(Press-News.org) Scientists from Queen Mary University of London and Rothamsted Research have used radar technology to track male honeybees, called drones, and reveal the secrets of their mating behaviours.

The study suggests that male bees swarm together in specific aerial locations to find and attempt to mate with queens. The researchers found that drones also move between different congregation areas during a single flight.

Drones have one main purpose in life, to mate with queens in mid-air. Beekeepers and some scientists have long believed that drones gather in huge numbers of up to 10,000 in locations known as 'drone congregation areas'. Previous research has used pheromone lures to attract drones, raising concerns that these lures could have inadvertently caused these congregations. This new study is the first ever attempt to track the flight paths of individual drones and observe them in the absence of lures.

Similar mating sites, in which large numbers of males gather, have been observed in other animals but this is the first time males have been observed to move between multiple locations, hinting at the discovery of a new type of animal mating system.

The research is published today in the journal iScience and coincides with the UN designated World Bee Day (20 May), which aims to raise awareness of the importance of pollinators, the threats they face and their contribution to sustainable development.

To track the flight paths of drones, researchers attached a small antenna-like electronic device, known as a transponder, to the back of individual honeybees. When the transponder receives a radar signal from the transmitter, it absorbs its energy and converts it into a higher frequency signal, which is then detected by the radar antenna. As the transponders signal is twice the frequency of the initial signal, it is easily identifiable and cannot be confused with reflections of the original signal from objects in the surrounding environment, such as trees of buildings.

Using this system the researchers are able to track the bee's position relative to the radar every 3 seconds with an accuracy of around 2m. The team then used the positions of known landmarks within the outdoor experimental field site to determine the true GPS position of each bee.

The scientists found that drones alternated between periods of straight and convoluted, looping flight patterns within a single flight. On further investigation they showed that phases of looping flight were associated with four distinct aerial locations where drones congregated and these specific areas were consistent over a two year period.

The researchers propose that drone congregation areas could function like 'leks', mating systems in which large numbers of males gather solely in an attempt to mate. Lek systems are most well known in vertebrates, like deer and grouse, and males are typically faithful to a single lek location.

Dr Joe Woodgate, a Postdoctoral Researcher at Queen Mary and lead author of the study, said: "By using harmonic radar technology to track the bees, we found that individual flight paths show a clear change of behaviour from straight flight to looping flight. Periods of looping flight were clustered in particular locations and repeatable over two years, confirming that stable drone congregation areas, similar to 'leks' in other species, do exist."

"We show that drones frequently visited more than one congregation area on a single flight. This is the first evidence for males of any species routinely moving between lek-like congregations and may represent a new form of lek-like mating system in honeybees."

Interestingly, the study highlights similarities between the behaviour of drones within these congregation areas to swarms of midges or mosquitos. The researchers observed that when drones are making looping flight in one of these areas, the further they go from the centre, the harder they accelerate back towards it. This creates an apparent force, drawing bees toward the centre and leading to a stable, coherent swarm despite individual drones only spending a short time at each location.

The researchers still don't understand how the drones find these congregation areas in the first place. Drones are born in Summer and their average lifespan is only around 20 days, so new generations can't find these areas by following older drones. "Our findings suggest drones locate congregation areas as early as their second ever flight, without apparent extensive search. This implies that they must be able to get the information required to guide them to a congregation from observing the landscape close to their hive. In the future, we will look at how they accomplish this feat," said Professor Lars Chittka, Professor of Sensory and Behavioural Ecology at Queen Mary and supervisor of the project.

The work was supported by grants from the European Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Dr Joe Woodgate, the lead researcher for the study is also part of the EPSRC-funded 'Brains on Board' programme that aims to create robots with the navigational abilities of bees. He added: "We believe that bee-inspired robotics will play a role in improving robotics and artificial intelligence in the future. Understanding how bees select and find distant goals based on their explorations of their surroundings will be important for this."

INFORMATION:

Notes to editors

* Research publication: 'Harmonic radar tracking reveals that honeybee drones navigate between multiple aerial leks' Joseph L. Woodgate, James C. Makinson, Natacha Rossi, Ka S. Lim, Andrew M. Reynolds, Christopher J. Rawlings, Lars Chittka, iScience, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102499.

* After the article publishes, it will be available at: https://www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext/S2589-0042(21)00467-3.

* Additional supporting images and videos available on request.

* For a copy of the paper or more information please contact:

Sophie McLachlan

Faculty Communications Manager (Science & Engineering)

Queen Mary University of London

sophie.mclachlan@qmul.ac.uk

Tel: 020 7882 3787

About Queen Mary

Queen Mary University of London is a research-intensive university that connects minds worldwide. A member of the prestigious Russell Group, we work across the humanities and social sciences, medicine and dentistry, and science and engineering, with inspirational teaching directly informed by our world-leading research. In the most recent Research Excellence Framework we were ranked 5th in the country for the proportion of research outputs that were world-leading or internationally excellent. We have over 25,000 students and offer more than 240 degree programmes. Our reputation for excellent teaching was rewarded with silver in the most recent Teaching Excellence Framework. Queen Mary has a proud and distinctive history built on four historic institutions stretching back to 1785 and beyond. Common to each of these institutions - the London Hospital Medical College, St Bartholomew's Medical College, Westfield College and Queen Mary College - was the vision to provide hope and opportunity for the less privileged or otherwise under-represented. Today, Queen Mary University of London remains true to that belief in opening the doors of opportunity for anyone with the potential to succeed and helping to build a future we can all be proud of.

