(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- For birds and other wildlife, winter is a time of resource scarcity. Extreme winter weather events such as a polar vortex can push some species to the edge of survival. Yet winter tends to get short shrift in climate change research, according to UW-Madison forest and wildlife ecology Professor Ben Zuckerberg.

"When we think about the impact of climate change, winter tends to be overlooked as a time of year that could have significant ecological and biological implications," says Zuckerberg. "It makes me, and my colleagues, think quite deeply about the impacts of these extreme events during this time when species are particularly vulnerable."

Zuckerberg, along with Jeremy Cohen, a former UW-Madison postdoctoral researcher now at the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change, and Daniel Fink of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, set out to learn how extreme winter cold and heat affected 41 common bird species in eastern North America. Their work, recently published in Ecography, found that individual bird species respond differently to these weather events, and extreme winter heat may lead to longer-term changes in bird populations.

The researchers analyzed extensive data submitted through eBird, a global citizen science initiative where bird watchers contribute checklists of birds observed at a specific location, date and time. They homed in on data occurring before and after a four-day-long polar vortex in January 2014 and a December 2015 heat wave. These two events were the coldest and warmest stretches observed in a decade, and each affected an area of about 2 million square kilometers in the midwestern and northeastern U.S. and Canada. The researchers also analyzed temperature and land cover data.

That's a lot of data. Twenty years ago, working with this amount of diverse data would not have been possible. However, recent advances in environmental data science have enabled ecologists to work at scales that reflect the vast regions and species affected by climate change.

With colleagues at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cohen and Zuckerberg used machine learning, an advanced computing technique used to gain insights from large data sets, to predict the abundance and occurrence of bird species starting 10 days before the onset of each extreme weather event, until 30 days after the event. They compared the data to identical time periods in 14 recent winters.

During the polar vortex, bird abundance -- the number of individual birds of a species observed in the study area -- decreased five-to-10 days following the event and returned to previous levels 20 days afterward, ruling out mortality as the reason for the decline. However, the prevalence of species across an entire region, or occurrence, was relatively stable. This result surprised the researchers, as local abundance and regional occurrence are usually closely linked.

"This data suggests some birds may have abandoned the area, moved south, and came back," says Cohen. "Alternatively, some birds could have laid low because of the stress caused by the cold, and then returned to earlier activity levels."

The data following the winter heat wave was even more surprising. Across most bird species, abundance and occurrence increased, and this trend persisted for 30 days following this extreme weather event. This may have been due to short-distance migrants moving into the area, and staying there, in response to warm weather.

"I was not expecting this impact of the winter heat wave effect," says Zuckerberg. "What I found to be most intriguing was the lasting and dramatic response."

Over the past 30 to 40 years, bird species have slowly moved northward. Ecologists believe this decades-long process is a response to climate change. However, Zuckerberg says that winter heat waves could speed up this geographic movement, and without time to gradually adapt, some birds may be more vulnerable to extreme heat or cold in new areas.

At the species level, Zuckerberg and Cohen found that warm-adapted and small bodied birds were more sensitive to both extreme heat and cold. Cold-adapted species were far more resilient.

The researchers also observed species-level differences related to habitat requirements. Waterbird species occurred more often after the polar vortex and less often after the winter heat wave -- the opposite of what was observed, on average, for other species. According to Cohen, open water bodies would have frozen during the polar vortex, perhaps causing species that overwinter at high latitudes to head south and seek more favorable habitat in the study area.

To help birds and other wildlife cope with extreme winter weather, wildlife managers can create sheltered habitats and other pockets of refuge. Continuous monitoring of bird activity and weather variability can help conservationists and policymakers predict which species will be most vulnerable to climate change over the next decade.

The confluence of environmental data science and citizen science is making this kind of prediction possible. As Zuckerberg puts it, "The amount of data we are getting through public participation in science has opened up new areas of exploration at a time that, frankly, we really need it, because climate change is such a big problem."

