(Press-News.org) Scientists have long thought that there was a direct connection between the rise in atmospheric oxygen, which started with the Great Oxygenation Event 2.5 billion years ago, and the rise of large, complex multicellular organisms.

That theory, the "Oxygen Control Hypothesis," suggests that the size of these early multicellular organisms was limited by the depth to which oxygen could diffuse into their bodies. The hypothesis makes a simple prediction that has been highly influential within both evolutionary biology and geosciences: Greater atmospheric oxygen should always increase the size to which multicellular organisms can grow.

It's a hypothesis that's proven difficult to test in a lab. Yet a team of Georgia Tech researchers found a way -- using directed evolution, synthetic biology, and mathematical modeling -- all brought to bear on a simple multicellular lifeform called a 'snowflake yeast'. The results? Significant new information on the correlations between oxygenation of the early Earth and the rise of large multicellular organisms -- and it's all about exactly how much O2 was available to some of our earliest multicellular ancestors.

"The positive effect of oxygen on the evolution of multicellularity is entirely dose-dependent -- our planet's first oxygenation would have strongly constrained, not promoted, the evolution of multicellular life," explains G. Ozan Bozdag, research scientist in the School of Biological Sciences and the study's lead author. "The positive effect of oxygen on multicellular size may only be realized when it reaches high levels."

"Oxygen suppression of macroscopic multicellularity" is published in the May 14, 2021 edition of the journal Nature Communications. Bozdag's co-authors on the paper include Georgia Tech researchers Will Ratcliff, associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences; Chris Reinhard, associate professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences; Rozenn Pineau, Ph.D. student in the School of Biological Sciences and the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Quantitative Biosciences (QBioS); along with Eric Libby, assistant professor at Umea University in Sweden and the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico.

Directing yeast to evolve in record time

"We show that the effect of oxygen is more complex than previously imagined. The early rise in global oxygen should in fact strongly constrain the evolution of macroscopic multicellularity, rather than selecting for larger and more complex organisms," notes Ratcliff.

"People have long believed that the oxygenation of Earth's surface was helpful -- some going so far as to say it is a precondition -- for the evolution of large, complex multicellular organisms," he adds. "But nobody has ever tested this directly, because we haven't had a model system that is both able to undergo lots of generations of evolution quickly, and able to grow over the full range of oxygen conditions," from anaerobic conditions up to modern levels.

The researchers were able to do that, however, with snowflake yeast, simple multicellular organisms capable of rapid evolutionary change. By varying their growth environment, they evolved snowflake yeast for over 800 generations in the lab with selection for larger size.

The results surprised Bozdag. "I was astonished to see that multicellular yeast doubled their size very rapidly when they could not use oxygen, while populations that evolved in the moderately oxygenated environment showed no size increase at all," he says. "This effect is robust -- even over much longer timescales."

Size -- and oxygen levels -- matter for multicellular growth

In the team's research, "large size easily evolved either when our yeast had no oxygen or plenty of it, but not when oxygen was present at low levels," Ratcliff says. "We did a lot more work to show that this is actually a totally predictable and understandable outcome of the fact that oxygen, when limiting, acts as a resource -- if cells can access it, they get a big metabolic benefit. When oxygen is scarce, it can't diffuse very far into organisms, so there is an evolutionary incentive for multicellular organisms to be small -- allowing most of their cells access to oxygen -- a constraint that is not there when oxygen simply isn't present, or when there's enough of it around to diffuse more deeply into tissues."

Ratcliff says not only does his group's work challenge the Oxygen Control Hypothesis, it also helps science understand why so little apparent evolutionary innovation was happening in the world of multicellular organisms in the billion years after the Great Oxygenation Event. Ratcliff explains that geologists call this period the "Boring Billion" in Earth's history -- also known as the Dullest Time in Earth's History, and Earth's Middle Ages -- a period when oxygen was present in the atmosphere, but at low levels, and multicellular organisms stayed relatively small and simple.

Bozdag adds another insight into the unique nature of the study. "Previous work examined the interplay between oxygen and multicellular size mainly through the physical principles of gas diffusion," he says. "While that reasoning is essential, we also need an inclusive consideration of principles of Darwinian evolution when studying the origin of complex multicellular life on our planet." Finally being able to advance organisms through many generations of evolution helped the researchers accomplish just that, Bozdag adds.

INFORMATION:

Citation: Bozdag, G.O., Libby, E., Pineau, R. et al., "Oxygen suppression of macroscopic multicellularity." (Nat Commun 12, 2838 2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23104-0

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant no. DEB-1845363 to W.C.R, NSF grant no. IOS-1656549 to W.C.R., NSF grant no. IOS-1656849 to E.L., and a Packard Foundation Fellowship for Science and Engineering to W.C.R. C.T.R. and W.C.R. acknowledge funding from the NASA Astrobiology Institute.

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a top 10 public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition. The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 40,000 students, representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning. As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

When a person views a familiar image, even having seen it just once before for a few seconds, something unique happens in the human brain.

