(Press-News.org) People don't gain or lose weight because they live near a fast-food restaurant or supermarket, according to a new study led by the University of Washington. And, living in a more "walkable", dense neighborhood likely only has a small impact on weight.

These "built-environment" amenities have been seen in past research as essential contributors to losing weight or tending toward obesity. The idea appears obvious: If you live next to a fast-food restaurant, you'll eat there more and thus gain weight. Or, if you have a supermarket nearby, you'll shop there, eat healthier and thus lose weight. Live in a neighborhood that makes walking and biking easier and you'll get out, exercise more and burn more calories.

The new study based on anonymized medical records from more than 100,000 Kaiser Permanente Washington patients did not find that living near supermarkets or fast-food restaurant had any impact on weight. However, urban density, such as the number of houses in a given neighborhood, which is closely linked to neighborhood "walkability" appears to be the strongest element of the built environment linked to change in body weight over time.

"There's a lot of prior work that has suggested that living close to a supermarket might lead to lower weight gain or more weight loss, while living close to lots of fast-food restaurants might lead to weight gain," said James Buszkiewicz, lead author of the study and a research scientist in the UW School of Public Health. "Our analyses of the food environment and density together suggests that the more people there are in an area -- higher density -- the more supermarkets and fast-food restaurants are located there. And we found that density matters to weight gain, but not proximity to fast food or supermarkets. So, that seems to suggest that those other studies were likely observing a false signal."

The UW-led study, published earlier this month in the International Journal of Obesity, found that people living in neighborhoods with higher residential and population density weigh less and have less obesity than people living in less-populated areas. And that didn't change over a five-year period of study.

"On the whole, when thinking about ways to curb the obesity epidemic, our study suggests there's likely no simple fix from the built environment, like putting in a playground or supermarket," said Buszkiewicz, who did his research for the study while a graduate student in the UW Department of Epidemiology.

Rather than "something magical about the built environment itself" influencing the weight of those individuals, Buszkiewicz said, community-level differences in obesity are more likely driven by systematic factors other than the built environment -- such as income inequality, which is often the determining factor of where people can afford to live and whether they can afford to move.

"Whether you can afford to eat a healthy diet or to have the time to exercise, those factors probably outweigh the things we're seeing in terms of the built environment effect," he said.

The researchers used the Kaiser Permanente Washington records to gather body weight measurements several times over a five-year period. They also used geocodable addresses to establish neighborhood details, including property values to help establish socioeconomic status, residential unit density, population density, road intersection density, and counts of supermarkets and fast-food restaurants accessible within a short walk or drive.

"This study really leverages the power of big data," said Dr. David Arterburn, co-author and senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. "Our use of anonymized health care records allows us to answer important questions about environmental contributions to obesity that would have been impossible in the past."

This study is part of a 12-year, joint UW and Kaiser Permanente Washington research project called Moving to Health. The goal of the study, according to the UW's project website, is to provide population-based, comprehensive, rigorous evidence for policymakers, developers and consumers regarding the features of the built environment that are most strongly associated with risk of obesity and diabetes.

"Our next goal is to better understand what happens when people move their primary residence from one neighborhood to another," Arterburn said. "When our neighborhood characteristics change rapidly -- such as moving to a much more walkable residential area -- does that have an important effect on our body weight?"

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Jennifer Bobb, Andrea Cook, Maricela Cruz, Paula Lozano, Dori Rosenberg, Mary Kay Theis and Jane Anau at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute; Anne Vernez Moudon, UW Urban Form Lab, College of Built Environments; Stephen Mooney, UW Department of Epidemiology; Philip Hurvitz, UW Urban Form Lab and Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology; Shilpi Gupta and Adam Drewnowski, UW Center for Public Health Nutrition and Department of Epidemiology. This research manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: 1 R01 DK 114196, 5 R01 DK076608, and 4 R00LM012868.

For more information, contact Buszkiewicz at buszkiew@uw.edu and Caroline Liou Caroline.X.Liou@kp.org

Researchers at the Karolinska Institutet, University of Oxford and University of Copenhagen have shown that elevated levels of lipids known as ceramides can be associated with a ten-fold higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease. Treatment with liraglutide could keep the ceramide levels in check, compared with placebo. The results have been published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Approximately 16 percent of the Swedish population suffers from obesity (BMI over 30), which is one of the greatest risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction and stroke. The World Health ...

Has your heart ever started to race at the thought of an upcoming deadline for work? Or has the sight of an unknown object in a dark room made you jump? Well, you can probably thank your amygdala for that.

