(Press-News.org) Many seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere are struggling to breed -- and in the Southern Hemisphere, they may not be far behind. These are the conclusions of a study, published May 28 in Science, analyzing more than 50 years of breeding records for 67 seabird species worldwide.

The international team of scientists -- led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in California -- discovered that reproductive success decreased in the past half century for fish-eating seabirds north of the equator. The Northern Hemisphere has suffered greater impacts from human-caused climate change and other human activities, like overfishing.

Seabirds include albatrosses, puffins, murres, penguins and other birds. Whether they soar or swim, all seabirds are adapted to feed in and live near ocean waters. Many scientists view seabirds as sentinels of habitat health because their lives and well-being depend on sound conditions both on land and at sea, said co-author P. Dee Boersma, a University of Washington professor of biology and director of the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels.

"Seabirds travel long distances -- some going from one hemisphere to the other -- chasing their food in the ocean," said Boersma. "This makes them very sensitive to changes in things like ocean productivity, often over a large area."

In addition, seabirds congregate at particular sites along coasts to breed and rear their young, which makes them vulnerable to changing shore and surface conditions and restricts how far they can travel for food while still successfully raising their chicks, Boersma added.

Seabird diets played a major role in their ability to rear chicks. In the north, fish-eating seabirds saw a significant decline in reproductive success over the study period. In addition, surface-feeding birds in both hemispheres were more prone to reproductive failure, regardless of whether they ate fish or smaller plankton, like krill. Deep-diving birds, like puffins, fared best in terms of reproductive success.

The team believes changing environmental conditions are to blame. Seabirds must travel far for food, and eat a lot -- murres, for example, must consume half their body weight in fish daily. Nearly 1 million murres starved to death and breeding colonies crashed in 2015-2016 due to a long-term marine heat wave that disrupted food webs in the northeast Pacific [1]. Climate change is causing more frequent and more extreme events like those heat waves, and seabirds out in the ocean face other threats as well.

"They have to compete with us for food. They can get caught in our fishing nets. They eat our plastic, which they think is food," said Boersma. "All of these factors can kill off large numbers of long-lived seabirds."

These changes have implications beyond seabirds.

"What's also at stake is the health of fish populations such as salmon and cod, as well as marine mammals and large invertebrates, such as squid, that are eating the same small forage fish and plankton that seabirds eat," said Sydeman. "When seabirds aren't doing well, this is a red flag that something bigger is happening below the ocean's surface which is concerning because we depend on healthy oceans for quality of life."

The team found high variability in reproductive success among species, showing that additional research is needed to understand all of the factors that shape feeding and breeding for these species.

Boersma's research on South American penguins illustrates just how much local conditions at sea and on land shape reproductive success. For the study, she contributed more than 35 years of data on breeding success at Punta Tombo, a site with one of the largest breeding colonies for Magellanic penguins in southern Argentina. Over nearly four decades, Punta Tombo has changed rapidly.

"Today the breeding population at Punta Tombo is about half of what it was in the early 1980s," said Boersma.

During the breeding season each summer, Magellanic parents must frequently return to the water to catch fish for their chicks. Changing ocean conditions mean that adults must travel farther from Punta Tombo to find food, increasing the risk of chick starvation, Boersma said. Conditions on land, such as frequent storms, can also destroy nests and kill chicks, she added.

Conditions far out at sea, where Magellanic penguins spend months feeding each winter after the breeding season, are also shaping Punta Tombo. The proportion of male Magellanic penguins at that site has risen over the years, and as a result many males cannot find a mate. Boersma and her team have found that harsh oceanographic conditions punish females more than males [2]. In addition, juvenile females are more likely to die at sea while they're trying to find food [3].

Southern seabirds fared better overall, the new study found. But over time, southern conditions may catch up to the already-poor conditions in the north, Boersma said.

These findings can be a call to protect sentinels like seabirds, as well as other species impacted by rising ecosystem stress, the researchers said. This requires protecting seabirds across all of their habitats, on land and at sea.

On land, seabirds can attract a lot of attention from people, especially during breeding seasons. But this does not necessarily translate to greater protection for breeding colonies. For example, Boersma and two colleagues recently surveyed almost 300 breeding colonies for penguins around the world that are open to tourists [4]. Fewer than half had management plans to protect the environment, parents and chicks from curious human visitors.

At sea, establishing marine preserves would protect seabird feeding waters from overfishing, vessel traffic, pollution and energy extraction -- giving these birds a much-needed boost in the face of climate change.

"By knowing what is important to a species for success, we can make the world a better place for its survival," said Boersma.

INFORMATION:

For more information, contact Boersma at boersma@uw.edu and Sydeman at wsydeman@faralloninstitute.org.

Link to companion release from the U.K. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology and the Farallon Institute (EurekAlert registration required): https://www.eurekalert.org/emb_releases/2021-05/ucfe-ssa052421.php

References:

1. https://www.washington.edu/news/2020/01/15/the-blob-food-supply-squeeze-to-blame-for-largest-seabird-die-off/

2. https://www.washington.edu/news/2018/11/07/magellanic-penguins-oceanography/

3. https://www.washington.edu/news/2019/01/02/single-male-magellanic-penguins/

4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964569120303367

A new paper, published recently in PLOS Computational Biology by a team including UMass Amherst researchers, seeks to help scientists structure their lab-group meetings so that they are more inclusive, more productive and, ultimately, lead to better science.

