(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- By delivering small electrical pulses directly to the brain, deep brain stimulation (DBS) can ease tremors associated with Parkinson's disease or help relieve chronic pain. The technique works well for many patients, but researchers would like to make DBS devices that are a little smarter by adding the capability to sense activity in the brain and adapt stimulation accordingly.

Now, a new algorithm developed by Brown University bioengineers could be an important step toward such adaptive DBS. The algorithm removes a key hurdle that makes it difficult for DBS systems to sense brain signals while simultaneously delivering stimulation.

"We know that there are electrical signals in the brain associated with disease states, and we'd like to be able to record those signals and use them to adjust neuromodulation therapy automatically," said David Borton, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Brown and corresponding author of a study describing the algorithm. "The problem is that stimulation creates electrical artifacts that corrupt the signals we're trying to record. So we've developed a means of identifying and removing those artifacts, so all that's left is the signal of interest from the brain."

The research is published in the journal Cell Reports Methods. The work was co-led by Nicole Provenza, a Ph.D. candidate working in Borton's lab at Brown, and Evan Dastin-van Rijn, a Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota who worked on the project while he was an undergraduate at Brown advised by Borton and Matthew Harrison, an associate professor of applied mathematics. Borton's lab is affiliated the Brown's Carney Institute for Brain Science.

DBS systems typically consist of an electrode implanted in the brain that's connected to a pacemaker-like device implanted in the chest. Electrical pulses are delivered at a consistent frequency, which is set by a doctor. The stimulation frequency can be adjusted as disease states change, but this has to be done manually by a physician. If devices could sense biomarkers of disease and respond automatically, it could lead to more effective DBS therapy with potentially fewer side effects.

There are several factors that make it difficult to sense and stimulate at the same time, the researchers say. For one thing, the frequency signature of the stimulation artifact can sometimes overlap with that of the brain signal researchers want to detect. So merely cutting out swaths of frequency to eliminate artifacts might also remove important signals. To eliminate the artifact and leave other data intact, the exact waveform of the artifact needs to be identified, which presents another problem. Implanted brain sensors are generally designed to run on minimal power, so the rate at which sensors sample electrical signals makes for fairly low-resolution data. Accurately identifying the artifact waveform with such low-resolution data is a challenge.

To get around that problem, the researchers came up with a way to turn low-resolution data into a high-resolution picture of the waveform. Even though sensors don't collect high-resolution data, they do collect a lot of data over time. Using some clever mathematics, the Brown team found a way to cobble bits of data together into a high-resolution picture of the artifact waveform.

"We basically take an average of samples recorded at similar points along the artifact waveform," Dastin-van Rijn said. "That allows us to predict the contribution of the artifact in those kinds of samples, and then remove it."

In a series of laboratory experiments and computer simulations, the team showed that their algorithm outperforms other techniques in its ability to separate signal from artifact. The team also used the algorithm on previously collected data from humans and animal models to show that they could accurately identify artifacts and remove them.

"I think one big advantage to our method is that even when the signal of interest closely resembles the simulation artifact, our method can still tell the difference between the two," Provenza said. "So that way we're able to get rid of the artifact while leaving the signal intact."

Another advantage, the researchers say, is that the algorithm isn't computationally expensive. It could potentially run in real time on current DBS devices. That opens the door to real-time artifact-filtering, which would enable simultaneous recording and stimulation.

"That's the key to an adaptive system," Borton said. "Being able to get rid of the stimulation artifact while still recording important biomarkers is what will ultimately enable a closed-loop therapeutic system."

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors on the research were Jonathan Calvert, Ro'ee Gilron, Anusha Allawala, Radu Darie, Sohail Syed, Evan Matteson, Gregory Vogt, Michelle Avendano-Ortega, Ana Vasquez, Nithya Ramakrishnan, Denise Oswalt, Kelly Bijanki, Robert Wilt, Philip Starr, Sameer Sheth, Wayne Goodman and Matthew Harrison. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Brain Initiative (UH3NS100549, UH3NS103549, UH3NS100544), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (D15AP00112) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (T32NS100663-04).

A provisional patent for the technology has been filed (63 / 175,838).

Researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences have developed a robotic mechanism for mushroom picking and trimming and demonstrated its effectiveness for the automated harvesting of button mushrooms.

In a new study, the prototype, which is designed to be integrated with a machine vision system, showed that it is capable of both picking and trimming mushrooms growing in a shelf system.

The research is consequential, according to lead author Long He, assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering, because the mushroom industry has been facing labor shortages and rising labor costs. Mechanical or robotic picking can help alleviate those problems.

"The mushroom industry in Pennsylvania is producing about two-thirds of the mushrooms ...

