INFORMATION:

About Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. WHOI's pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering--one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide--both above and below the waves--pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu

Media Contact:

Suzanne Pelisson

Associate Director, Public Relations

SPelisson@WHOI.edu

Authors: Fatma Gomaa1,2*, Daniel R. Utter2, Christopher Powers3, David J. Beaudoin1, Virginia P. Edgcomb1, Helena L. Filipsson4, Colleen M. Hansel5, Scott D. Wankel5, Ying Zhang3, and Joan M. Bernhard1*

Affiliations:

1Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA

2Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

3Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, College of the Environment and Life Sciences, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA

4Lund University, Department of Geology, Lund, Sweden.

5Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA

*Corresponding author

Some forams could thrive with climate change, metabolism study finds

2021-05-27

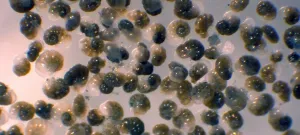

(Press-News.org) Woods Hole, Mass. (May 27, 2021) - With the expansion of oxygen-depleted waters in the oceans due to climate change, some species of foraminifera (forams, a type of protist or single-celled eukaryote) that thrive in those conditions could be big winners, biologically speaking.

A new paper that examines two foram species found that they demonstrated great metabolic versatility to flourish in hypoxic and anoxic sediments where there is little or no dissolved oxygen, inferring that the forams' contribution to the marine ecosystem will increase with the expansion of oxygen-depleted habitats.

In addition, the paper found that the multiple metabolic strategies that these forams exhibit to adapt to low and no oxygen conditions are changing the classical view about the evolution and diversity of eukaryotes. That classical view hypothesizes that the rise of oxygen in Earth's system led to the acquisition of oxygen-respiring mitochondria, the part of a cell that generates most of the chemical energy that powers a cell's biochemical reactions. The forams in the study represent "typical" mitochondrial-bearing eukaryotes. However, these two forams respire nitrate and produce energy in the absence of oxygen, with one colonizing an anoxic environment, often with high levels of hydrogen sulfide, a chemical compound typically toxic to eukaryotes.

"Benthic foraminifera represent truly successful microbial eukaryotes with diverse and sophisticated metabolic adaptive strategies" that scientists are just beginning to discover, the authors noted in the paper, Multiple integrated metabolic strategies allow foraminiferal protists to thrive in anoxic marine sediments appearing in Science Advances.

This is important because scientists have studied forams extensively for interpreting past oceanographic and climate conditions. Scientists largely have assumed that forams evolved after oxygen was on the planet and likely require oxygen to survive. However, finding that forams can perform the processes described "throws a whole new wrench in interpretations of past environmental conditions on Earth, driven by the foram fossil record," said co-author and project leader Joan Bernhard, senior scientist in the Geology and Geophysics Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

Bernhard said that over the past several decades she has worked to establish that forams can live where there is little or no oxygen. "We never knew exactly why forams can live where there isn't any oxygen until molecular methods got good enough that we could really start to ask some of these questions. This is our first paper that's coming out with some of these insights," she said. Bernhard added that with thousands of foram species living today, and with hundreds of thousands extinct, it is likely that this is "the tip of the iceberg" in terms of possibly discovering other metabolic strategies invoked by these forams.

Specific insights from the paper pertain to two highly successful benthic foraminiferal species that inhabit hypoxic or anoxic sediments in the Santa Barbara Basin, a sort of natural laboratory off the coast of California for studying the impact of oxygen depletion in the ocean.

Through gene expression analysis of the two species--Nonionella stella and Bolivina argentea--scientists found different successful metabolic adaptations that allowed the forams to succeed in oxygen-depleted marine sediments and identified candidate genes involved in anaerobic respiration and energy metabolism.

The N. stella is a sort of kleptomaniac, utilizing a technique to steal chloroplasts--the structure in a cell where photosynthesis occurs--from a particular diatom genus. What makes this particularly interesting is that N. stella lives well below what is considered to be the zone where photosynthesis can happen. The authors noted that there has been discussion in the literature questioning the functionality of these kleptoplasts in the Santa Barbara Basin N. stella but the new results show that these kleptoplasts are firmly functional, although exact metabolic details remain elusive.

In addition, the scientists found that the two foram species in the study use different metabolic pathways to incorporate ammonium into organic nitrogen in the form of glutamate, a metabolic strategy that was not previously known to be performed by these organisms.

"The metabolic variety suggests that at least some species of this diverse protistan group will withstand severe deoxygenation and likely play major roles in oceans affected by climate change," the authors wrote.

The study "gives the scientific community a new direction for research," said lead author Fatma Gomaa, who, at the time of the study, was a postdoctoral investigator at the Geology and Geophysics Department at WHOI. "We are now starting to learn that there are microeukaryotes living in habitats similar to those in Earth's early history that are performing very interesting biological functions. Learning about these forams is very intriguing and will shed light on how early eukaryotes evolved."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Physical activity levels and well-being sink worldwide during coronavirus restrictions

2021-05-27

Twenty scientists from 14 countries warn of a hidden "pandemic within the pandemic" in two current publications. On the one hand, physical activity levels have gone down significantly, on the other hand, psychological well-being has suffered. "Governments and those responsible for health systems should take our findings seriously," emphasizes the author team, headed by Dr Jan Wilke from the Institute for Sport Sciences at Goethe University Frankfurt.

About 15,000 people in participating countries answered standardised questionaires as part of an international survey. In April/May 2020, they reported physical activity levels (13,500 participants) as well as their mental and physical well-being (15,000 participants) ...

