What makes some oysters more resilient than others?

New research by Louisiana State University biologists offers insight into this commercially important species

2021-05-20

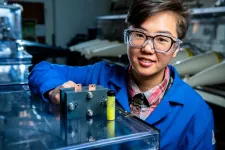

(Press-News.org) Oysters live and grow in saltwater. However, the saltiness of their habitat can change dramatically, especially where the mighty Mississippi River flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Louisiana oysters from the northern Gulf of Mexico may experience some of the lowest salinity in the world due to the influx of fresh water from the Mississippi River. In addition, increased rainfall and large-scale river diversions for coastal protection will bring more fresh water that does not bode well for the eastern oyster. New research led by Louisiana State University (LSU) alumna Joanna Griffiths from Portland, Oregon, and her faculty advisor LSU Department of Biological Sciences Associate Professor Morgan Kelly reveals new information on why some oysters may be more resilient to freshwater than others. Their findings published this week have a significant impact on this commercially important marine species.

"Oysters are known to be tolerant to a wide breadth of salinity. That's generally true of a lot of oysters because they can close up their shell. But as larvae, they don't have that shell structure to protect them," said Griffiths, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at U.C. Davis.

She conducted an extensive study as part of her doctoral dissertation on oyster larvae survival and growth. She investigated whether having parents who have lived in environments with low salinity will produce offspring that are more resistant to low salinity based on a concept called transgenerational plasticity that would suggest one generation's flexibility is passed on to the next generation.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers spawned and raised oysters at the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Michael C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery in Grand Isle in 2016. They transplanted 240 of these oysters into coastal waters at two different locations -- a low salinity site by the Louisiana University Marine Consortium, or LUMCON, in Chauvin, and a medium salinity site by the Louisiana Sea Grant Oyster Research and Demonstration Farm in Grand Isle. After two years, the researchers collected the oysters and found the oysters at the saltier site in Grand Isle were 40 percent larger than the ones from LUMCON thus showing that environment can affect development. Then, the researchers spawned the next generation to see what flexibility characteristics could be passed down from parent to offspring.

Griffiths meticulously cross-bred oysters from both sites and produced 240 oyster families. She and four colleagues tended to the oyster larvae around-the-clock.

"This type of experiment that Joanna did is a lot of work," Kelly said. "It is a lot of record-keeping. You have to be ready at every developmental stage of the baby oysters. A little bit like having a human baby, you have to be up in the middle of the night sometimes getting ready for the next stage of the oyster larvae life cycle. There are a lot of sleepless nights breeding oysters."

Catastrophically, the breeding experiment failed and no oyster larvae survived. Griffiths repeated the experiment and again it failed.

"It was hard to put in a lot of work and get absolutely nothing from it," she said.

But on the third try, she succeeded.

Of the 240 oyster families, about 60 families of larvae survived after five days.

Griffiths measured the larvae and found that the offspring of the parents who had lived at the low salinity site by LUMCON were not more resilient to low salinity. She used size as a measure of success because the larger an oyster larva is, the less time they need to spend in the water column where they are vulnerable to predators before metamorphosizing and settling onto a reef.

She found that some families of oysters do well under low salinity and some families do poorly. The oysters that do well have some variation of a gene that helps them grow well no matter what environment.

"We were surprised how much genetic variation they have and how heritable the resilient trait is," Griffiths said.

These results suggest that selective breeding in hatchery management practices may be an effective way of increasing resiliency for low salinity tolerance in eastern oysters.

"I've experienced a lot of failures during my Ph.D., but I think they have made me a better scientist. I might be studying the resilience of oysters to stress, but it's this project that has made me more resilient as a scientist. I know I can deal with difficult and tough circumstances and I'm now grateful for those failures!"

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-20

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- You might be older - or younger - than you think. A new study found that differences between a person's age in years and his or her biological age, as predicted by an artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled EKG, can provide measurable insights into health and longevity.

The AI model accurately predicted the age of most subjects, with a mean age gap of 0.88 years between EKG age and actual age. However, a number of subjects had a gap that was much larger, either seemingly much older or much younger by EKG age.

The likelihood to die during follow-up was much ...

2021-05-20

During the pandemic, the old waiting room phrase "the doctor will see you now" has taken on a new meaning. So has the waiting room. Our kitchen table or living room couch is where many people do work lately, and that includes visits to the doctor. New research from Syracuse University's Falk College indicates this method of health care will continue even after COVID numbers are (hopefully) reduced.

"I was surprised by the results," said the study's lead author Bhavneet Walia, assistant professor of public health at Syracuse University. "I initially thought that, because of the challenges of telehealth, physicians would not be in favor of continuing post-pandemic. It turns out they do. But ...