What The Study Did: These preliminary findings using U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System data in the early phase of societal COVID-19 vaccination using two messenger RNA vaccines suggest that no association exists between inoculation with a SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine and incident sudden hearing loss.

Authors: Eric J. Formeister, M.D., M.S., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.0869)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed associations between prenatal, early postnatal or current exposure to secondhand smoke and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among school-age children in China.

Authors: Li-Wen Hu, M.D., Ph.D., and Guang-Hui Dong, M.D., Ph.D., of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10931)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

BOSTON - Screening for colorectal cancer - the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States - can save lives by detecting both pre-cancerous lesions that can be removed during the screening procedure, and colorectal cancer in its early stages, when it is highly curable.

Screening is most commonly performed with endoscopy: visualization of the entire colon and rectum using a long flexible optical tube (colonoscopy), or of the lower part of the colon and rectum with a shorter flexible tube (sigmoidoscopy).

This week, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended beginning age for screening from 50 to 45 for persons without a family history of colorectal ...

The discovery of a new species of ancient turtle is shedding light on hard-to-track reptile migrations about 100 million years ago. Pleurochayah appalachius, a bothremydid turtle adapted for coastal life, is described in a new paper published by a multi-institution research group in the journal Scientific Reports.

P. appalachius was discovered at the Arlington Archosaur Site (AAS) of Texas, which preserves the remnants of an ancient Late Cretaceous river delta that once existed in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and is also known for discoveries of fossil crocodyliformes and dinosaurs. P. appalachius belonged to an extinct lineage of pleurodiran (side-necked) ...

For many engineers and scientists, nature is the world's greatest muse. They seek to better understand natural processes that have evolved over millions of years, mimic them in ways that can benefit society and sometimes even improve on them.

An international, interdisciplinary team of researchers that includes engineers from The University of Austin has found a way to replicate a natural process that moves water between cells, with a goal of improving how we filter out salt and other elements and molecules to create clean water while consuming less energy.

In a new paper published today in Nature Nanotechnology, researchers created a molecule-sized water transport channel that can carry water between cells while excluding protons ...

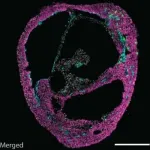

Self-organizing heart organoids developed at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences - are also effective injury- and in vitro congenital disease models. These "cardioids" may revolutionize research into cardiovascular disorders and malformations of the heart. The results are published in the journal Cell.

About 18 million people die each year from cardiovascular diseases, making them the leading cause of fatalities globally. Moreover, the most prevalent birth defects in children pertain to the heart. Currently, a major bottleneck in understanding human heart malformations and developing regenerative therapies are missing human physiological models of the heart.

The research group of Sasha Mendjan established cardioids ...

NEW YORK, NY (May 20, 2021)--The immune nature of kidney cancer stands out when compared to other cancers: More immune cells infiltrate kidney cancers than most other solid tumors, and kidney cancer is one of the most responsive malignancies to today's immunotherapy regimens.

But despite treatment, many patients with clear cell renal carcinoma--the most common type of kidney cancer--eventually relapse and develop incurable metastatic disease.

A new study shows that the presence of a rare and previously unknown type of immune cell in kidney tumors can predict which patients are likely to have cancer recur after surgery. These cells could even ...

We observe water vapor condensing into liquid droplets on a daily basis, be it as dew drops on leaves or as droplets on the lid of a cooking pot. Since the work of Dutch physicist J.D. van der Waals in the 19th century, condensation has been understood to result from attractive forces between the molecules of a fluid.

Now, an international team of researchers has discovered a new mechanism of condensation: Even if they don't attract each other, self-propelled particles can condense by turning toward dense regions, where they accumulate. The study was published in Nature Physics.

"It's like if cars steered toward crowded areas and made the crowd even bigger," explained Steve Granick, director of the IBS Center for Soft and Living ...

Antiretroviral therapy, the common approach in the treatment of HIV, halts replication of the virus and has saved the lives of millions of people. However, for patients the drug cocktail becomes a lifetime necessity because they continue to harbor latent HIV in a small number of immune system cells. In the absence of treatment, HIV can again replicate and rebound into full blown AIDs.

A new study, however, suggests that addition of a single small molecule can rip away the cloak that shields those cells containing HIV and make them susceptible the patient's own antibodies that otherwise are not normally of much use against HIV.

For the study, a team of researchers ...

HOUSTON - Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have developed a first-of-its-kind artificial intelligence (AI)-based tool that can accurately identify rare groups of biologically important cells from single-cell datasets, which often contain gene or protein expression data from thousands of cells. The research was published today in Nature Computational Science.

This computational tool, called SCMER (Single-Cell Manifold presERving feature selection), can help researchers sort through the noise of complex datasets to study cells that would likely not be identifiable otherwise.

SCMER may be used broadly for many applications in oncology and beyond, explained senior author Ken Chen, Ph.D., associate professor of Bioinformatics ...