How New Zealand's cheeky kea and kākā will fare with climate change

2021-05-27

With global warming decreasing the size of New Zealand's alpine zone, a University of Otago study found out what this means for our altitude-loving kea.

The study, published in Molecular Ecology, analysed whole genome DNA data of the kea and, for the first time, its forest-adapted sister species, the kākā, to identify genomic differences which cause their habitat specialisations.

The researchers found the kea is not an alpine specialist, but rather one that adapted to using such an open habitat because it was least disturbed by human activity.

Co-author Associate Professor Michael Knapp, of the Department of Anatomy, says that is not likely to surprise people ...

New methods proposed to characterize polymer lamellar crystals

2021-05-27

Different from small molecules, polymer will fold into lamellar crystals during crystallization and further assemble into lamellar stacks.

Synchrotron Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) is an important tool to characterize such nanoscale structure and understand polymer crystallization. However, its scattering mechanism in semi-crystalline polymers is not completely elucidated yet.

Recently, a research group led by Prof. TIAN Xingyou from Institute of Solid State Physics, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), proposed a complete set of new methods to characterize polymer lamellar crystals ...

Novel way by NUS scientists to predict chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer patients

2021-05-27

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most common lethal gynaecological cancer. Ovarian cancer is usually treated with platinum-based chemotherapy; however, a significant number of patients are resistant to such treatments and relapse soon afterwards. To improve their survival, there is a need to first identify which patients may be platinum-resistant, so that newer treatments may be administered early.

Now, researchers from the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore (CSI Singapore) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), have discovered a way to predict which patients are resistant to platinum chemotherapy. The study, co-led by CSI Singapore Principal ...

'Shortcuts' to increase female enrollment in economics may backfire, OSU study cautions

2021-05-27

Current best practices for encouraging more female students to pursue degrees in economics may actually have the opposite effect and worsen gender disparities in the field, a recent study from Oregon State University found.

The study examined whether mass emails telling introductory economic students about promising career and earning opportunities helped increase female participation in higher-level economics courses. But instead, these emails appealed more to male students, increasing male enrollment and widening the existing gender gap. There was no change in the probability of female students majoring in economics.

Researchers say this demonstrates a need for more personalized, deliberate interventions.

"There ...

Ionophobic electrode boosts energy storage performance

2021-05-27

Using renewable energy to replace fossil energy is now considered the best solution for greenhouse gas emission and air pollution problems. As a result, the demand for new and better energy storage technology is strong.

As part of the effort to improve this technology, a group led by Prof. ZHANG Suojiang from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently found that ionophobic electrodes can boost energy storage performance.

Their study was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A on May 8.

Electric Double-Layer Capacitors (EDLCs) with ionic liquids (ILs)--as a new type of energy storage device--can fill the gap between the power density of batteries and the ...

Fish adapt to ocean acidification by modifying gene expression

2021-05-27

Human-driven global change is challenging the scientific community to understand how marine species might adapt to predicted environmental conditions in the near-future (e.g. hypoxia, ocean warming, and ocean acidification). The effects of the uptake of anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 by oceans affects (i.e. ocean acidification) propagate across the biological hierarchy, from changes in the building blocks of life at nano-scales to organism, physiology and behaviour through ecosystem processes and their properties.

To survive in a reduced pH environment, marine organisms have to adjust their physiology which, at the molecular level, is achieved by modifying the expression ...

Quantification of the internal OH- effects in upconversion nanocrystals

2021-05-27

The great application prospect in biology, medicine, optogenetics, photovoltaics and sustainability has enabled lanthanide ions-doped upconversion nanoparticles to attract widespread attention which derives mainly from their superior anti-Stokes spectroscopic property. However, the relatively low upconversion efficiency remains a major bottleneck on their way of actual applications. Internal OH- impurity is known as one of the main detrimental factors affecting the upconversion efficiency of nanomaterials. Different from surface/ligand related emission quenching which can be effectively diminished by, e.g., core/shell structure, internal OH- is easy to be introduced during synthesis but difficult to be quantified and controlled.

In a new paper published in Light Science ...

Low on antibodies, blood cancer patients can fight off COVID-19 with T cells

2021-05-27

PHILADELPHIA--Antibodies aren't the only immune cells needed to fight off COVID-19 -- T cells are equally important and can step up to do the job when antibodies are depleted, suggests a new Penn Medicine study of blood cancer patients with COVID-19 published in Nature Medicine. The researchers found that blood cancer patients with COVID-19 who had higher CD8 T cells, many of whom had depleted antibodies from cancer treatments, were more than three times likelier to survive than patients with lower levels of CD8 T cells.

"It's clear T cells are critical in terms of the early infection and to help control the virus, but we also showed that they can compensate for B cell and antibody responses, which blood cancer patients are likely missing because of the drugs," said co-senior author Alexander ...

Fungus fights mites that harm honey bees

2021-05-27

PULLMAN, Wash. -- A new fungus strain could provide a chemical-free method for eradicating mites that kill honey bees, according to a study published this month in Scientific Reports.

A team led by Washington State University entomologists bred a strain of Metarhizium, a common fungus found in soils around the world, to work as a control agent against varroa mites. Unlike other strains of Metarhizium, the one created by the WSU research team can survive in the warm environments common in honey bee hives, which typically have a temperature of around 35 Celsius (or 95 F).

"We've known that metarhizium could kill mites, but it was expensive and didn't last long because the fungi died in the hive heat," said Steve Sheppard, professor in WSU's Department of Entomology and corresponding ...