Until recently, neuroscientists believed that vigorous activity in a visual part of the brain called the inferotemporal (IT) cortex meant the person was looking at something novel, like the face of a stranger or a never-before-seen painting. Less IT cortex activity, on the other hand, indicated familiarity.

But something about that theory, called repetition suppression, didn't hold up for University of Pennsylvania neuroscientist Nicole Rust. "Different images produce different amounts of activation even when they are all novel," says ...

The combination of a carb-heavy diet and poor oral hygiene can leave children with early childhood caries (ECC), a severe form of dental decay that can have a lasting impact on their oral and overall health.

A few years ago, scientists from Penn's School of Dental Medicine found that the dental plaque that gives rise to ECC is composed of both a bacterial species, Streptococcus mutans, and a fungus, Candida albicans. The two form a sticky symbiosis, known scientifically as a biofilm, that becomes extremely virulent and difficult to displace from the tooth surface.

Now, a new study from the group offers a strategy for disrupting this biofilm by targeting the yeast-bacterial interactions ...

In studying COVID-19 testing and positivity rates in West Virginia between March and September 2020, West Virginia University researchers found disparities among Black residents and residents experiencing food insecurity.

Specifically, the researchers found communities with a higher Black population had testing rates six times lower than the state average, which they argue could potentially obscure prevalence estimates. They also found that areas associated with food insecurity had higher levels of testing and a higher rate of positivity.

"This could mean that public health officials are targeting predominately rural areas to keep tabs on how the pandemic will unfold in isolated communities within higher food insecurity," said Brian Hendricks, a research assistant professor with ...

Australian scientists have compared an ancient Greek technique of memorising data to an even older technique from Aboriginal culture, using students in a rural medical school.

The study found that students using a technique called memory palace in which students memorised facts by placinthem into a memory blueprint of the childhood home, allowing them to revisit certain rooms to recapture that data. Another group of students were taught a technique developed by Australian Aboriginal people over more than 50,000 years of living in a custodial relationship with the Australian land.

The ...

Researchers at Michigan Medicine found that people with venom allergies are much more likely to suffer mastocytosis, a bone marrow disorder that causes higher risk of fatal reactions.

The team of allergists examined approximately 27 million United States patients through an insurance database - easily becoming the nation's largest study of allergies to bee and wasp stings, or hymenoptera venom. The results, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, revealed mastocytosis in fewer than 0.1% of venom allergy patients - still near 10 times higher than those without allergies.

"Even though there is mounting interest, mast cell diseases are quite understudied; ...

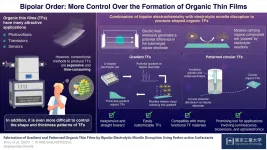

Modern and emerging applications in various fields have found creative uses for organic thin films (TFs); some prominent examples include sensors, photovoltaic systems, transistors, and optoelectronics. However, the methods currently available for producing TFs, such as chemical vapor deposition, are expensive and time-consuming, and often require highly controlled conditions. As one would expect, making TFs with specific shapes or thickness distributions is even more challenging. Because unlocking this customizability could spur advances in many sophisticated applications, researchers are actively exploring new approaches for ...

In quiet moments, the brain likes to wander—to the events of tomorrow, an unpaid bill, an upcoming vacation.

Despite little external stimulation in these instances, a part of the brain called the default mode network (DMN) is hard at work. "These regions seem to be active when people aren't asked to do anything in particular, as opposed to being asked to do something cognitively," says Penn neuroscientist Joseph Kable.

Though the field has long suspected that this neural network plays a role in imagining the future, precisely how it works hadn't been fully understood. Now, research from Kable and two former graduate students in his lab, Trishala Parthasarathi, associate director of scientific services at OrtleyBio, and Sangil Lee, a postdoc at University of California, ...

SAN DIEGO (May TK, 2021) - Compared to most other bear species, very little is known about how female Andean bears choose where they give birth to cubs. As a critical component of the reproductive cycle, birthing dens are essential to the survival of South America's only bear species, listed as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

A new study led by Russ Van Horn, Ph.D., published April in the journal Ursus, takes the most detailed look yet at the dens of this species. Van Horn, a population sustainability scientist, leads San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance's Andean bear conservation program. He was joined by colleagues from the University of British Columbia's Department of Forest ...

A large survey of women in California shows significant racial and ethnic differences in the types of personal care products women use on a daily basis. Because many personal care products contain endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) like parabens and phthalates that interfere with the body's hormones, the findings could shed light on how different products influence women's exposures to harmful chemicals that contribute to health inequities.

The study appears in the Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology as part of a special issue focused on health equity. ...

In the midst of a devastating global pandemic of wildlife origin and with future spillovers imminent as humans continue to come into closer contact with wildlife, infectious-disease models that consider the full ecological and anthropological contexts of disease transmission are critical to the health of all life. Existing models are limited in their ability to predict disease emergence, since they rarely consider the dynamics of the hosts and ecosystems from which pandemics emerge.

Published May 17 in Nature Ecology and Evolution, Smithsonian scientists and partners provide a framework for a new approach to modeling infectious diseases. It adapts established methods developed to study the planet's natural systems, including ...