(Press-News.org) Early preterm births may be dramatically decreased with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplements, with a dose of 1000 mg more effective for pregnant women with low DHA levels than the 200 mg found in some prenatal supplements, according to a study led by researchers from the University of Kansas and the University of Cincinnati and published today in EClinicalMedicine, a clinical journal of The Lancet. Early preterm birth, defined as birth before 34 weeks gestation, is a serious public health issue because these births result in the highest risk of infant mortality and child disability.

"This study tells us that pregnant women should be taking DHA," said Susan E. Carlson, Ph.D., professor of nutrition in the Department of Dietetics and Nutrition in the KU School of Health Professions, co-principal investigator and first author on the study. "And many would benefit from a higher amount than in some prenatal supplements, particularly if they are not already taking a prenatal vitamin with at least 200 mg DHA or eating seafood or eggs regularly," Carlson said. "Many pregnant women take DHA, but we wanted to see if the amount in most prenatal supplements was enough to prevent early preterm birth."

Overall, women who received the higher dose had fewer early preterm birth, however, participants with low DHA levels at enrollment had half the rate of early preterm birth (2.0% compared to 4.1%) when they were given a supplement of 1000 mg compared with those given a 200 mg supplement during the last half of pregnancy. For women who began the study with high DHA levels, many of whom were already taking prenatal DHA, the rate of early preterm birth was 1.3%, and there was no benefit of the higher dose.

"We knew from our previous work that women in the United States eat very little food sources of DHA, and we thought a higher dose might be needed to boost intake," said Christina J. Valentine, M.D., a neonatologist and registered dietitian at the University of Cincinnati and one of three principal investigators for the study.

Because preterm birth is associated with such negative outcomes and high health care costs, having an option for women to prevent preterm birth reliably and inexpensively is significant.

"This study is a potential game changer for obstetricians and their patients," said co-author Carl P. Weiner, M.D., professor of obstetrics and gynecology and professor of integrative and molecular physiology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine and professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Kansas School of Pharmacy. "The dramatic decrease in early preterm birth with DHA supplementation will improve short- and long -term outcomes for children, families and society in a cost-effective fashion."

Carlson notes that this information should be widely shared with women who are pregnant and those planning to become pregnant. "Women should be consulting with their doctor and getting their DHA levels tested to ensure they are taking the proper dose to prevent preterm birth," she said.

The multi-center, double-blind, randomized, superiority trial recruited participants at three large academic medical centers in the United States (the University of Kansas Medical Center, Ohio State University and the University of Cincinnati).

The study used an innovative Bayesian response adaptive randomization design developed by Byron J Gajewski Ph.D., a professor in the department of Biostatistics & Data Science in the KU School of Medicine and one of three principal investigators on the study. "The study design allowed us to preserve the rigor of the study while allowing us to more efficiently work to accomplish the study goals," he said. One example of that, Gajewski said, is that once one arm of the study showed more success, future enrollees were more likely to be placed into that arm. "People enrolling the participants don't see behind the scenes, but the statisticians are able to use this technique to more efficiently get to the answers the study is seeking."

INFORMATION:

The principal investigators who designed and led the study were Susan E. Carlson Ph.D., of the University of Kansas Medical Center and KU Life Span Institute; Byron J. Gajewski Ph.D., of the University of Kansas Medical Center; and Christina J. Valentine M.D., of the University of Cincinnati.

Funding for the study was providing by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

PITTSBURGH, May 17, 2021 - Monoclonal antibodies, a COVID-19 treatment given early after coronavirus infection, cut the risk of hospitalization and death by 60% in those most likely to suffer complications of the disease, according to an analysis of UPMC patients who received the medication compared to similar patients who did not.

UPMC and University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine physician-scientists published the findings today in Open Forum Infectious Diseases, a journal of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. The study involved bamlanivimab, a monoclonal antibody that is now offered only in combination ...

Cultural diversity -- indicated by linguistic diversity -- and biodiversity are linked, and their connection may be another way to preserve both natural environments and Indigenous populations in Africa and perhaps worldwide, according to an international team of researchers.

"The punchline is, that if you are interested in conserving biological diversity, excluding the Indigenous people who likely helped create that diversity in the first place may be a really bad idea," said Larry Gorenflo, professor of landscape architecture, geography and African studies, Penn State. "Humans are part of ecosystems and I hope this study will usher in a more committed effort to engage Indigenous people in conserving localities containing key biodiversity."