2021-05-20

Researchers have long been interested in finding ways to use simple hydrocarbons, chemicals made of a small number of carbon and hydrogen atoms, to create value-added chemicals, ones used in fuels, plastics, and other complex materials. Methane, a major component of natural gas, is one such chemical that scientists would like to find to ways to use more effectively, since there is currently no environmentally friendly and large-scale way to utilize this potent greenhouse gas.

A new paper in Science provides an updated understanding of how to add functional groups onto simple hydrocarbons like methane. Conducted by graduate students Qiaomu Yang and Yusen Qiao, postdoc Yu Heng Wang, and led by professors Patrick J. Walsh and Eric J. Schelter, this new and highly detailed mechanism ...

2021-05-20

HOUSTON - (May 20, 2021) - It's always good when your hard work reflects well on you.

With the discovery of the giant polarization rotation of light, that is literally so.

The ultrathin, highly aligned carbon nanotube films first made by Rice University physicist Junichiro Kono and his students a few years ago turned out to have a surprising phenomenon waiting within: an ability to make highly capable terahertz polarization rotation possible.

This rotation doesn't mean the films are spinning. It does mean that polarized light from a laser or other source can now be manipulated in ways that were previously out of reach, making it completely visible or completely opaque with a device that's extremely ...

2021-05-20

At the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, a University of Illinois Chicago researcher conducted a survey asking respondents if they experienced health care delays because of the pandemic. In addition to learning about the types of delays, the study also presented a unique opportunity to capture a historic moment at the pandemic's beginning.

Elizabeth Papautsky, UIC assistant professor of biomedical and health information sciences, is first author on "Characterizing Healthcare Delays and Interruptions in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Data from an Internet-Based Cross-Sectional ...

2021-05-20

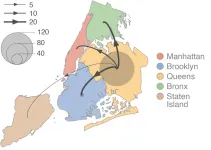

During the first phase of the COVID-19 epidemic, New York City experienced high prevalence compared to other U.S. cities, yet little is known about the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 within and among its boroughs. A study published in PLOS Pathogens by Simon Dellicour at Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium, Ralf Duerr and Adriana Heguy at New York University, USA, and colleagues describe the dispersal dynamics of COVID-19 viral lineages at the state and city levels, illustrating the relatively important role of the borough of Queens as a SARS-CoV-2 transmission hub.

To better understand how the virus dispersed throughout New York ...

2021-05-20

Ancient pollen samples and a new statistical approach may shed light on the global rate of change of vegetation and eventually on how much climate change and humans have played a part in altering landscapes, according to an international team of researchers.

"We know that climate and people interact with natural ecosystems and change them," said Sarah Ivory, assistant professor of geosciences and associate in the Earth and Environmental Systems Institute, Penn State. "Typically, we go to some particular location and study this by teasing apart these influences. In particular, we know that the impact people have goes back much earlier than what is typically ...

2021-05-20

A compound used widely in candles offers promise for a much more modern energy challenge--storing massive amounts of energy to be fed into the electric grid as the need arises.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have shown that low-cost organic compounds hold promise for storing grid energy. Common fluorenone, a bright yellow powder, was at first a reluctant participant, but with enough chemical persuasion has proven to be a potent partner for energy storage in flow battery systems, large systems that store energy for the grid.

Development of such storage is critical. When the grid goes offline due to severe weather, for instance, the large batteries under ...

2021-05-20

Wherever ecologists look, from tropical forests to tundra, ecosystems are being transformed by human land use and climate change. A hallmark of human impacts is that the rates of change in ecosystems are accelerating worldwide.

Surprisingly, a new study, published today in Science, found that these rates of ecological change began to speed up many thousands of years ago. "What we see today is just the tip of the iceberg" noted co-lead author Ondrej Mottl from the University of Bergen (UiB). "The accelerations we see during the industrial revolution and modern periods have a deep-rooted history stretching back in time."

Using a global network of over 1,000 fossil pollen records, the team found - and expected to find - a first peak ...

2021-05-20

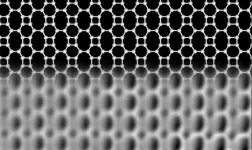

Carbon exists in various forms. In addition to diamond and graphite, there are recently discovered forms with astonishing properties. For example graphene, with a thickness of just one atomic layer, is the thinnest known material, and its unusual properties make it an extremely exciting candidate for applications like future electronics and high-tech engineering. In graphene, each carbon atom is linked to three neighbours, forming hexagons arranged in a honeycomb network. Theoretical studies have shown that carbon atoms can also arrange in other flat network patterns, while still binding to three neighbours, but none of these predicted networks had been realized until now.

Researchers at the University of Marburg ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] What makes some oysters more resilient than others?

New research by Louisiana State University biologists offers insight into this commercially important species