The word "scientist" might conjure images of lab-coated researchers tending bubbling beakers or building supercomputers, but an enormous amount of scientific work takes place around a conference table during weekly group meetings. "There is plenty of good research showing that diversity and inclusion make the science itself better," says Kadambari Devarajan, one of the paper's co-lead authors and a graduate ...

The blood-brain barrier is impermeable to cholesterol, yet high blood cholesterol is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. However, the underlying mechanisms mediating this relationship are poorly understood. A study published in the open-access journal PLOS Medicine by Vijay Varma and colleagues at the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, in Baltimore, Maryland, suggests that disturbances in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids (called cholesterol catabolism) may play a role in the development of dementia.

Little ...

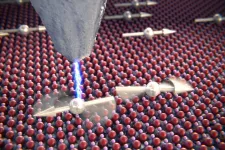

Quantum systems are considered extremely fragile. Even the smallest interactions with the environment can result in the loss of sensitive quantum effects. In the renowned journal Science, however, researchers from TU Delft, RWTH Aachen University and Forschungszentrum Jülich now present an experiment in which a quantum system consisting of two coupled atoms behaves surprisingly stable under electron bombardment. The experiment provide an indication that special quantum states might be realised in a quantum computer more easily than previously thought.

The so-called decoherence is one of the greatest enemies of the quantum physicist. Experts understand by this the decay of quantum states. This inevitably occurs when the system interacts with its environment. In ...

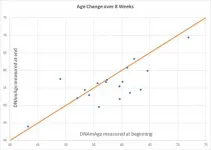

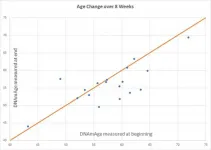

A groundbreaking clinical trial shows we can reduce biological age (as measured by the Horvath 2013 DNAmAge clock) by more than three years in only eight weeks with diet and lifestyle through balancing DNA methylation. A first-of-its-kind, peer-reviewed study provides scientific evidence that lifestyle and diet changes can deliver immediate and rapid reduction of our biological age. Since aging is the primary driver of chronic disease, this reduction has the power to help us live better, longer. The study, released on April 12, utilized a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted among 43 healthy adult males between the ages of 50-72. The 8-week treatment program included diet, sleep, exercise and relaxation ...

The bacterium, which they named Candidatus Phytoplasma dypsidis was found to cause a fatal wilt disease. This new discovery was reported in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.

In 2016, several ornamental palms within a conservatory in the Cairns Botanic Gardens, Queensland, died mysteriously. A sample was taken from one of the diseased plants and investigated by Dr Richard Davis and colleagues from the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, and state and local government. They compared the characteristics and genome of the bacterium identified as the cause of the disease and found the ...

Study Exploring Optimization of Duplex Velocity Criteria for Diagnosis of Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) Stenosis Published Online

Online first in Vascular Medicine, researchers from the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC) Vascular Testing division report findings of their multi-centered study of duplex ultrasound for diagnosis of internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis. 1

The study was developed in response to wide variability in the diagnostic criteria used to classify severity of ICA stenosis across vascular laboratories nationwide and following a survey of members of IAC-accredited ...

Aging published "Potential reversal of epigenetic age using a diet and lifestyle intervention: a pilot randomized clinical trial" which reported on a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted among 43 healthy adult males between the ages of 50-72. The 8-week treatment program included diet, sleep, exercise and relaxation guidance, and supplemental probiotics and phytonutrients. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis was conducted on saliva samples using the Illumina Methylation Epic Array and DNAmAge was calculated using the online Horvath DNAmAge clock (also published in Aging). The diet and lifestyle treatment was associated with a 3.23 years decrease in DNAmAge compared with controls. DNAmAge of those in the treatment group decreased by an average 1.96 ...

More than 500,000 people have died from COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean, demonstrating the health and economic inequalities throughout the region. A new article analyzes seven books* that discuss these inequalities, including questions of who gets health care and what interdependent roles societies, social movements, and governments play. To end inequality in the region, the author calls for a universal approach to health care.

The article, by a professor at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), appears in the June 2021 issue of Latin American Research Review, a journal published by the Latin American Studies Association.

"These books break new ground and contribute to our understanding of some of the most important health ...

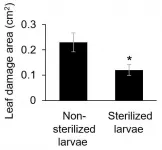

Although insect larvae may seem harmless to humans, they can be extremely dangerous to the plant species that many of them feed on, and some of those plant species are important as agricultural crops. Although plants cannot simply flee from danger like animals typically would, many have nonetheless evolved ingenious strategies to defend themselves from herbivores. Herbivorous insect larvae will commonly use their mouths to smear various digestive proteins onto plants that they want to eat, and when plants detect chemicals commonly found in these oral secretions, ...

AMES, Iowa - Materials engineers don't like to see line defects in functional materials.

The structural flaws along a one-dimensional line of atoms generally degrades performance of electrical materials. So, as a research paper published today by the journal Science reports, these linear defects, or dislocations, "are usually avoided at all costs."

But sometimes, a team of researchers from Europe, Iowa State University and the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory report in that paper, engineering those defects in some oxide crystals can actually increase electrical performance.

The research team - led by Jürgen Rödel and Jurij Koruza of the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany - found certain defects produce significant improvements in two key measurements ...