(Press-News.org) Montréal, May 20, 2021--Researchers at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM) and Yale University have succeeded in reducing the size of the HIV reservoir in humanized mice by using a "molecular can opener" and a combination of antibodies found in the blood of infected individuals.

In their study published in Cell Host & Microbe, the team of scientists, in collaboration with their colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Medical School, show that they were also able to significantly delay the return of the virus after stopping antiretroviral therapy in this animal model.

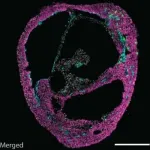

Humanized mice are generated from immunodeficient mice that don't have their own immune system. They are transplanted with human immune cells and can be used to study diseases affecting the human immune system such as cancer, leukemia or HIV. Researchers at Yale University developed a specific humanized mouse model with active Natural Killer cells (NK), a type of immune cell, to study their role in HIV infection.

"With our cocktail of two antibodies naturally present in the plasma of HIV-infected people and a small 'can opener' molecule, we managed to 'open up' and stabilize a vulnerable form of the virus envelope," said the study's co-lead author Andrés Finzi, a researcher at the CRCHUM and professor at Université de Montréal. "The antibodies recognized the virus, had time to call the immune system's 'police', the NK cells, and to get rid of the infected cells."

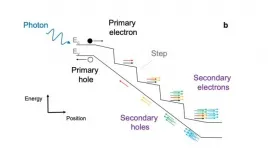

To infect cells of the human immune system, HIV binds with its envelope to specific receptors on the surface of these cells, including one called CD4. This binding triggers changes in the shape of the virus envelope, its "key" to entry, and allows it to infect host cells.

In 2019, in an earlier study, a team led by Finzi and James Munro of Tufts University showed that small CD4-like molecules, designed and synthesized by the Amos Smith Group at the University of Pennsylvania, acted as "can openers" and were able to force the virus to open and expose vulnerable parts of its envelope.

"In our humanized mouse model developed at Yale and used to study HIV, we show that the cocktail not only limits viral replication, it also decreases the HIV reservoir by destroying infected cells," said Priti Kumar, lead author and professor at Yale University.

Successfully delaying the virus's "rebound"

Throughout the course of antiretroviral therapy, HIV hides silently in reservoirs located in CD4+ T lymphocytes, the white blood cells that help activate the immune system against infections and fight microbes.

The existence of these hidden viral sanctuaries explains why antiretroviral therapy does not cure people with HIV and why they must remain on treatment for life to prevent the virus from "rebounding".

"In humanized mice, we stopped antiretroviral therapy before administering our cocktail," said Finzi. "The rebound of the virus occurred 46 days later as opposed to mice that did not get the cocktail, where rebound occurred within 10 days. Such efficiency in this animal model is really very promising."

These findings open up new therapeutic avenues in the fight against this deadly virus. According to the World Health Organization, 38million people were living with HIV at the end of 2019.

INFORMATION:

About the study

The article "Modulating HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein conformation to decrease the HIV-1 reservoir", by Jyothi K. Rajashekar, Jonathan Richard and colleagues, was published May 20, 2021 in Cell Host & Microbe.

The work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Gilead Sciences Research Institute HIV Research Program, and the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR Research Consortium on HIV Eradication). Andrés Finzi holds the Canada Research Chair in Retroviral Entry.

About the CRCHUM

The University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM) is one of North America's leading hospital research centres. It strives to improve adult health through a research continuum covering such disciplines as the fundamental sciences, clinical research and public health. Over 1,850 people work at the CRCHUM, including more than 550 researchers and more than 460 graduate students. chumontreal.qc.ca/crchum

@CRCHUM

About Université de Montréal

Deeply rooted in Montreal and dedicated to its international mission, Université de Montréal is one of the top universities in the French-speaking world. Founded in 1878, Université de Montréal today has 13 faculties and schools, and together with its two affiliated schools, HEC Montréal and Polytechnique Montréal, constitutes the largest centre of higher education and research in Québec and one of the major centres in North America. It brings together 2,400 professors and researchers and has more than 67,000 students. umontreal.ca

Media contact - information and interviews

Lucie Dufresne

Communications and Access-to-Information Directorate

Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM)

(+ 1) 514-890-8000, ext. 15380

lucie.dufresne.chum@ssss.gouv.qc.ca

Realizing the potential of self-driving cars hinges on technology that can quickly sense and react to obstacles and other vehicles in real time. Engineers from The University of Texas at Austin and the University of Virginia created a new first-of-its-kind light detecting device that can more accurately amplify weak signals bouncing off of faraway objects than current technology allows, giving autonomous vehicles a fuller picture of what's happening on the road.

