Can antibiotics treat human diseases in addition to bacterial infections?

UIC researchers prove that drugs designed for bacteria have potential to act on human cells

2021-05-24

(Press-News.org) According to researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago, the antibiotics used to treat common bacterial infections, like pneumonia and sinusitis, may also be used to treat human diseases, like cancer. Theoretically, at least.

As outlined in a new Nature Communications study, the UIC College of Pharmacy team has shown in laboratory experiments that eukaryotic ribosomes can be modified to respond to antibiotics in the same way that prokaryotic ribosomes do.

Fungi, plants, and animals -- like humans -- are eukaryotes; they are made up of cells that have a clearly defined nucleus. Bacteria, on the other hand, are prokaryotes. They are made up of cells, which do not have a nucleus and have a different structure, size and properties. The ribosomes of eukaryotic and procaryotic cells, which are responsible for the protein synthesis needed for cell growth and reproduction, are also different.

"Some antibiotics, used for treating bacterial infections, work in an interesting way. They bind to the ribosome of bacterial cells and very selectively inhibit protein synthesis. Some proteins are allowed to be made, but others are not," said Alexander Mankin, the Alexander Neyfakh Professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy at the UIC College of Pharmacy and senior author of the study. "Without these proteins being made, bacteria die."

When people use antibiotics to treat an infection, the cells of the patient are not affected because the drugs are not designed to bind to the differently shaped ribosomes of eukaryotic cells.

"Because there are many human diseases caused by the expression of unwanted proteins -- this is common in many types of cancer or neurodegenerative diseases, for example -- we wanted to know if it would be possible to use an antibiotic to stop a human cell from making the unwanted proteins, and only the unwanted proteins," Mankin said.

To answer this question, Mankin and study first author Maxim Svetlov, research assistant professor with the department of pharmaceutical sciences, looked to yeast, a eukaryote with cells similar to human cells.

The research team, which included partners from Germany and Switzerland, performed a "cool trick," Mankin said. "We engineered the yeast ribosome to be more bacteria-like."

Mankin and Svetlov's team used biochemistry and fine genetics to change one nucleotide of more than 7,000 in yeast ribosomal RNA, which was enough to make a macrolide antibiotic -- a common class of antibiotics that works by binding to bacterial ribosomes -- act on the yeast ribosome. Using this yeast model, the researchers applied genomic profiling and high-resolution structural analysis to understand how every protein in the cell is synthesized and how the macrolide interacts with the yeast ribosome.

"Through this analysis, we understood that depending on a protein's specific genetic signature -- the presence of a 'good' or 'bad' sequence -- the macrolide can stop its production on the eukaryotic ribosome or not," Mankin said. "This showed us, conceptually, that antibiotics can be used to selectively inhibit protein synthesis in human cells and used to treat human disorders caused by 'bad' proteins."

The experiments of the UIC researchers provide a staging ground for further studies. "Now that we know the concepts work, we can look for antibiotics that are capable of binding in the unmodified eukaryotic ribosomes and optimize them to inhibit only those proteins that are bad for a human," Mankin said.

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors of the study are Dorota Klepacki and Nora Vázquez-Laslop of UIC; Timm Koller and Daniel Wilson of the University of Hamburg; Sezen Meydan and Nicholas Guydosh of the National Institutes of Health; and Norbert Polacek and Vaishnavi Shankar of the University of Bern.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35 GM127134, DK075132, 1FI2GM137845), the German Research Foundation (WI3285/6-1), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_166527).

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-24

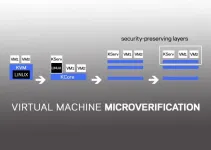

New York, NY--May 24, 2021--Whenever you buy something on Amazon, your customer data is automatically updated and stored on thousands of virtual machines in the cloud. For businesses like Amazon, ensuring the safety and security of the data of its millions of customers is essential. This is true for large and small organizations alike. But up to now, there has been no way to guarantee that a software system is secure from bugs, hackers, and vulnerabilities.

Columbia Engineering researchers may have solved this security issue. They have developed SeKVM, the ...

2021-05-24

MISSOULA, Mont., May 24, 2021 -- Scientists from the Rocky Mountain Research Station collaborated to explore how research and management can confront increasing uncertainty due to climate change, invasive species, and land use conversion.

