(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - A newly identified group of antibodies that binds to a coating of sugars on the outer shell of HIV is effective in neutralizing the virus and points to a novel vaccine approach that could also potentially be used against SARS-CoV-2 and fungal pathogens, researchers at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute report.

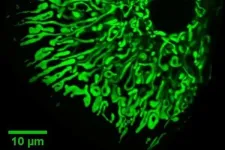

In a study appearing online May 20 in the journal Cell, the researchers describe an immune cell found in both monkeys and humans that produces a unique type of anti-glycan antibody. This newly described antibody has the ability to attach to the outer layer of HIV at a patch of glycans -- the chain-like structures of sugars that are on the surfaces of cells, including the outer shells of viruses.

"This represents a new form of host defense," said senior author Barton Haynes, M.D., director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute (DHVI). "These new antibodies have a special shape and could be effective against a variety of pathogens. It's very exciting."

Haynes and colleagues -- including lead author Wilton Williams, Ph.D., director of the Viral Genetics Analysis Core at DHVI and co-author Priyamvada Acharya, Ph.D., director of the Division of Structural Biology at DHVI -- found the antibody during a series of studies exploring whether there might be an immune response targeted to glycans that cover the outer surface of HIV.

More than 50% of the virus's outer layer is comprised of glycans. Haynes said it has long been a tempting approach to unleash anti-glycan antibodies to break down these sugar structures, triggering immune B-cell lymphocytes to produce antibodies to neutralize HIV.

"Of course, it's not that simple," Haynes said.

Instead, HIV is cloaked in sugars that look like the host's glycans, creating a shield that makes the virus appear to be part of the host rather than a deadly pathogen.

But the newly identified group of anti-glycan antibodies -- referred by the Duke team as Fab-dimerized glycan-reactive (FDG) antibodies -- had gone undiscovered as a potential option.

To date, there was only one report of a similar anti-glycan HIV antibody with an unusual structure that was found 24 years ago (termed 2G12). The Duke team has now isolated several FDG antibodies and found that they display a rare, never-before-seen structure that resembled 2G12. This structure enables the antibody to lock tightly onto a specific, dense patch of sugars on HIV, but not on other cellular surfaces swathed in host glycans.

"The structural and functional characteristics of these antibodies can be used to design vaccines that target this glycan patch on HIV, eliciting a B-cell response that neutralizes the virus," Williams said.

"These antibodies are actually much more common in blood cells than other neutralizing antibodies that target specific regions of the HIV outer layer," Williams said. "That's an exciting finding, because it overcomes one of the biggest complexities associated with other types of broadly neutralizing antibodies."

Williams said the FDG antibodies also bind to a pathogenic yeast called Candida albicans, and to viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19. Additional studies will explore ways of harnessing the antibody and deploying it against these pathogens.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Haynes, Williams and Acharya, study authors include R. Ryan Meyerhoff, R.J. Edwards, Hui Li, Kartik Manne, Nathan I. Nicely, Rory Henderson, Ye Zhou, Katarzyna Janowska, Katayoun Mansouri, Sophie Gobeil, Tyler Evangelous, Bhavna Hora, Madison Berry, A. Yousef Abuahmad, Jordan Sprenz, Margaret Deyton, Victoria Stalls, Megan Kopp, Allen L. Hsu, Mario J. Borgnia, Guillaume Stewart-Jones, Matthew S. Lee, Naomi Bronkema, M. Anthony Moody, Kevin Wiehe, Todd Bradley, S. Munir Alam, Robert J. Parks, Andrew Foulger, Thomas Oguin, Gregory D. Sempowski, Mattia Bonsignori, Celia C. LaBranche, David C. Montefiori, Michael Seaman, Sampa Santra, John Perfect, Joseph R. Francica, Geoffrey M. Lynn, Baptiste Aussedat, William E. Walkowicz, Richard Laga, Garnett Kelsoe, Kevin O. Saunders, Daniela Fera, Peter D. Kwong, Robert A. Seder, Alberto Bartesaghi and George M. Shaw.

The study received funding support from the Consortia for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Development, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS (UM1-AI44371).

Juvenile salmon migrating to the sea in the Sacramento River face a gauntlet of hazards in an environment drastically modified by humans, especially with respect to historical patterns of stream flow. Many studies have shown that survival rates of juvenile salmon improve as the amount of water flowing downstream increases, but "more is better" is not a useful guideline for agencies managing competing demands for the available water.

Now fisheries scientists have identified key thresholds in the relationship between stream flow and salmon survival that can serve as actionable targets for managing water resources in the Sacramento River. The new analysis, published May 19 in Ecosphere, revealed nonlinear ...