The new device is more sensitive than other light detectors in that it also eliminates inconsistency, or noise, associated with the detection process. Such noise can cause systems to miss signals and put autonomous vehicle passengers at risk.

"Autonomous ...

Scientists from Queen Mary University of London and Rothamsted Research have used radar technology to track male honeybees, called drones, and reveal the secrets of their mating behaviours.

The study suggests that male bees swarm together in specific aerial locations to find and attempt to mate with queens. The researchers found that drones also move between different congregation areas during a single flight.

Drones have one main purpose in life, to mate with queens in mid-air. Beekeepers and some scientists have long believed that drones gather in huge numbers of up to 10,000 in locations known as 'drone congregation areas'. Previous research has used pheromone lures to attract drones, raising concerns ...

What The Study Did: These preliminary findings using U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System data in the early phase of societal COVID-19 vaccination using two messenger RNA vaccines suggest that no association exists between inoculation with a SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine and incident sudden hearing loss.

Authors: Eric J. Formeister, M.D., M.S., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.0869)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed associations between prenatal, early postnatal or current exposure to secondhand smoke and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among school-age children in China.

Authors: Li-Wen Hu, M.D., Ph.D., and Guang-Hui Dong, M.D., Ph.D., of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10931)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

BOSTON - Screening for colorectal cancer - the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States - can save lives by detecting both pre-cancerous lesions that can be removed during the screening procedure, and colorectal cancer in its early stages, when it is highly curable.

Screening is most commonly performed with endoscopy: visualization of the entire colon and rectum using a long flexible optical tube (colonoscopy), or of the lower part of the colon and rectum with a shorter flexible tube (sigmoidoscopy).

This week, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended beginning age for screening from 50 to 45 for persons without a family history of colorectal ...

The discovery of a new species of ancient turtle is shedding light on hard-to-track reptile migrations about 100 million years ago. Pleurochayah appalachius, a bothremydid turtle adapted for coastal life, is described in a new paper published by a multi-institution research group in the journal Scientific Reports.

P. appalachius was discovered at the Arlington Archosaur Site (AAS) of Texas, which preserves the remnants of an ancient Late Cretaceous river delta that once existed in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and is also known for discoveries of fossil crocodyliformes and dinosaurs. P. appalachius belonged to an extinct lineage of pleurodiran (side-necked) ...

For many engineers and scientists, nature is the world's greatest muse. They seek to better understand natural processes that have evolved over millions of years, mimic them in ways that can benefit society and sometimes even improve on them.

An international, interdisciplinary team of researchers that includes engineers from The University of Austin has found a way to replicate a natural process that moves water between cells, with a goal of improving how we filter out salt and other elements and molecules to create clean water while consuming less energy.

In a new paper published today in Nature Nanotechnology, researchers created a molecule-sized water transport channel that can carry water between cells while excluding protons ...

Self-organizing heart organoids developed at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences - are also effective injury- and in vitro congenital disease models. These "cardioids" may revolutionize research into cardiovascular disorders and malformations of the heart. The results are published in the journal Cell.

About 18 million people die each year from cardiovascular diseases, making them the leading cause of fatalities globally. Moreover, the most prevalent birth defects in children pertain to the heart. Currently, a major bottleneck in understanding human heart malformations and developing regenerative therapies are missing human physiological models of the heart.

The research group of Sasha Mendjan established cardioids ...

NEW YORK, NY (May 20, 2021)--The immune nature of kidney cancer stands out when compared to other cancers: More immune cells infiltrate kidney cancers than most other solid tumors, and kidney cancer is one of the most responsive malignancies to today's immunotherapy regimens.

But despite treatment, many patients with clear cell renal carcinoma--the most common type of kidney cancer--eventually relapse and develop incurable metastatic disease.

A new study shows that the presence of a rare and previously unknown type of immune cell in kidney tumors can predict which patients are likely to have cancer recur after surgery. These cells could even ...

We observe water vapor condensing into liquid droplets on a daily basis, be it as dew drops on leaves or as droplets on the lid of a cooking pot. Since the work of Dutch physicist J.D. van der Waals in the 19th century, condensation has been understood to result from attractive forces between the molecules of a fluid.

Now, an international team of researchers has discovered a new mechanism of condensation: Even if they don't attract each other, self-propelled particles can condense by turning toward dense regions, where they accumulate. The study was published in Nature Physics.

"It's like if cars steered toward crowded areas and made the crowd even bigger," explained Steve Granick, director of the IBS Center for Soft and Living ...