Older adults with cognitive impairment are two to three times more likely to fall compared with those without cognitive impairment. What's more, the increasing use of pain medications for chronic pain by older adults adds to their falls risk. Risks associated with falls include minor bruising to more serious hip fractures, broken bones and even head injuries. With falls a leading cause of injury for people aged 65 and older, it is an important public health issue to study in order to allow these adults increased safety and independence as they age.

Although elevated risk of falls due to use of pain medication by older adults has been widely studied, less ...

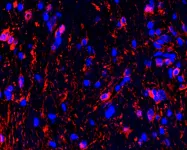

In a study of mice, researchers showed how the act of seeing light may trigger the formation of vision-harming tumors in young children who are born with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) cancer predisposition syndrome. The research team, funded by the National Institutes of Health, focused on tumors that grow within the optic nerve, which relays visual signals from the eyes to brain. They discovered that the neural activity which underlies these signals can both ignite and feed the tumors. Tumor growth was prevented or slowed by raising young mice in the dark or treating them with an experimental cancer drug during a critical period of cancer development.

"Brain cancers recruit the resources they need from the environment ...

Researchers world-wide are focused on clearing the toxic mutant Huntingtin protein that leads to neuronal cell death and systemic dysfunction in Huntington's disease (HD), a devastating, incurable, progressive neurodegenerative genetic disorder. Scientists in the Buck Institute's Ellerby lab have found that the targeting the protein called FK506-binding protein 51 or FKBP51 promotes the clearing of those toxic proteins via autophagy, a natural process whereby cells recycle damaged proteins and mitochondria and use them for nutrition.

Publishing in Autophagy , researchers showed that FKBP51 promotes autophagy through a new mechanism that could avoid worrisome side ...

Despite a name straight from a Tarantino movie, natural killer (NK) cells are your allies when it comes to fighting infections and cancer. If T cells are like a team of specialist doctors in an emergency room, NK cells are the paramedics: They arrive first on the scene and perform damage control until reinforcements arrive.

Part of our innate immune system, which dispatches these first responders, NK cells are primed from birth to recognize and respond to danger. Learning what fuels NK cells is an active area of research in immunology, with important clinical implications.

"There's a lot of interest right now ...

Army scientists working as part of an international consortium have developed and tested an antibody-based therapy to treat Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), which is carried by ticks and kills up to 60 percent of those infected. Their results are published online today in the journal Cell.

Using blood samples donated by disease survivors, the study's authors characterized the human immune response to natural CCHFV infection. They were able to identify several potent neutralizing antibodies that target the viral glycoprotein--a component of the virus that plays a key role ...

AMES, Iowa - An unexpected discovery by an Iowa State University researcher suggests that the first humans may have arrived in North America more than 30,000 years ago - nearly 20,000 years earlier than originally thought.

Andrew Somerville, an assistant professor of anthropology in world languages and cultures, says he and his colleagues made the discovery while studying the origins of agriculture in the Tehuacan Valley in Mexico. As part of that work, they wanted to establish a date for the earliest human occupation of the Coxcatlan Cave in the valley, so they obtained radiocarbon dates for several rabbit and deer bones that were collected from the cave in the 1960s as part of the Tehuacan Archaeological-Botanical Project. The dates for the bones suddenly ...

Key takeaways

The surgical simulator can realistically simulate multiple trauma scenarios at once, compared with traditional simulators that can only simulate one or a limited number of conditions.

Trauma team members who tested the simulator preferred it for its realism, physiologic responses, and feedback.

The benefits of this innovative simulator may be able to extend to other surgical procedures and settings.

CHICAGO (June 1, 2021): Simulators have long been used for training surgeons and surgical teams, but traditional simulator platforms typically have a built-in limitation: they often simulate one or a limited ...

University of South Florida researchers recently developed a novel approach to mitigating electromigration in nanoscale electronic interconnects that are ubiquitous in state-of-the-art integrated circuits. This was achieved by coating copper metal interconnects with hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), an atomically-thin insulating two-dimensional (2D) material that shares a similar structure as the "wonder material" graphene.

Electromigration is the phenomenon in which an electrical current passing through a conductor causes the atomic-scale erosion of the material, eventually resulting in device failure. Conventional semiconductor technology addresses this challenge by using a barrier or liner material, but this takes up precious space on the wafer that could otherwise be used to pack in ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- In 1916 and 1917, a musician and book dealer named Giovanni Concina sold three ornately decorated seventeenth-century songbooks to a library in Venice, Italy. Now, more than 100 years later, a musicologist at Penn State has discovered that the manuscripts are fakes, meticulously crafted to appear old but actually fabricated just prior to their sale to the library. The manuscripts are rare among music forgeries in that the songs are authentic, but the books are counterfeit.

Uncovering deception was not what Marica Tacconi, professor of musicology and associate ...