INFORMATION:

Notes to Editors

The 2015-2016 El Niño southern oscillation (ENSO) caused record rainfall, cyclones, droughts and raised temperatures globally.

ENSO is a recurring phenomenon caused by a rise in the temperature of the Pacific Ocean, which impacts the atmosphere and affects the climate around the world. There have been three major ENSO events in the past 50 years, 2015-2016, 1997-1998, and 1982-1983.

Most datasets show 2016 and 2020 as joint record holders for global temperature. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/2020-tied-for-warmest-year-on-record-nasa-analysis-shows

In the paper the carbon sink is reported in units of billion tonnes of carbon, because trees store carbon (1 billion tonnes C = 1 Pg C). To convert carbon sequestered in trees to carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, multiply by 3.667. The overall sink during the El Niño is 0.29 Pg C per year, equivalent to 1.1 billion tonnes carbon dioxide per year.

The forest inventory data part of the African Topical Rainforest Observatory Network, covering 13 countries in Africa, http://www.afritron.org. The data is curated at http://www.forestplots.net.

The research was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and the European Research Council.

Further information

Pictures: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1hBFBkzcVUSosCp8IE9qE2z8zUgZ12cOvTBC

For media enquiries contact University of Leeds press officer Lauren Ballinger on L.ballinger@leeds.ac.uk.

The University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 38,000 students from more than 150 different countries, and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. The University plays a significant role in the Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes.

We are a top ten university for research and impact power in the UK, according to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, and are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings 2021.

The University was awarded a Gold rating by the Government's Teaching Excellence Framework in 2017, recognising its 'consistently outstanding' teaching and learning provision. Twenty-six of our academics have been awarded National Teaching Fellowships - more than any other institution in England, Northern Ireland and Wales - reflecting the excellence of our teaching. http://www.leeds.ac.uk

Follow University of Leeds or tag us in to coverage: Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Instagram

African rainforests still slowed climate change despite record heat and drought

2021-05-17

(Press-News.org) Scientists studying the impact of record heat and drought on intact African tropical rainforests were surprised by how resilient they were to the extreme conditions during the last major El Niño event.

The international study, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences today, found that intact rainforests across tropical Africa continued to remove carbon from the atmosphere before and during the 2015-2016 El Niño, despite the extreme heat and drought.

Tracking trees in 100 different tropical rainforests across six African countries, the researchers found that intact forests across the continent still removed 1.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year from the atmosphere during the El Niño monitoring period. This rate is equivalent to three times the carbon dioxide emissions of the UK in 2019.

During 2015-2016 African rainforests experienced warming of 0.92 degrees Celsius above the 1980-2010 average, and the strongest drought on record, both driven by the El Niño conditions on top of ongoing climate change. This event gave the scientists a unique opportunity to investigate how Africa's vast tropical rainforests could react to heat and drought.

Lead author Dr Amy Bennett, in Leeds' School of Geography, said: "We saw no sharp slowdown of tree growth, nor a big rise in tree deaths, as a result of the extreme climatic conditions. Overall, the uptake of carbon dioxide by these intact rainforests reduced by 36%, but they continued to function as a carbon sink, slowing the rate of climate change."

Tree measurements in long-term inventory plots in intact forest -- unaffected by logging or fire -- were completed just before the 2015-2016 El Niño struck. Emergency re-measurements of 46,000 trees across 100 of the plots in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Ghana, Liberia and the Republic of the Congo then allowed the researchers the first ever opportunity to directly investigate how African tropical forests would react to the hotter, drier conditions.

Senior author Professor Simon Lewis, in Leeds' School of Geography, who led the development of the Africa-wide network of forest observations, said: "Scrambling field-teams to get to our remote rainforest sites was worth all the difficulties we faced. This is the first on-the-ground evidence of what happens when you heat and drought an intact African rainforest. What we found surprised me.

"African rainforests appear more resistant to some additional warming and drought compared to rainforests in Amazonia and Borneo."

