INFORMATION:

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=OqI8eKCbMBY&feature=youtu.be

This work was funded by NIH grants NS106789 to K.E.S., NS040538 to C.L.S., NS070711 to C.L.S., NS108278 to C.L.S., NS104200 to G.D., NS0655926 to T.J.P., and 1S10OD021562-01 to the Northwest Metabolomics Research Center, startup funds to J.D.M., and the Research and Education Initiative Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Author contributions: K.E.S. planned, performed, and analyzed behavioral and electrophysiology experiments as well as wrote and edited the manuscript. F.M. planned, performed, and analyzed behavioral and electrophysiology experiments and edited the manuscript. S.I.S. planned, performed, and analyzed RNAscope experiments as well as wrote and edited the manuscript. L.J.L. planned, performed, and analyzed in vitro experiments; generated the TRPC5 stable cell lines; and edited the manuscript. A.R.M. planned, performed, and analyzed behavioral experiments and edited the manuscript. Z.R.P. planned, performed, and analyzed in vitro experiments and edited the manuscript. A.N.B. performed behavioral experiments and edited the manuscript. C.M.M. performed behavioral experiments and edited the manuscript. G.D. assisted in experimental planning and manuscript editing. T.J.P. assisted in experimental planning and manuscript editing. J.D.M. planned, performed, and analyzed in vitro experiments and edited the manuscript. C.L.S. assisted in experimental planning and in writing and editing the manuscript and provided the majority of NIH funding for the project.

About the Medical College of Wisconsin

With a history dating back to 1893, the Medical College of Wisconsin is dedicated to leadership and excellence in education, patient care, research, and community engagement. More than 1,400 students are enrolled in MCW's medical school and graduate school programs in Milwaukee, Green Bay and Central Wisconsin. MCW's School of Pharmacy opened in 2017. A major national research center, MCW is the largest research institution in the Milwaukee metro area and second largest in Wisconsin. In the last ten years, faculty received more than $1.5 billion in external support for research, teaching, training, and related purposes. This total includes highly competitive research and training awards from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Annually, MCW faculty direct or collaborate on more than 3,100 research studies, including clinical trials. Additionally, more than 1,600 physicians provide care in virtually every specialty of medicine for more than 2.8 million patients annually.

Identifying new, non-opioid based target for treating chronic pain

A non-opioid based target has been found to alleviate chronic touch pain and spontaneous pain in mice

2021-05-26

(Press-News.org) Milwaukee, May 26, 2021 - A non-opioid based target has been found to alleviate chronic touch pain and spontaneous pain in mice. Researchers at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) discovered that blocking transient receptor potential canonical 5 (TRPC5) activity reversed touch pain in mouse models of sickle cell disease, migraine, chemotherapy-related pain, and surgical pain.

TRPC5 is a protein that is expressed in both mouse and human neurons that send pain signals to the spinal cord. The findings were published in Science Translational Medicine. The senior and co-first authors of the manuscript, respectively, are MCW researchers Cheryl L. Stucky, PhD, professor, and Katelyn Sadler, PhD, postdoctoral fellow and former MCW postdoctoral fellow Francie Moehring, PhD, all of the Department of Cell Biology, Neurobiology and Anatomy (CBNA) at MCW. John McCorvy, assistant professor of CBNA, as well as graduate students and staff from the Stucky and McCorvy labs were also involved. Learn more about the research and the researchers here.

The MCW research team administered drugs that block TRPC5 activity to mice that had sickle cell disease, migraine, chemotherapy-related pain, or surgical pain, and found the drugs reversed touch pain in all of the models. Because each model differs in terms of how long the accompanying pain lasts and how the tissue is injured, researchers wanted to identify a convergent factor that could be driving pain (in a TRPC5-dependent fashion) in each model. Using lipid mass spectroscopy, the team identified lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) as a lipid that is elevated specifically at the site of injury in all of these pain models.

