(Press-News.org) Nearly half a billion people on the planet have diabetes, but most of them aren't getting the kind of care that could make their lives healthier, longer and more productive, according to a new global study of data from people with the condition.

Many don't even know they have the condition.

Only 1 in 10 people with diabetes in the 55 low- and middle-income countries studied receive the type of comprehensive care that's been proven to reduce diabetes-related problems, according to the new findings published in Lancet Healthy Longevity.

That comprehensive package of care - low-cost medicines to reduce blood sugar, blood pressure and cholesterol levels; and counseling on diet, exercise and weight - can help lower the health risks of under-treated diabetes. Those risks include future heart attacks, strokes, nerve damage, blindness, amputations and other disabling or fatal conditions.

The new study, led by physicians at the University of Michigan and Brigham and Women's Hospital with a global team of partners, draws on data from standardized household studies, to allow for apples-to-apples comparisons between countries and regions.

The authors analyzed data from surveys, examinations and tests of more than 680,000 people between the ages of 25 and 64 worldwide conducted in recent years. More than 37,000 of them had diabetes; more than half of them hadn't been formally diagnosed yet, but had a key biomarker of elevated blood sugar.

The researchers have provided their findings to the World Health Organization, which is developing efforts to scale up delivery of evidence-based diabetes care globally as part of an initiative known as the Global Diabetes Compact. The forms of diabetes-related care used in the study are all included in the 2020 WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions.

"Diabetes continues to explode everywhere, in every country, and 80% of people with it live in these low- and middle-income countries," says David Flood, M.D., M.Sc., lead author and a National Clinician Scholar at the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. "It confers a high risk of complications such as including heart attacks, blindness, and strokes. We can prevent these complications with comprehensive diabetes treatment, and we need to make sure people around the world can access treatment."

Flood worked with senior author Jennifer Manne-Goehler, M.D., Sc.D., of Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Medical Practice Evaluation Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, to lead the analysis of detailed global data.

Key findings

In addition to the main finding that 90% of the people with diabetes studied weren't getting access to all six components of effective diabetes care, the study also finds major gaps in specific care.

For instance, while about half of all people with diabetes were taking a drug to lower their blood sugar, and 41% were taking a drug to lower their blood pressure, only 6.3% were receiving cholesterol-lowering medications.

These findings show the need to scale-up proven treatment not only to lower glucose but also to address cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension and high cholesterol, in people with diabetes.

Less than a third had access to counseling on diet and exercise, which can help guide people with diabetes to adopt habits that can control their health risks further.

Even when the authors focused on the people who had already received a formal diagnosis of diabetes, they found that 85% were taking a medicine to lower blood sugar, 57% were taking a blood pressure medication, but only 9% were taking something to control their cholesterol. Nearly 74% had received diet-related counseling, and just under 66% had received exercise and weight counseling.

Taken together, less than one in five people with previously diagnosed diabetes were getting the full package of evidence-based care.

Relationship to national income and personal characteristics

In general, the study finds that people were less likely to get evidence-based diabetes care the lower the average income of the country and region they lived in. That's based on a model that the authors created using economic and demographic data about the countries that were included in the study.

The nations in the Oceania region of the Pacific had the highest prevalence of diabetes - both diagnosed and undiagnosed - but the lowest rates of diabetes-related care.

But there were exceptions where low-income countries had higher-than-expected rates of good diabetes care, says Flood, citing the example of Costa Rica. And in general, the Latin America and Caribbean region was second only to Oceania in diabetes prevalence, but had much higher levels of care.

Focusing on what countries with outsize achievements in diabetes care are doing well could provide valuable insights for improving care elsewhere, the authors say. That even includes informing care in high-income countries like the United States, which does not consistently deliver evidence-based care to people with diabetes.

The study also shines a light on the variation between countries and regions in the percentage of cases of diabetes that have been diagnosed. Improve reliable access to diabetes diagnostic technologies is important in leading more people to obtain preventive care and counseling.

Women, people with higher levels of education and higher personal wealth, and people who are older or had high body mass index were more likely to be receiving evidence-based diabetes care. Diabetes in people with "normal" BMI is not uncommon in low- and middle-income countries, suggesting more need to focus on these individuals, the authors say.

The fact that diabetes-related medications are available at very low cost, and that individuals can reduce their risk through lifestyle changes, mean that cost should not be a major barrier, says Flood. In fact, studies have shown the medications to be cost-effective, meaning that the cost of their early and consistent use is outweighed by the savings on other types of care later.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Flood, who is a clinical lecturer in hospital medicine at Michigan Medicine, U-M's academic medical center, the study team includes two others from U-M: Michele Heisler, M.D., M.P.A., a professor of internal medicine and member of IHPI, and Matthew Dunn, a student at the U-M School of Public Health. The study was funded by the National Clinician Scholars Program at IHPI, and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Harvard Catalyst, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Business shutdowns reduce COVID-19 deaths, though with rapidly diminishing returns, with study of Italian lockdowns estimating they saved over 9,400 lives in under a month.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: Closed for business: The mortality impact of business closures during the Covid-19 pandemic

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0251373

...

