscopy allows us to follow a structure as it's functioning, as the energy is being absorbed and making its way through those first energy conversion steps," Ogilvie said. "Because the energies are quite distinct in this type of reaction center, we can really get an unambiguous look at where the energy is going."

Getting a clearer picture of this energy transport and charge separation allows the researchers to develop more accurate theories about how the process works in other reaction centers.

"In plants and bacteria, it's thought that the charge separation mechanism is different," Ogilvie said. "The dream is to be able to take a structure and, if our theories are good enough, we should be able to predict how it works and what will happen in other structures--and rule out mechanisms that are incorrect."

INFORMATION:

Study: END

May 14, 2021 - Two thirds of all pediatric spinal fractures, especially in the adolescent population, occur in motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) where seatbelts are not utilized, reports a study in Spine. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Over 60 percent of pediatric spinal fractures occur in children ages 15 to 17, coinciding with the beginning of legal driving," according to the new research by Dr. Vishal Sarwahi, MD, of Cohen Children's Medical Center, New Hyde Park, NY, and colleagues. They emphasize the need for measures to increase seatbelt usage, particularly by younger drivers, and outline the potential trauma that can be avoided through proper seatbelt use.

Seatbelts save lives... and ...

May 14, 2021 - Two years ago, the Veterans Affairs healthcare system (VA) began rolling out a new benefit, enabling Veterans to receive urgent care from a network of community providers - rather than visiting a VA emergency department or clinic. Progress toward expanding community care services for Veterans is the focus of a special supplement to the May issue of Medical Care. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The urgent care benefit "provides a new way to deliver unscheduled, low-acuity acute care to Veterans," according to the ...

A team led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and Children's National Hospital has developed a unique pre-clinical model that enables the study of long-term HIV infection, and the testing of new therapies aimed at curing the disease.

Ordinary mice cannot be infected with HIV, so previous HIV mouse models have used mice that carry human stem cells or CD4 T cells, a type of immune cell that can be infected with HIV. But these models tend to have limited utility because the human cells soon perceive the tissues of their mouse hosts as "foreign," ...

The question of why we dream is a divisive topic within the scientific community: it's hard to prove concretely why dreams occur and the neuroscience field is saturated with hypotheses. Inspired by techniques used to train deep neural networks, Erik Hoel (@erikphoel), a research assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts University, argues for a new theory of dreams: the overfitted brain hypothesis. The hypothesis, described May 14 in a review in the journal Patterns, suggests that the strangeness of our dreams serves to help our brains better generalize our day-to-day experiences.

"There's obviously an incredible number of theories of why we dream," says Hoel. "But I wanted to bring to ...

Rodents and pigs share with certain aquatic organisms the ability to use their intestines for respiration, finds a study publishing May 14th in the journal Med. The researchers demonstrated that the delivery of oxygen gas or oxygenated liquid through the rectum provided vital rescue to two mammalian models of respiratory failure.

"Artificial respiratory support plays a vital role in the clinical management of respiratory failure due to severe illnesses such as pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome," says senior study author Takanori Takebe (@TakebeLab) of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University and the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. "Although the side effects and safety need to be thoroughly ...

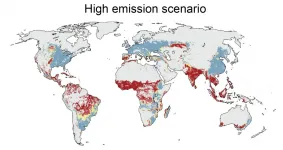

Climate change is known to negatively affect agriculture and livestock, but there has been little scientific knowledge on which regions of the planet would be touched or what the biggest risks may be. New research led by Aalto University assesses just how global food production will be affected if greenhouse gas emissions are left uncut. The study is published in the prestigious journal One Earth on Friday 14 May.

'Our research shows that rapid, out-of-control growth of greenhouse gas emissions may, by the end of the century, lead to more than a third of current global food production falling into conditions in which no food is produced today - that is, out of safe climatic space,' explains Matti Kummu, professor of global water and food issues at Aalto University.

According ...

What The Study Did: Researchers analyzed changes in filled prescriptions for naloxone (medication to reverse opioid overdoses) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and compared them with changes in opioid prescriptions and overall prescriptions.

Authors: Ashley L. O'Donoghue, Ph.D., of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0393)

Editor's Note: The ...

What The Study Did: Associations of staffing and testing interventions with COVID-19 transmission in nursing homes are examined in this decision analytical modeling study.

Authors: Rebecca Kahn, Ph.D., of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10071)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

What The Study Did: This is a qualitative study that evaluates a crowdsourcing open call to gather community input for engaging the university community in COVID-19 safety strategies.

Authors: Suzanne Day, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10090)

Editor's Note: This article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the compliance of hospitals with a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ruling mandating that a list of charges for services, procedures and items be publicly available and in a machine-readable file.

Authors: David Hsiehchen, M.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...