When TRPC5 inhibitors were tried in a mouse model of nerve damage, the drugs had no effect on pain. When LPC levels in the model were examined, they were unchanged compared to non-injured animals. The researchers believe that selective increases of the lipid drive pain by activating or sensitizing TRPC5. The McCorvy Lab expressed the mouse or human forms of TRPC5 in non-native cells, and using high-throughput screening approaches, determined that TRPC5 can be activated by specific doses of LPC. The Stucky Lab followed up on this finding, and injected LPC into mice; animals injected with this lipid develop touch pain and spontaneous pain.

To determine where TRPC5 inhibitors are exerting an analgesic effect, the researchers used the RNAscope technique to measure TRPC5 expression in the sensory neurons that convey pain signals to the spinal cord. Low levels of TRPC5 were found in mouse sensory neurons, and high levels of TRPC5 in human sensory neurons. LPC was applied to mouse sensory neurons and, using electrophysiology, the team found that incubation with this lipid increased the mechanical sensitivity of these cells. When TRPC5 inhibitors were applied to sensory neurons removed from mice with sickle cell disease and migraine, the mechanical sensitivity of these cells decreased.

"There are two TRPC5 inhibitors currently in clinical trials for kidney disease and depression," said Dr. Sadler. "Pending successful completion of Phase 1 safety tests, these drugs could potentially be fast tracked for use in chronic pain patients."

Of prescribing TRPC5 inhibitors broadly across all pain patient populations, Sadler said, "our identification of the relationship between LPC and TRPC5 could allow for the tailored application of TRPC5 drugs in types of pain that are associated with elevations of this lipid. In other words, LPC could be a biomarker for types of chronic pain that could be treated with a TRPC5 inhibitor."

"What I'm most excited about is that we found TRPC5 is highly expressed in human sensory neurons, and LPC has been shown to be elevated in patients with fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis in other studies, said Dr. Stucky. This means that TRPC5 could be a new, non-opioid target for alleviating pain in chronic inflammatory pain conditions that affect so many patients worldwide. Furthermore, our finding that TRPC5 had no effect on non-painful touch means that people can pick up their coffee cup, walk, dress themselves and caress their grandchild without losing tactile perception."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

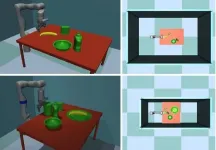

The path to more human-like robot object manipulation skills

2021-05-26

What if a robot could organize your closet or chop your vegetables? A sous chef in every home could someday be a reality.

Still, while advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning have made better robotics possible, there is still quite a wide gap between what humans and robots can do. Closing that gap will require overcoming a number of obstacles in robot manipulation, or the ability of robots to manipulate environments and adapt to changing stimuli.

Ph.D. candidate Jinda Cui and Jeff Trinkle, Professor and Chair of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering ...

Ultra-low doses of inhaled nanobodies effective against COVID-19 in hamsters

2021-05-26

PITTSBURGH, May 26, 2021 - In a paper published today in Science Advances, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine showed that inhalable nanobodies targeting the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can prevent and treat severe COVID-19 in hamsters. This is the first time the nanobodies--which are similar to monoclonal antibodies but smaller in size, more stable and cheaper to produce--were tested for inhalation treatment against coronavirus infections in a pre-clinical model.

The scientists showed that low doses of an aerosolized nanobody named Pittsburgh inhalable Nanobody-21 (PiN-21) protected hamsters from the dramatic weight loss ...

An inhalable nanobody-based treatment prevented and treated SARS-CoV-2 infections in hamsters

2021-05-26

An inhalable nanobody-based treatment may effectively prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infections when administered at ultra-low doses, according to a new study in Syrian hamsters. This novel therapy, Pittsburgh inhalable Nanobody 21 (PiN-21), could provide an affordable, needle-free alternative to monoclonal antibodies for treating early infections. Sham Nambulli and colleagues recently developed PiN-21, which uses single-domain antibody fragments that are cheaper to produce than monoclonal antibodies. However, until this study, the efficacy of PiN-21 had not been reported in living organisms. To advance the development of this treatment, Nambulli et al. administered a 0.6 milligram per kilogram ...

Salmon virus originally from the Atlantic, spread to wild Pacific salmon from farms: Study

2021-05-26

Piscine orthoreovirus (PRV) - which is associated with kidney and liver damage in Chinook salmon - is continually being transmitted between open-net salmon farms and wild juvenile Chinook salmon in British Columbia waters, according to a new genomics analysis published today in Science Advances.