Plant diseases don't stop at national borders and miles of oceans don't prevent their spread, either. That's why plant disease surveillance, improved detection systems, and global predictive disease modeling are necessary to mitigate future disease outbreaks and protect the global food supply, according to a team of researchers in a new commentary published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The idea is to "detect these plant disease outbreak sources early and stop the spread before it becomes a pandemic," says lead-author Jean Ristaino, William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Plant Pathology at North Carolina State University. Once an epidemic occurs it is difficult to control, Ristaino says, likening the effort to the one undertaken ...

Neurotic personalities found the pandemic most traumatic, while agreeable and conscientious personalities offered protection from the pandemic's negative impacts.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: Which personality traits can mitigate the impact of the pandemic? Assessment of the relationship between personality traits and traumatic events in the COVID-19 pandemic as mediated by defense mechanisms

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0251984

...

Simon Fraser University researchers have validated a faster, cheaper COVID-19 test that could kickstart the expansion of more widespread rapid testing. Study results have been published in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

"This research offers a cheaper, faster alternative to the most reliable and sensitive test currently used worldwide, without sacrificing sensitivity and reproducibility," says molecular biology and biochemistry professor Peter Unrau, who led the team evaluating the COVID-19 test kit.

The researchers suggest the test could be deployed in remote locations, clinics and airports due to its ease of use and portability.

The microchip real-time PCR test can provide ...

To meet soaring demand for lightning-quick mobile technology, each year tech giants create faster, more powerful devices with longer-lasting battery power than previous models.

A major reason companies like Apple and Samsung can miraculously pull this off year after year is because engineers and researchers around the world are designing increasingly power-efficient microchips that still deliver high speeds.

To that end, researchers led by a team at Brigham Young University have just built the world's most power-efficient high-speed analog-to-digital converter (ADC) microchip. An ADC is a tiny piece of technology present in almost every electronic piece of equipment that converts analog ...

For decades scientists have been puzzled by the formation of rare hyper-enriched gold deposits in places like Ballarat in Australia, Serra Palada in Brazil, and Red Lake in Ontario. While such deposits typically form over tens to hundreds of thousands of years, these "ultrahigh-grade" deposits can form in years, month, or even days. So how do they form so quickly?

Studying examples of these deposits from the Brucejack Mine in northwestern British Columbia, McGill Professor Anthony Williams-Jones of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and PhD student Duncan McLeish have discovered that these gold deposits form much like soured milk. When milk goes sour, the butterfat particles clump together to form a jelly.

Q&A with Anthony Williams-Jones and Duncan McLeish

What did you ...

A team of researchers led by scientists at UC Santa Cruz analyzed data from 3,212 camera traps to show how human disturbance could be shifting the makeup of mammal communities across North America.

The new study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, builds upon the team's prior work observing how wildlife in the Santa Cruz Mountains respond to human disturbance. Local observations, for example, have shown that species like pumas and bobcats are less likely to be active in areas where humans are present, while deer and wood rats become bolder and more active. But it's difficult to generalize findings like these across larger geographic areas because human-wildlife interactions are often regionally unique.

So, to get a continent-wide ...

Free access to essential medicines increases patient adherence to taking medication by 35 per cent and reduces total health spending by an average of over $1,000 per patient per year, according to a two-year study that tested the effects of providing patients with free and convenient access to a carefully selected set of medications.

The findings, published May 21 in PLOS Medicine, come as advocates urge Canada to carve a path toward single-payer, public pharmacare. Canada is the only country with universal healthcare that does not have a universal pharmacare program.

A group of researchers led by St. Michael's Hospital of Unity Health ...

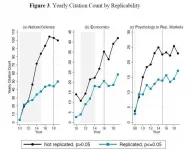

Papers in leading psychology, economic and science journals that fail to replicate and therefore are less likely to be true are often the most cited papers in academic research, according to a new study by the University of California San Diego's Rady School of Management.

Published in Science Advances, the paper explores the ongoing "replication crisis" in which researchers have discovered that many findings in the fields of social sciences and medicine don't hold up when other researchers try to repeat the experiments.

The paper reveals that findings from studies that ...

The human body is constantly exposed to various environmental actors, from viruses to bacteria to fungi, but most of these microbial organisms provoke little or no response from our skin, which is charged with monitoring and protecting from external dangers.

Until now, researchers weren't quite sure how that happened -- and why our skin wasn't constantly alarmed and inflamed.

In a study published May 21, 2021 in Science Immunology, scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine identify and describe two enzymes responsible for protecting our skin and body's overall health from countless potential microbial intruders. These enzymes, called histone deacetylases (HDACs), inhibit the body's inflammatory response in the skin.

"We have figured ...