(Press-News.org) There is heightened public awareness that the world's oceans are under duress, with over-fishing and plastic pollution as some of the more tangible problems. Now, seabirds are calling attention to another problem and have delivered a warning message.

Serving as translators of the birds' message, an international team of 40 scientists led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in northern California published findings on May 28 in the journal Science that some seabirds are struggling to raise young where the globe is most rapidly warming - in the northern hemisphere.

Using over 50 years of data from 67 seabird species across the globe, the team found that the breeding success of fish-eating seabirds in the north has trended downwards through time, meaning that they are producing fewer offspring each year.

"Seabirds can handle short-term declines in breeding success, but when breeding success becomes chronically poor - that's not good," says Sydeman. He explains that because seabirds rely on food like small fish and plankton (e.g., krill), long-term declines in their breeding success indicates that food resources aren't holding up in ecosystems where the rate of ocean warming and other human impacts are highest.

Marine ecologists have often likened seabirds to "canaries in the coalmine" because of their sensitivity to environmental disturbances. This sensitivity is due to the challenge of raising young at dedicated sites on land (or on stationary ice) while their ocean-based food is constantly on the move.

Furthermore, seabirds need to consume roughly half of their body weight in this food daily, making them susceptible to reduced food availability due to climate or other factors.

Coauthor Marisol García-Reyes, an oceanographer at the Farallon Institute, explains that as climate warming alters ocean habitats, the locations of temperature zones in which various seabird food thrives can shift farther away from seabird breeding sites -- and that's when the birds suffer.

Indeed, less than a decade ago there was an estimated 1 million murres (a common seabird pictured above) that starved to death in the North Pacific due to an unprecedented marine heatwave that disrupted the food web.

According to Sydeman, while marine heatwaves may produce dramatic mortality events such as the murre die-off in the Northeast Pacific, long-term degradation of our marine ecosystems is a more insidious problem.

Sydeman emphasizes that the implications of the study extend well beyond seabirds. "What's also at stake is the health of fish populations such as salmon and cod, as well as marine mammals and large invertebrates, such as squid, that are eating the same small forage fish and plankton that seabirds eat. When seabirds aren't doing well, this is a red flag that something bigger is happening below the ocean's surface which is concerning because we depend on healthy oceans for quality of life."

On a more hopeful note, Sydeman points to their study's results that seabirds in the north that forage on plankton have not suffered the same declines in breeding success as have those that feed on fish, and that breeding failures were less likely for birds that forage in deeper water. These patterns could signal resilience for some deeper-diving birds like puffins. Declining trends in seabird breeding success in the southern hemisphere have also not been so severe, but plankton-feeders show a declining trend.

Policies to alleviate climate change are obviously needed, a long-term solution brought forth in the paper. But the authors also suggest that in the north, where global warming may be worsened by additional human impacts like fishing, fisheries closures around breeding colonies during chick rearing periods will be needed to ease pressure.

In the south, where the rate of human-induced changes is picking up, creation of long-term Marine Protected Areas could prevent those birds from similar fates to their northern counterparts.

Sydeman and his team caution that there is a lot of variability in the data, and that more work is needed to understand why some species are doing better or worse than others. "We don't understand all of the mechanisms at play here, as marine ecosystems are so complex and we often can't observe key changes directly," says Sydeman.

The authors stress the critical importance of maintaining long-term seabird monitoring programs, some of which may be canceled due to changing governmental funding allocations.

To coauthor Brian Hoover, of Chapman University, California, the collaboration among scientists was perhaps the most meaningful outcome of their study. "Scientists from all over came together to contribute their efforts to the bigger picture and that enabled us to discover global ecological trends that wouldn't have been apparent from singular datasets - that's inspiring and shows what we can accomplish working together."

INFORMATION:

About Farallon Institute, California

Farallon Institute is a non-profit scientific organization dedicated to the understanding and preservation of healthy marine ecosystems. Its research is designed to provide the scientific basis for ecosystem-based management practices and policy reforms consistent with a productive marine world.

Farallon Institute emphasizes long-term, multi-species, multi-disciplinary research into the interdependent aspects of the marine environment, including the effects of natural and human based climate change, and the broad implications and influences of ocean currents, weather patterns, fishing practices and coastal development on marine food webs and ecosystem processes.

We are committed to an inclusive and equitable work environment, and strive to create diverse research teams to foster a marine scientific community that reflects the communities reliant upon the world's oceans.

In a study that uniquely evaluates marine ecosystem responses to a changing climate by hemisphere, researchers report that the fish-eating, surface-foraging bird species of the Northern Hemisphere suffered greater breeding productivity stresses over the last half-century than their Southern Hemisphere counterparts. The findings suggest the need for ocean management at hemispheric scales and underscore the importance of long-term seabird monitoring programs - some of which are already under threat - by illustrating the critical role that seabirds play as sentinels of global marine change. To date, global understanding of ocean change has not explicitly considered differences, ...