The small almond-shaped brain structure is central to how we perceive and process fear. As we start to learn to associate fear with cues in our environment, neuronal connections within the amygdala are dynamically altered in a process called synaptic plasticity. Although this physiological mechanism is important for facilitating fear learning, it has mostly been studied in the context of excitatory neurons within the amygdala. Far less is known about the role inhibitory cells ...

CHICAGO, May 24, 2021--More than a year after COVID-19 appeared in the U.S., dentists continue to have a lower infection rate than other front-line health professionals, such as nurses and physicians, according to a study published online ahead of the June print issue in the Journal of the American Dental Association. The study, "COVID19 among Dentists in the U.S. and Associated Infection Control: a six-month longitudinal study," is based on data collected June 9 - Nov. 13, 2020.

According to the study, based on the number of dentists with confirmed or probable COVID-19 infections over more than six months, the cumulative infection rate for U.S. dentists is 2.6%. The monthly incidence ...

Researchers at Lund University in Sweden have developed an algorithm that combines data from a simple blood test and brief memory tests, to predict with great accuracy who will develop Alzheimer's disease in the future. The findings are published in Nature Medicine.

Approximately 20-30% of patients with Alzheimer's disease are wrongly diagnosed within specialist healthcare, and diagnostic work-up is even more difficult in primary care. Accuracy can be significantly improved by measuring the proteins tau and beta-amyloid via a spinal fluid sample, or PET scan. However, those methods are expensive and only available at a relatively few specialized memory clinics worldwide. Early and accurate ...

Ecology, the field of biology devoted to the study of organisms and their natural environments, needs to account for the historical legacy of colonialism that has shaped people and the natural world, researchers argued in a new perspective in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

To make ecology more inclusive of the world's diverse people and cultures living in diverse ecosystems, researchers from University of Cape Town, North West University in South Africa and North Carolina State University proposed five strategies to untangle the impacts of colonialism on research and thinking in the field today.

"There are significant biases in our understanding ...

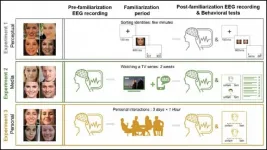

The neural representation of a familiar face strengthens faster when you see someone in person, according to a new study published in JNeurosci.

The brain loves faces -- there's even an interconnected network of brain areas dedicated to face-processing. Despite all the research on how the brain sees faces, little is known about how the neural representation of a face changes as it becomes familiar.

To track how familiarity brain signals change, Ambrus et al. measured participants' brain activity with EEG before and after getting to know different ...

A strange phenomenon happens with modern blue whales, humpback whales and gray whales: they have teeth in the womb but are born toothless. Replacing the teeth is baleen, a series of plates composed of thin, hair- and fingernail-like structures growing from the roof of their mouths that act as a sieve for filter feeding small fish and tiny shrimp-like krill.

The disappearing embryonic teeth are testament to an evolutionary history from ancient whales that had teeth and consumed larger prey. Modern baleen whales on the other hand use their fringed baleen to strain their miniscule prey from water, hence the term filter feeding.

A new study that utilized high-resolution computed tomography (CT) to ...

East Hanover, NJ. May 24, 2021. A recent qualitative study of rehabilitation professionals caring for people with spatial neglect enabled researchers to identify interventions to improve rehabilitation outcomes. Experts reported that implementation of spatial neglect care depends on interventions involving family support and training, promotion of interdisciplinary collaboration, development of interprofessional vocabulary, and continuous treatment and follow-up assessment through care transitions.

The article, "Barriers and Facilitators to Rehabilitation Care of Individuals with Spatial ...

Scientists at the University of York have made significant progress in the development of a nasal spray treatment for patients with Parkinson's disease.

Researchers have developed a new gel that can adhere to tissue inside the nose alongside the drug levodopa, helping deliver treatment directly to the brain.

Levodopa is converted to dopamine in the brain, which makes-up for the deficit of dopamine-producing cells in Parkinson's patients, and helps treat the symptoms of the disease. Over extended periods of time, however, levodopa becomes less effective, and increased doses are needed.

Professor David Smith, from the ...

Extra funding should be made available for early years care in the wake of the pandemic, researchers say.

Experts at the University of Leeds, University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University have made the call after assessing the benefits of early childhood education and care (ECEC) for children under three during COVID-19.

They found children who attended childcare outside the home throughout the first UK lockdown made greater gains in language and thinking skills, particularly if they were from less advantaged backgrounds.

And now they are making several policy recommendations ...