(Press-News.org) New research published in Nature provides a powerful yet surprisingly simple way to determine the number of visitors to any location in a city.

Scientists* from the Santa Fe Institute, MIT, and ETH Zürich have discovered and developed a scaling law that governs the number of visitors to any location based on how far they are traveling and how often they are visiting. The visitation law opens up unprecedented possibilities for accurately predicting flows between locations, which could ultimately have applications in everything from city planning to preventing the spread of the next major pandemic.

"Imagine you are standing on a busy plaza, say in Boston, and you see people coming and going. This may look pretty random and chaotic, but the law shows that these movements are surprisingly structured and predictable. It basically tells you how many of these people are coming from 1, 2 or 10 kilometers away and how many are visiting once, twice or 10 times a month", says lead author Markus Schläpfer of ETH Zurich's Future Cities Laboratory. "And the best part is that this same regularity holds not only in Boston, but across cities worldwide."

The researchers' findings are a result of an analysis of mobile phone data from millions of anonymized cell phone users in highly diverse urban regions across the world, including Greater Boston in the United States, Lisbon in Europe, Singapore in Asia, and Dakar in Africa. Schläpfer began the analysis and development of the theory while he was a post-doctoral fellow at the Santa Fe Institute working together with senior author Geoffrey West, a physicist who leads the Cities, Scaling, and Sustainability project. It was later extended to include researchers at the MIT Sensible Cities Laboratory under the leadership of the architect Carlo Ratti.

Universally, they found that the number of visitors to any urban location scales as the inverse square of both travel distance from home and the visitation frequency. Like the gravitational pull of a large planet, an attractive city plaza with fine museums and famous shops draws relatively more visitors from more distant locations, though less frequently than those coming from nearby locations, their relative numbers being predictably determined by the inverse square law. A further surprising consequence of this new visitation law is that the same number of people visit the location whether they are coming from, say, 10km away 3 times a week, or from 3km away 10 times a week.

While previous research has used mobile phone data to study human movement from the perspectives of individual people -- where they go, when, and how often -- this is the first systematic study to focus on the frequency of visits from the perspective of places, using mobile phone data to understand the relative attractiveness or utility of an urban area.

"There's an optimization problem going on here in terms of the amount of energy people are using, the distance they're travelling, and the number of trips they're making," says Geoffrey West. "When we travel for leisure we choose our destinations. During everyday life, those choices are more forced because we have to go to work, say, five times a week, pick up the kids two times, etc. But there's this remarkable conservation inherent in the visitation law -- namely, the average amount of energy that people allocate to travel is the same whether they try to do it across different distances or at different frequencies."

Schläpfer says the new paper can give urban planners "a baseline for understanding which locations in their cities are over- or under-performing," in terms of the number of people they attract. It can inform planners about where to add amenities like parks and restaurants, or how much public transportation is needed for new urban developments.

The law of visitation joins a growing body of research in the science of cities, which SFI researchers and their collaborators have pioneered since 2007, when they first uncovered universal laws governing growth, innovation, and the pace of life in cities.

"All of the problems that we face, especially climate change are generated in cities because that's where the people are," West says. "So understanding cities, and how people move within them, plays into fundamental questions about the future of life on this planet."

INFORMATION:

* Co-authors are Markus Schläpfer (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Santa Fe Institute, Singapore-ETH Centre, ETH Zurich, Singapore), Lei Dong (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Peking University) Kevin O'Keeffe (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Paolo Santi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, CNR) Michael Szell (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, IT University of Copenhagen, ISI Foundation), Hadrien Salat (Singapore-ETH Centre, ETH Zurich, Singapore, Orange Labs), Samuel Anklesaria (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Mohammad Vazifeh (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Carlo Ratti (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and Geoffrey West (Santa Fe Institute).

What The Study Did: This study included data from more than 11,000 emergency medical services (EMS) agencies in 49 states to describe racial/ethnic, social and geographic changes in EMS-observed overdose-associated cardiac arrests during the COVID-19 pandemic through 2020 in the United States.

