(Press-News.org) A team of international researchers has found that the Tsimane indigenous people of the Bolivian Amazon experience less brain atrophy than their American and European peers. The decrease in their brain volumes with age is 70% slower than in Western populations. Accelerated brain volume loss can be a sign of dementia.

The study was published May 26, 2021 in the Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences.

Although people in industrialized nations have access to modern medical care, they are more sedentary and eat a diet high in saturated fats. In contrast, the Tsimane have little or no access to health care but are extremely physically active and consume a high-fiber diet that includes vegetables, fish and lean meat.

"The Tsimane have provided us with an amazing natural experiment on the potentially detrimental effects of modern lifestyles on our health," said study author Andrei Irimia, an assistant professor of gerontology, neuroscience and biomedical engineering at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering. "These findings suggest that brain atrophy may be slowed substantially by the same lifestyle factors associated with very low risk of heart disease."

The researchers enrolled 746 Tsimane adults, ages 40 to 94, in their study. To acquire brain scans, they provided transportation for the participants from their remote villages to Trinidad, Bolivia, the closest town with CT scanning equipment. That journey could last as long as two full days with travel by river and road.

The team used the scans to calculate brain volumes and then examined their association with age for Tsimane. Next, they compared these results to those in three industrialized populations in the U.S. and Europe.

The scientists found that the difference in brain volumes between middle age and old age is 70% smaller in Tsimane than in Western populations. This suggests that the Tsimane's brains likely experience far less brain atrophy than Westerners as they age; atrophy is correlated with risk of cognitive impairment, functional decline and dementia.

The researchers note that the Tsimane have high levels of inflammation, which is typically associated with brain atrophy in Westerners. But their study suggests that high inflammation does not have a pronounced effect upon Tsimane brains.

According to the study authors, the Tsimane's low cardiovascular risks may outweigh their infection-driven inflammatory risk, raising new questions about the causes of dementia. One possible reason is that, in Westerners, inflammation is associated with obesity and metabolic causes whereas, in the Tsimane, it is driven by respiratory, gastrointestinal, and parasitic infections. Infectious diseases are the most prominent cause of death among the Tsimane.

"Our sedentary lifestyle and diet rich in sugars and fats may be accelerating the loss of brain tissue with age and making us more vulnerable to diseases such as Alzheimer's," said study author Hillard Kaplan, a professor of health economics and anthropology at Chapman University who has studied the Tsimane for nearly two decades. "The Tsimane can serve as a baseline for healthy brain aging."

Healthier hearts and -- new research shows -- healthier brains

The indigenous Tsimane people captured scientists' -- and the world's -- attention when an earlier study found them to have extraordinarily healthy hearts in older age. That prior study, published by the Lancet in 2017, showed that Tsimane have the lowest prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis of any population known to science and that they have few cardiovascular disease risk factors. The very low rate of heart disease among the roughly 16,000 Tsimane is very likely related to their pre-industrial subsistence lifestyle of hunting, gathering, fishing, and farming.

"This study demonstrates that the Tsimane stand out not only in terms of heart health, but brain health as well," Kaplan said. "The findings suggest ample opportunities for interventions to improve brain health, even in populations with high levels of inflammation."

INFORMATION:

About the study

In addition to Irimia and Kaplan, study authors include Nikhil N. Chaudhari, David J. Robles, Kenneth A. Rostowsky, Alexander S. Maher, Nahian F. Chowdhury, Maria Calvillo, Van Ngo, Margaret Gatz, Wendy J. Mack and Caleb E. Finch (USC), E. Meng Law (Monash University), M. Linda Sutherland, James D. Sutherland and Gregory S. Thomas (MemorialCare Heart and Vascular Institute), Christopher J. Rowan (University of Nevada, Reno), L. Samuel Wann (Ascension Healthcare), Adel H. Allam (Al-Alzhar University, Egypt), Randall C. Thompson (St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute), David E. Michalik (University of California, Irvine), Daniel K. Cummings and Edmond Seabright and Paul L. Hooper (University of New Mexico), Sarah Alami and Michael D. Gurven (University of California, Santa Barbara), Angela R. Garcia and Benjamin C. Trumble (Arizona State University, Tempe) and Jonathan Stieglitz (Institute for Advanced Study, Toulouse, France).

Research funding was provided by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (grant RF1 AG 054442) and the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse and the French National Research Agency under the Investments for the Future (Investissements d'Avenir) program (grant ANR-17-EURE-0010).

UC San Francisco researchers have found a way to double doctors' accuracy in detecting the vast majority of complex fetal heart defects in utero - when interventions could either correct them or greatly improve a child's chance of survival - by combining routine ultrasound imaging with machine-learning computer tools.