The collaborative study from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the Strategic Salmon Health Initiative (SSHI) -- a partnership between Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Genome BC and the Pacific Salmon Foundation -- traces the origins of PRV to Atlantic salmon farms in Norway and finds that the virus is now almost ubiquitous in salmon farms in B.C.

It also shows that wild Chinook salmon are more likely to be infected with ...

Targeting plasmacytoid dendritic cells can reduce cutaneous lupus symptoms

2021-05-26

Jodi Karnell and colleagues have developed a monoclonal antibody, VIB7734, that reduces symptom severity in people with cutaneous lupus by targeting and depleting plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in blood and skin. In two phase I clinical trials involving a total of 67 people with autoimmune diseases such as lupus, treatment with VIB7734 was as safe as a placebo and significantly reduced pDC frequencies, the researchers found. The antibody also reduced the activity of a group of key immune proteins called type 1 interferons in skin. Both pDCs and type 1 interferons are suspected ...

Good bacteria can temper chemotherapy side effects

2021-05-26

In the human gut, good bacteria make great neighbors.

A new Northwestern University study found that specific types of gut bacteria can protect other good bacteria from cancer treatments -- mitigating harmful, drug-induced changes to the gut microbiome. By metabolizing chemotherapy drugs, the protective bacteria could temper short- and long-term side effects of treatment.

Eventually, the research could potentially lead to new dietary supplements, probiotics or engineered therapeutics to help boost cancer patients' gut health. Because chemotherapy-related microbiome changes in children are ...

Study finds ongoing evolution in Tasmanian Devils' response to transmissible cancer

2021-05-26

MOSCOW, Idaho -- May 26, 2021 -- University of Idaho researchers partnered with other scientists from the United States and Australia to study the evolution of Tasmanian devils in response to a unique transmissible cancer.

The team found that historic and ongoing evolution are widespread across the devils' genome, but there is little overlap of genes between those two timescales. These findings, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggest that if transmissible cancers occurred historically in devils, they imposed natural selection on different sets of genes.

Tasmanian devils suffer from a transmissible cancer called devil facial tumor disease (DFTD). Unlike typical cancers, tumor cells from transmissible cancers are directly transferred from one individual ...

Adult roles build skills for children of Latinx immigrants

2021-05-26

Children of Latinx immigrants who take on adult responsibilities exhibit higher levels of political activity compared with those who do not, according to University of Georgia researcher Roberto Carlos.

Immigrant communities often display low levels of political engagement, but a new study by Carlos indicates that when children of Latinx immigrants take on adult roles because of parents' long work hours, immigrant status or language deficiencies, they develop noncognitive skills associated with higher rates of political participation.

"There is thriving in spaces that we wouldn't necessarily expect because of the hardship related ...

No good decisions without good data: Climate, policymaking, the critical role of science

2021-05-26

"If you can't measure it, you can't improve it". This concept is also true within the context of climate policy, where the achievement of the objectives of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is dependent on the ability of the international community to accurately measure greenhouse gas (GHG) emission trends and, consequently, to alter these trends.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission inventories represent the link between national and international political actions on climate change, and climate and environmental sciences. Research communities and inventory agencies have approached the problem of climate ...

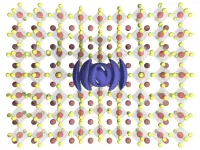

Study of promising photovoltaic material leads to discovery of a new state of matter

2021-05-26

Researchers at McGill University have gained new insight into the workings of perovskites, a semiconductor material that shows great promise for making high-efficiency, low-cost solar cells and a range of other optical and electronic devices.

Perovskites have drawn attention over the past decade because of their ability to act as semiconductors even when there are defects in the material's crystal structure. This makes perovskites special because getting most other semiconductors to work well requires stringent and costly manufacturing techniques to produce crystals that are as defect-free ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Identifying new, non-opioid based target for treating chronic painA non-opioid based target has been found to alleviate chronic touch pain and spontaneous pain in mice