Authors: Joseph Friedman, M.P.H., of the University of California, Los Angeles, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0967)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

What The Study Did: Researchers conducted a review of studies examining the frequency and variety of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 infection.

Authors: Steven N. Goodman, M.D., M.H.S., Ph.D., of Stanford University in Stanford, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11417)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

What explains how often people travel to a particular place? Your intuition might suggest that distance is a key factor, but empirical evidence can help urban studies researchers answer the question more definitively.

A new paper by an MIT team, drawing on global data, finds that people visit places more frequently when they have to travel shorter distances to get there.

"What we have found is that there is a very clear inverse relationship between how far you go and how frequently you go there," says Paolo Santi, a research scientist at the Senseable City Lab at MIT and a co-author of the new paper. "You only seldom go to faraway places, and usually you tend to visit places close to you more often. It tells us how we organize our lives."

By examining cellphone data ...

What The Study Did: Researchers analyzed each state's department of health website for accessibility and usability challenges. Findings suggest state health department COVID-19 vaccine website accessibility and usability challenges create frustration, may promote health disparities and contribute to overall ineffective and inequitable distribution.

Authors: Raj M. Ratwani, Ph.D., of the Medstar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare in Washington, D.C., is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14861)

Editor's ...

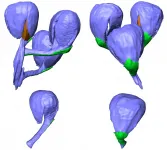

Seeing, hearing, thinking, daydreaming -- doing anything at all, in fact -- activates neurons in the brain. But for people predisposed to developing brain tumors, the ordinary buzzing of their brains could be a problem. A study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Stanford University School of Medicine shows that the normal day-to-day activity of neurons can drive the formation and growth of brain tumors.

The researchers studied mice genetically prone to developing tumors of their optic nerves, the bundle of neurons that carries ...

What The Study Did: Researchers quantified the added burden of fatal opioid overdoses occurring in Ontario, Canada, during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Tara Gomes, Ph.D., of the Keenan Research Centre of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12865)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding support disclosures. ...

What The Study Did: Researchers compared reporting practices for race, sex and socioeconomic status in randomized clinical trials published in general medical journals in 2015 with those published in 2019.

Authors: Asad Siddiqui, M.D., of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11516)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news ...

Flowering plants (angiosperms) dominate most terrestrial ecosystems, providing the bulk of human food. However, their origin has been a mystery since the earliest days of evolutionary thought.

Angiosperm flowers are hugely diverse. The key to clarifying the origin of flowers and how angiosperms might be related to other kinds of plants is understanding the evolution of the parts of the flower, especially angiosperm seeds and the fruits in which the seeds develop.

Fossil seed-bearing structures preserved in a newly discovered Early Cretaceous silicified peat in Inner Mongolia, China, provide a partial answer to the origin of flowering plants, according to a study led by Prof. SHI Gongle from the Nanjing ...

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 26, 2021) - Using novel imaging methods for studying brain metabolism, University of Kentucky researchers have identified the reservoir for a necessary sugar in the brain. Glycogen serves as a storage depot for the sugar glucose. The laboratories of Ramon Sun, Ph.D., assistant professor of neuroscience, Markey Cancer Center at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, and Matthew Gentry, Ph.D., professor of molecular and cellular biochemistry and director of the Lafora Epilepsy Cure Initiative at the University of Kentucky College ...

Berkeley -- The lifestyle of the horned passalus beetle, commonly known as the bessbug or betsy beetle, might seem downright disgusting to the average human: Not only does this shiny black beetle eat its own poop, known as frass, but it uses its feces to line the walls of its living space and to help build protective chambers around its developing young.

Gross as it may seem, a new study suggests that this beetle's frass habits are actually part of a clever strategy for protecting the insect's health -- and could help inform human medicine, too.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have discovered that the frass of the horned passalus beetle is teeming with antibiotic and antifungal chemicals similar to the ones that humans use to ward off bacterial and ...