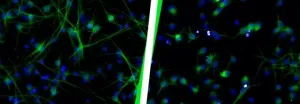

Today, proteins that can be controlled with light are a widely used tool in research to specifically switch certain functions on and off in living organisms. Channelrhodopsins are often used for the technique known as optogenetics: When exposed to light, these proteins open a pore in the cell membrane through which ions can flow in; this is how nerve cells can be activated. A team from the Centre for Protein Diagnostics (PRODI) at Ruhr-Universität Bochum has now used spectroscopy to discover a universal functional mechanism of channelrhodopsins that determines their efficiency as a channel and thus as an optogenetic tool. The researchers led by Professor Klaus ...

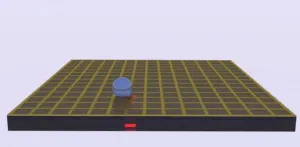

Microfluidic technologies have seen great advances over the past few decades in addressing applications such as biochemical analysis, pharmaceutical development, and point-of-care diagnostics. Miniaturization of biochemical operations performed on lab-on-a-chip microfluidic platforms benefit from reduced sample, reagent, and waste volumes, as well as increased parallelization and automation. This allows for more cost-effective operations along with higher throughput and sensitivity for faster and more efficient sample analysis and detection.

Optoelectrowetting (OEW) is a digital optofluidic technology that is based on the principles of light-controlled electrowetting and enables ...

Since our ancestors infected themselves with retroviruses millions of years ago, we have carried elements of these viruses in our genes - known as human endogenous retroviruses, or HERVs for short. These viral elements have lost their ability to replicate and infect during evolution, but are an integral part of our genetic makeup. In fact, humans possess five times more HERVs in non-coding parts than coding genes. So far, strong focus has been devoted to the correlation of HERVs and the onset or progression of diseases. This is why HERV expression has been studied in samples of pathological origin. Although important, these studies ...

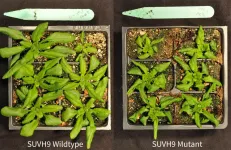

Passing down a healthy genome is a critical part of creating viable offspring. But what happens when you have harmful modifications in your genome that you don't want to pass down? Baby plants have evolved a method to wipe the slate clean and reinstall only the modifications that they need to grow and develop. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor & HHMI Investigator Rob Martienssen and his collaborators, Jean-Sébastien Parent and Institut de Recherche pour le Développement Université de Montpellier scientist Daniel Grimanelli, discovered one of the genes responsible for reinstalling modifications in a baby plant's genome.

A plant's genomic modifications--called epigenetic ...

The study sought to describe and explain gender pay differences in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services between 2010 and 2018. HHS comprises a quarter of the country's governmental public health workers, with over 80,000 employees.

Understanding what may be driving wage gaps at HHS provides opportunities for employers and legislators to take action to support women in the health care field, said lead author Zhuo "Adam" Chen, an associate professor of health policy and management at UGA's College of Public Health.

"A large percentage of the health care workforce are women," said Chen. "If you have underpaid women in the profession, I don't think it spells good things for the public health system."

Chen ...

Maywood, Ill. - May 19, 2021 - A team of scientists from Loyola University Chicago's Stritch School of Medicine have discovered a critical component for renewing the heart's molecular motor, which breaks down in heart failure.

Approximately 6.2 million Americans have heart failure, an often fatal condition characterized by the heart's inability to pump enough blood and oxygen throughout the body. This discovery could represent a novel approach to repair the heart.

Their findings, published in the May 19 issue of Nature Communications, show how a protein called BAG3 helps replace "worn-out" components of the cardiac sarcomere. The sarcomere is a microscopic ...

FINDINGS

A new multi-institution study led by a team of researchers at the David Geffen School of Medicine demonstrated that blocking a protein called ABCB10 in liver cells protects against high blood sugar and fatty liver disease in obese mice. Furthermore, ABCB10 activity prompted insulin resistance in human liver cells.

The findings are the first to show that ABCB10 transports biliverdin out of the mitochondria - the cell's "energy generating powerhouses." Biliverdin is the precursor of bilirubin, a substance with antioxidant properties. Consequently, ABCB10 transport ...

So, you thought the problem of false information on social media could not be any worse? Allow us to respectfully offer evidence to the contrary.

Not only is misinformation increasing online, but attempting to correct it politely on Twitter can have negative consequences, leading to even less-accurate tweets and more toxicity from the people being corrected, according to a new study co-authored by a group of MIT scholars.

The study was centered around a Twitter field experiment in which a research team offered polite corrections, complete with ...

Orangutans are closely related to humans. And yet, they are much less sociable than other species of great apes. Previous studies have showed that young orangutans mainly acquire their knowledge and skills from their mothers and other conspecifics. Social learning in orangutans occurs through peering, i.e. sustained observation of other members of the species at close range.

An international team led by the University of Zurich (UZH) has now studied peering behavior in young orangutans at two research stations on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. The data was collected by researchers from the Department of Anthropology of UZH, the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Constance, the Universitas Nasional in Jakarta and Leipzig University, ...