The team, led by UCSF cardiologist Rima Arnaout, MD, trained a group of machine-learning models to mimic the tasks that clinicians follow in diagnosing complex congenital heart disease (CHD). Worldwide, humans detect as few as 30 to 50 percent of these conditions before birth. However, the combination of human-performed ultrasound ...

University of Virginia School of Medicine scientists have developed important new resources that will aid the battle against cancer and advance cutting-edge genomics research.

UVA's Chongzhi Zang, PhD, and his colleagues and students have developed a new computational method to map the folding patterns of our chromosomes in three dimensions from experimental data. This is important because the configuration of genetic material inside our chromosomes actually affects how our genes work. In cancer, that configuration can go wrong, so scientists want to understand ...

Hundreds of antibiotic resistant genes found in the gastrointestinal tracts of Danish infants

Danish one-year-olds carry several hundred antibiotic resistant genes in their bacterial gut flora according to a new study from the University of Copenhagen. The presence of these genes is partly attributable to antibiotic use among mothers during pregnancy.

An estimated 700,000 people die every year from antibiotic resistant bacterial infections and diseases. The WHO expects this figure to multiply greatly in coming decades. To study how antibiotic resistance occurs in humans' ...

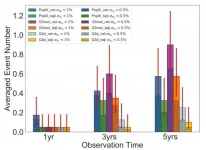

The Hubble parameter is one of the central parameters in the modern cosmology. Their values inferred from the late-time observations are systematically higher than those from the early-time measurements by about 10%. This is called the "Hubble tension". To come to a robust conclusion, independent probes with accuracy at percent levels are crucial. With the self-calibration by the theory of general relativity, gravitational waves from compact binary coalescence open a completely novel observational window for Hubble parameter determination. Hence, it can shed some light on the Hubble tension. Depends on whether being associated with ...

A new rapid coronavirus test developed by KAUST scientists can deliver highly accurate results in less than 15 minutes.

The diagnostic, which brings together electrochemical biosensors with engineered protein constructs, allows clinicians to quickly detect bits of the virus with a precision previously only possible with slower genetic techniques. The entire set-up can work at the point of patient care on unprocessed blood or saliva samples; no laborious sample preparation or centralized diagnostic laboratory is required.

"The combination of state-of-the-art ...

Dust storms are often defined as catastrophic weather events where large amounts of dust particles are raised and transported by strong winds, characterized by weak horizontal visibility (< 1 km), suddenness, short duration, and severe destruction. Over the past few decades, the observed dust storms in northern China showed generally decreasing trends (Fig. 2), which could have made the dust storms "out of sight" of the public gradually. Yet a most recent strong dust storm event originated from Mongolia since mid-March this year exerted serious impacts on most areas in northern China, ...

RICHLAND, Wash.--As the Clean Energy Transformation Act drives Washington state toward carbon-free electricity, a new energy landscape is taking shape. Alongside renewable energy sources, a new report finds small modular reactors are poised to play an integral role in the state's emerging clean energy future.

The technology could help fill a power source gap soon to be left by carbon-emitting resources like coal and natural gas, which will be phased out in coming years, according to a report composed by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"Nuclear energy is a reliable source of baseload electricity," said PNNL's ...

Modern genetic research often works with what are known as reference genomes. Such a genome comprises data from DNA sequences that scientists have assembled as a representative example of the genetic makeup of a species.

To create the reference genome, researchers generally use DNA sequences from a single or a few individuals, which can poorly represent the complete genomic diversity of individuals or sub-populations. The result is that a reference does not always correspond exactly to the set of genes of a specific individual.

Until a few years ago, it was very laborious, expensive and time-consuming to generate ...

Many eye diseases are associated with a restricted blood supply, known as ischaemia, which can lead to blindness. The role of the protein tenascin-C, an extracellular matrix component, in retinal ischaemia was investigated in mice by researchers from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB). They showed that tenascin-C plays a crucial role in damaging the cells responsible for vision following ischaemia. The results were published online by the team in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience on 20 May 2021.

As part of the research, the team around Dr. Susanne Wiemann and Dr. Jacqueline Reinhard from the Department of Cell Morphology and Molecular Neurobiology at RUB collaborated with Professor Stephanie Joachim's research group from ...

Included in the vast fallout stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists are paying closer attention to microbial infections and how life forms defend against attacks from pathogens.

Research led by University of California San Diego scientists has shed new light on the complex dynamics involved in how organisms sense that an infection is taking place.

UC San Diego Assistant Project Scientist Eillen Tecle in Professor Emily Troemel's laboratory (Division of Biological Sciences) led research focusing on how cells that are not part of the conventional immune system respond to infections when pathogens attack. Scientists have conducted extensive research on so-called "professional" immune cells that are defensive specialists. Much less is known about how "non-professional" cells ...