African rainforests exist in relatively dry conditions compared to those across much of Amazonia and Southeast Asia. The researchers wanted to establish whether this made them particularly vulnerable to extreme climatic conditions, or if the abundance of drought-adapted tree species occurring in African forests meant that they were less vulnerable to additional warmth and drought.

The results showed that the biggest trees in the forest were largely unaffected, whereas the smaller trees grew less and died more during El Niño, potentially due to having less access to water than the larger trees.

Yet these negative effects had only modest impacts. African rainforests continued to function as a carbon sink, as the changes in the smaller trees were too small to stop the long-term increase in overall tree biomass seen in these forests over the last three decades.

Professor Lewis said: "These findings show the value of careful long-term monitoring of tropical forests. The baseline data running back to the 1980s allowed us to evaluate how well these rainforests coped with record heat and drought."

Past evidence from similar inventory networks in Amazonia studying major droughts in 2005 and 2010, and in Asia studying the large 1997-1998 El Niño event, show either substantially slower tree growth or much greater tree mortality in response to extreme drought and heat. In all these cases, the conditions led to a temporary halting or reversal of the tropical forest carbon sink in these regions.

Co-author Professor Bonaventure Sonké, from University of Yaoundé I (CORRECT) in Cameroon said, "Our results highlight just how important it is to protect African rainforests - they are providing valuable services to us all. The resistance of intact African tropical forests to a bit more heat and drought than they have experienced in the past is welcome news. But we still need to cut carbon dioxide emissions fast, as our forests will probably only resist limited further rises in air temperature."

Dr Bennett added: "African tropical forests play an important role in the global carbon cycle, absorbing 1.7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year in the 2000s. To discover that they will be able to tolerate the predicted conditions of the near future is an unusual source of optimism in climate change science.

"Our results provide a further incentive to keep global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as outlined in the Paris Agreement, as these forests look to be able to withstand limited increases in temperature and drought."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A path to aggressive breast cancer

2021-05-17

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have followed the progression of breast cancer in an animal model and discovered a path that transforms a slow-growing type of cancer known as estrogen receptor (ER)+/HER2+ into a fast-growing ER-/HER2+ type that aggressively spreads or metastasizes to other organs.

The study, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has implications for breast cancer therapy as it suggests the need to differentiate cancer subtypes according to the path the cells follow. Different paths might be linked to different cancer behavior, which should be taken into consideration to plan treatment appropriately.

"In ...

Parts of Greenland may be on the verge of tipping: New early-warning signals detected

2021-05-17

Scientists have detected new early-warning signals indicating that the central-western part of the Greenland Ice Sheet may undergo a critical transition relatively soon. Because of rising temperatures, a new study by researchers from Germany and Norway shows, the destabilization of the ice sheet has begun and the process of melting may escalate already at limited warming levels. A tipping of the ice sheet would substantially increase long-term global sea level rise.

"We have found evidence that the central-western part of the Greenland ice sheet has been destabilizing and is now close to a critical transition," explains lead author Niklas ...

New technology makes tumor eliminate itself

2021-05-17

A new technology developed by UZH researchers enables the body to produce therapeutic agents on demand at the exact location where they are needed. The innovation could reduce the side effects of cancer therapy and may hold the solution to better delivery of Covid-related therapies directly to the lungs.

Scientists at the University of Zurich have modified a common respiratory virus, called adenovirus, to act like a Trojan horse to deliver genes for cancer therapeutics directly into tumor cells. Unlike chemotherapy or radiotherapy, this approach does no harm to normal healthy cells. Once inside tumor cells, the delivered genes serve as a blueprint for therapeutic ...

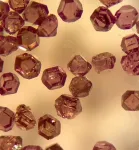

Diamonds engage both optical microscopy and MRI for better imaging

2021-05-17

When doctors or scientists want to peer into living tissue, there's always a trade-off between how deep they can probe and how clear a picture they can get.

With light microscopes, researchers can see submicron-resolution structures inside cells or tissue, but only as deep as the millimeter or so that light can penetrate without scattering. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio frequencies that can reach everywhere in the body, but the technique provides low resolution -- about a millimeter, or 1,000 times worse than light.