Gorenflo, ...

Indigenous people have lived in the Bears Ears region of southeastern Utah for millennia. Ancestral Pueblos built elaborate houses, check dams, agricultural terraces and other modifications of the landscape, leaving ecological legacies that persist to this day. Identifying how humans interacted with past environments is critical for informing how best to protect archaeological sites and ecological diversity in the present. This "archaeo-ecosystem" approach would facilitate co-management of public lands in ways that promote Indigenous health, cultural reclamation and sovereignty.

For the first time, a new study evaluated ecological legacies, archaeo-ecosystem restoration and Indigenous ...

There are roughly 50 billion individual birds in the world, a new big data study by UNSW Sydney suggests - about six birds for every human on the planet.

The study - which bases its findings on citizen science observations and detailed algorithms - estimates how many birds belong to 9700 different bird species, including flightless birds like emus and penguins.

It found many iconic Australian birds are numbered in the millions, like the Rainbow Lorikeet (19 million), Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (10 million) and Laughing Kookaburra (3.4 million). But other natives, like the rare Black-breasted Buttonquail, only have around 100 members left.

The findings are being published this week in the Proceedings ...

Scientists studying the impact of record heat and drought on intact African tropical rainforests were surprised by how resilient they were to the extreme conditions during the last major El Niño event.

The international study, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences today, found that intact rainforests across tropical Africa continued to remove carbon from the atmosphere before and during the 2015-2016 El Niño, despite the extreme heat and drought.

Tracking trees in 100 different tropical rainforests across six African countries, the researchers found that intact forests across the continent still removed 1.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year from the atmosphere during the El Niño monitoring ...

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have followed the progression of breast cancer in an animal model and discovered a path that transforms a slow-growing type of cancer known as estrogen receptor (ER)+/HER2+ into a fast-growing ER-/HER2+ type that aggressively spreads or metastasizes to other organs.

The study, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has implications for breast cancer therapy as it suggests the need to differentiate cancer subtypes according to the path the cells follow. Different paths might be linked to different cancer behavior, which should be taken into consideration to plan treatment appropriately.

"In ...

Scientists have detected new early-warning signals indicating that the central-western part of the Greenland Ice Sheet may undergo a critical transition relatively soon. Because of rising temperatures, a new study by researchers from Germany and Norway shows, the destabilization of the ice sheet has begun and the process of melting may escalate already at limited warming levels. A tipping of the ice sheet would substantially increase long-term global sea level rise.

"We have found evidence that the central-western part of the Greenland ice sheet has been destabilizing and is now close to a critical transition," explains lead author Niklas ...

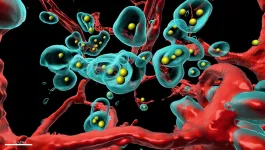

A new technology developed by UZH researchers enables the body to produce therapeutic agents on demand at the exact location where they are needed. The innovation could reduce the side effects of cancer therapy and may hold the solution to better delivery of Covid-related therapies directly to the lungs.

Scientists at the University of Zurich have modified a common respiratory virus, called adenovirus, to act like a Trojan horse to deliver genes for cancer therapeutics directly into tumor cells. Unlike chemotherapy or radiotherapy, this approach does no harm to normal healthy cells. Once inside tumor cells, the delivered genes serve as a blueprint for therapeutic ...

When doctors or scientists want to peer into living tissue, there's always a trade-off between how deep they can probe and how clear a picture they can get.

With light microscopes, researchers can see submicron-resolution structures inside cells or tissue, but only as deep as the millimeter or so that light can penetrate without scattering. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio frequencies that can reach everywhere in the body, but the technique provides low resolution -- about a millimeter, or 1,000 times worse than light.

A University of California, Berkeley, researcher has now shown that microscopic ...

PHILADELPHIA and MELBOURNE, Australia -- (May. 17, 2021) -- A team of scientists from The Wistar Institute in Philadelphia and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center in Melbourne, Australia, discovered a new checkpoint mechanism that fine-tunes gene transcription. As reported in a study published in Cell, a component of the Integrator protein complex tethers the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to the site of transcription allowing it to stop the activity of the RNA polymerase II enzyme (RNAPII). Disruption of this mechanism leads to unrestricted gene transcription and is implicated in cancer.

The study points to new viable opportunities for therapeutic ...