Australian researchers recently reported a sharp decline in the abundance of coral along the Great Barrier Reef. Scientists are seeing similar declines in coral colonies throughout the world, including reefs off of Hawaii, the Florida Keys and in the Indo-Pacific region.

The widespread decline is fueled in part by climate-driven heat waves that are warming the world's oceans and leading to what's known as coral bleaching, the breakdown of the mutually beneficial relationship between corals and resident algae.

But other factors are contributing to the decline ...

HOUSTON - (May 27, 2021) - One hundred fifty years ago, Dmitri Mendeleev created the periodic table, a system for classifying atoms based on the properties of their nuclei. This week, a team of biologists studying the tree of life has unveiled a new classification system for cell nuclei and discovered a method for transmuting one type of cell nucleus into another.

The study, which appears this week in the journal Science, emerged from several once-separate efforts. One of these centered on the DNA Zoo, an international consortium spanning dozens of institutions including Baylor College of ...

Many seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere are struggling to breed -- and in the Southern Hemisphere, they may not be far behind. These are the conclusions of a study, published May 28 in Science, analyzing more than 50 years of breeding records for 67 seabird species worldwide.

The international team of scientists -- led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in California -- discovered that reproductive success decreased in the past half century for fish-eating seabirds north of the equator. The Northern Hemisphere has suffered greater impacts from human-caused climate change and other human activities, like overfishing.

Seabirds include albatrosses, puffins, murres, penguins and other birds. Whether they ...

A new paper, published recently in PLOS Computational Biology by a team including UMass Amherst researchers, seeks to help scientists structure their lab-group meetings so that they are more inclusive, more productive and, ultimately, lead to better science.

The word "scientist" might conjure images of lab-coated researchers tending bubbling beakers or building supercomputers, but an enormous amount of scientific work takes place around a conference table during weekly group meetings. "There is plenty of good research showing that diversity and inclusion make the science itself better," says Kadambari Devarajan, one of the paper's co-lead authors and a graduate ...

The blood-brain barrier is impermeable to cholesterol, yet high blood cholesterol is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. However, the underlying mechanisms mediating this relationship are poorly understood. A study published in the open-access journal PLOS Medicine by Vijay Varma and colleagues at the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, in Baltimore, Maryland, suggests that disturbances in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids (called cholesterol catabolism) may play a role in the development of dementia.

Little ...

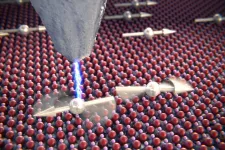

Quantum systems are considered extremely fragile. Even the smallest interactions with the environment can result in the loss of sensitive quantum effects. In the renowned journal Science, however, researchers from TU Delft, RWTH Aachen University and Forschungszentrum Jülich now present an experiment in which a quantum system consisting of two coupled atoms behaves surprisingly stable under electron bombardment. The experiment provide an indication that special quantum states might be realised in a quantum computer more easily than previously thought.

The so-called decoherence is one of the greatest enemies of the quantum physicist. Experts understand by this the decay of quantum states. This inevitably occurs when the system interacts with its environment. In ...

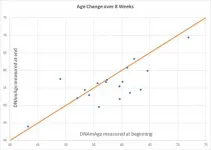

A groundbreaking clinical trial shows we can reduce biological age (as measured by the Horvath 2013 DNAmAge clock) by more than three years in only eight weeks with diet and lifestyle through balancing DNA methylation. A first-of-its-kind, peer-reviewed study provides scientific evidence that lifestyle and diet changes can deliver immediate and rapid reduction of our biological age. Since aging is the primary driver of chronic disease, this reduction has the power to help us live better, longer. The study, released on April 12, utilized a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted among 43 healthy adult males between the ages of 50-72. The 8-week treatment program included diet, sleep, exercise and relaxation ...

The bacterium, which they named Candidatus Phytoplasma dypsidis was found to cause a fatal wilt disease. This new discovery was reported in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.

In 2016, several ornamental palms within a conservatory in the Cairns Botanic Gardens, Queensland, died mysteriously. A sample was taken from one of the diseased plants and investigated by Dr Richard Davis and colleagues from the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, and state and local government. They compared the characteristics and genome of the bacterium identified as the cause of the disease and found the ...

Study Exploring Optimization of Duplex Velocity Criteria for Diagnosis of Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) Stenosis Published Online

Online first in Vascular Medicine, researchers from the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC) Vascular Testing division report findings of their multi-centered study of duplex ultrasound for diagnosis of internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis. 1

The study was developed in response to wide variability in the diagnostic criteria used to classify severity of ICA stenosis across vascular laboratories nationwide and following a survey of members of IAC-accredited ...