A University of California, Berkeley, researcher has now shown that microscopic ...

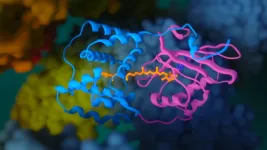

Fundamental mechanism discovered that fine-tunes gene expression & is disrupted in cancer

2021-05-17

PHILADELPHIA and MELBOURNE, Australia -- (May. 17, 2021) -- A team of scientists from The Wistar Institute in Philadelphia and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center in Melbourne, Australia, discovered a new checkpoint mechanism that fine-tunes gene transcription. As reported in a study published in Cell, a component of the Integrator protein complex tethers the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to the site of transcription allowing it to stop the activity of the RNA polymerase II enzyme (RNAPII). Disruption of this mechanism leads to unrestricted gene transcription and is implicated in cancer.

The study points to new viable opportunities for therapeutic ...

Scientists shed light on the mechanism of photoactivation of the orange carotenoid protein

2021-05-17

Exposure to light is compulsory for photosynthetic organisms for the conversion of inorganic compounds into organic ones. However, if there is too much solar energy, the photosystems and other cell components could be damaged. Thanks to special protective proteins, the overexcitation is converted into heat - in the process called non-photochemical quenching. The object of the published study, OCP, was one of such defenders. It was first isolated in 1981 from representatives of the ancient group of photosynthetic bacteria, ?yanobacteria. OCP comprises two domains forming a cavity, in which a carotenoid pigment is embedded.

"When light is absorbed by the carotenoid molecule, OCP can change from an inactive orange to an active red form. ...

Study reveals new options to help firms improve the food recall process

2021-05-17

For much of the nation's food supply, removing unsafe products off of store shelves can take up to 10 months, according to news reports -- even when people are getting sick.

The growing complexity and scope of modern supply chains result in painfully slow product recalls, even when consumer well-being is at stake. For example, in 2009, salmonella-tainted peanuts killed nine people and sickened more than 700 in 46 states, and the resulting nationwide recall cost peanut farmers, their wholesale customers and retailers more than $1 billion in lost production ...

Therapeutics that can shut down harmful genes need a reliable delivery system

2021-05-17

Viruses attack the body by sending their genetic code -- DNA and RNA -- into cells and multiplying. A promising class of therapeutics that uses synthetic nucleic acids to target and shut down specific, harmful genes and prevent viruses from spreading is gaining steam.

However, only a handful of siRNA, or other RNA interference-based therapeutics have been approved. One of the main problems is getting the siRNA into the body and guiding it to the target.

Chemical engineering researchers in the Cockrell School of Engineering aim to solve that problem, while improving the targeting effectiveness of siRNA. In a new paper in the Journal of Controlled Release, the researchers created several different types of nanoparticles and analyzed them for the ability to deliver and protect siRNA from ...

Civil commitment for substance use disorder treatment -- what do addiction medicine specialists think?

2021-05-17

May 17, 2021 - Amid the rising toll of opioid overdoses and deaths in the U.S., several states are considering laws enabling civil commitment for involuntary treatment of patients with substance use disorders (SUDs). Most addiction medicine physicians support civil commitment for SUD treatment - but others strongly oppose this approach, reports a survey study in Journal of Addiction Medicine, the official journal of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Civil commitment has emerged as a sometimes compelling yet controversial policy option," according to the new study, led by Abhishek Jain, MD. At the time of ...

Alcohol problems severely undertreated

2021-05-17

Some 16 million Americans are believed to have alcohol use disorder, and an estimated 93,000 people in the U.S. die from alcohol-related causes each year. Both of those numbers are expected to grow as a result of heavier drinking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet, in a new study involving data from more than 200,000 people with and without alcohol problems, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found that although the vast majority of those with alcohol use disorder see their doctors regularly for a range of issues, fewer than one in 10 ever get treatment for drinking.

The findings are published in the June issue of the journal Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research.

Analyzing data gathered from 2015 through 2019 via the National ...