Wildland management and policy have long depended on the idea that ecosystems are fundamentally static, and periodic events like droughts are just temporary detours from a larger, stable equilibrium. However, ecosystems are currently changing at unprecedented rates. For example, bark beetle infestations, droughts, and severe wildfires have killed large numbers of trees across the western ...

2021-05-24

A new research, carried out by the D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR) and the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), has shown for the first time that storytelling is capable of providing physiological and emotional benefits to children in Intensive Care Units (ICUs). The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the official scientific journal of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S. The study was led by Guilherme Brockington, PhD, from UFABC, and Jorge Moll, MD, PhD, from IDOR.

"During storytelling, something happens that we call 'narrative ...

2021-05-24

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues from Russia and the US have shown that the two components of the bacterial CRISPR-Cas immunity system, one that destroys foreign genetic elements such as viruses and another that creates "memories" of foreign genetic elements by storing fragments of their DNA in a special location of bacterial genome, are physically linked. This link helps bacteria to efficiently update their immune memory when infected by mutant viruses that learned to evade the CRISPR-Cas defense. The paper was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

CRISPR-Cas, a defense mechanism that provides bacteria with resistance to their viruses (bacteriophages), destroys DNA from ...

2021-05-24

LOS ANGELES (May 24, 2021) -- Today, The Lundquist Institute announced that Wei Yan, MD, PhD, and his research group have solved a longstanding mystery and scientific debate about the mechanism underlying the gamete and embryo transport within the Fallopian tube. Using a mouse model where the animals lacked motile cilia in the oviduct, Dr. Yan's group demonstrated that motile cilia in the very distal end of the Fallopian tube, called infundibulum, are essential for oocyte pickup. Disruptions of the ciliary structure and/or beating patterns lead to failure in oocyte pickup and consequently, a loss of female fertility. Interestingly, motile cilia in other parts of the oviduct can facilitate sperm ...

2021-05-24

Hearing loss is a disability that affects approximately 5% of the world's population. Clinically determining the exact site of the lesion is critical for choosing a proper treatment for hearing loss. For example, the subjects with damage in sound conduction or mild outer hair cell damage would benefit from hearing aids, while those with significant damage to outer or inner hair cells would benefit from the cochlear implant. On the other hand, the subjects with impairments in more central structures such as the cochlear nerve, brainstem, or brain do not benefit from either hearing aids or cochlear implants. However, the role of impairments in cochlear glial cells in hearing loss is not as well known. While it is known that connexin channels in cochlear glial ...

2021-05-24

Scientists at UC San Diego, San Diego State University and colleagues find that extreme heat and elevated ozone levels, often jointly present during California summers, affect certain ZIP codes more than others.

Those areas across the state most adversely affected tend to be poorer areas with greater numbers of unemployed people and more car traffic. The science team based this finding on data about the elevated numbers of people sent to the hospital for pulmonary distress and respiratory infections in lower-income ZIP codes.

The study identified hotspots throughout ...

2021-05-24

In 2018, the Camp Fire ripped through the town of Paradise, California at an unprecedented rate. Officials had prepared an evacuation plan that required 3 hours to get residents to safety. The fire, bigger and faster than ever before, spread to the community in only 90 minutes.

As climate change intensifies, wildfires in the West are behaving in ways that were unimaginable in the past--and the common disaster response approaches are woefully unprepared for this new reality. In a recent study, a team of researchers led by the University of Utah proposed a framework for simulating dire scenarios, which the authors define as scenarios where there is less time to ...

2021-05-24

Mosquitoes are one of humanity's greatest nemeses, estimated to spread infections to nearly 700 million people per year and cause more than one million deaths.

UC Santa Barbara Distinguished Professor Craig Montell has made a breakthrough in one technique for controlling populations of Aedes aegypti, a mosquito that transmits dengue, yellow fever, Zika and other viruses. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, documents the first use of CRISPER/Cas9 gene editing to target a specific gene tied to fertility in male mosquitoes. The researchers were then able to discern how this mutation can suppress ...

2021-05-24

A study conducted by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory reveals that the use of corn ethanol is reducing the carbon footprint and diminishing greenhouse gases.

The study, recently published in Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, analyzes corn ethanol production in the United States from 2005 to 2019, when production more than quadrupled. Scientists assessed corn ethanol's greenhouse gas (GHG) emission intensity (sometimes known as carbon intensity, or CI) during that period and found a 23% reduction in CI.

According ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Can antibiotics treat human diseases in addition to bacterial infections?

UIC researchers prove that drugs designed for bacteria have potential to act on human cells