INFORMATION:

This study was funded in part by The Leon Levy Foundation, The Wolf Creek Foundation, NASA (80NSSC19K0180), the National Science Foundation (DBI-1939187; CCF-1522054; and computing support from CNS-1059284), and the UW-Madison Data Science Initiative.

--Cris Carusi, cecarusi@wisc.edu

Contact: Ben Zuckerberg, bzuckerberg@wisc.edu; Jeremy Cohen, jcohen39@wisc.edu

DOWNLOAD PHOTOS: https://uwmadison.box.com/v/winter-birds-climate

Using a piece of magnet, researchers have designed a simple system that can control the movement of a small puddle of water, even when it's upside down. The new liquid manipulation strategy, described in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science on June 3, can have a wide range of applications including cleaning hard-to-reach environments or delivering small objects.

Previous attempts to control the movement of fluids often relied on special platforms. For example, on a surface that has one section more hydrophobic than another, water will spontaneously ...

Anyone that's ever interacted with a dog knows that they often have an amazing capacity to interact with people. Now researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 3 have found that this ability is present in dogs from a very young age and doesn't require much, if any, prior experience or training. But, some of them start off better at it than others based on their genetics.

"We show that puppies will reciprocate human social gaze and successfully use information given by a human in a social context from a very young age and prior to extensive experience with humans," said Emily E. Bray of the University of Arizona, Tucson. "For example, even before puppies have left their littermates to live ...

Whales are largely protected from direct catch, but many populations' numbers still remain far below what they once were. A study published in the journal Current Biology on June 3 suggests that, in addition to smaller population sizes, those whales that survive are struggling. As evidence, they find that right whales living in the North Atlantic today are significantly shorter than those born 30 to 40 years ago.

"On average, a whale born today is expected to reach a total length about a meter shorter than a whale born in 1980," said Joshua Stewart of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in La Jolla, CA. That represents an average decline in length of about 7%. "But that's just the average--there are also some extreme cases where young whales are several ...

Patients who, perhaps unbeknownst to their health care providers, are in need of genetic testing for rare undiagnosed diseases can be identified en masse based on routine information in electronic health records (EHRs), a research team reported today in the journal Nature Medicine.

Findings from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center study suggest that, among the patients of any sizeable health care system, there are hundreds or thousands with undiagnosed rare diseases of the sort where a genetic test could lead to a diagnosis.

"Patients with rare genetic diseases often face ...

What The Study Did: Changes in pregnancy and birth rates before and after COVID-19 lockdown measures were estimated using electronic medical records.

Authors: Molly J. Stout, M.D., of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11621)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed this link to provide your readers free access ...

Quantum computers with their promises of creating new materials and solving intractable mathematical problems are a dream of many physicists. Now, they are slowly approaching viable realizations in many laboratories all over the world. But there are still enormous challenges to master. A central one is the construction of stable quantum bits - the fundamental unit of quantum computation called qubit for short - that can be networked together.

In a study published in Nature Materials and led by Daniel Jirovec from the Katsaros group at IST Austria in close collaboration with researchers from the L-NESS Inter-university Centre in Como, Italy, scientists now have created a new and promising candidate system for reliable qubits.

Spinning Absence

The researchers created the qubit using the ...

Dogs may have earned the title "man's best friend" because of how good they are at interacting with people. Those social skills may be present shortly after birth rather than learned, a new study by University of Arizona researchers suggests.

Published today in the journal Current Biology, the study also finds that genetics may help explain why some dogs perform better than others on social tasks such as following pointing gestures.

"There was evidence that these sorts of social skills were present in adulthood, but here we find evidence that puppies - sort of like humans - are biologically prepared to interact in these social ways," said lead study author Emily Bray, a postdoctoral research associate in the UArizona School of Anthropology in the College of Social and Behavioral ...

(Toronto, June 3, 2021) -- The impact of deploying Artificial Intelligence (AI) for radiation cancer therapy in a real-world clinical setting has been tested by Princess Margaret researchers in a unique study involving physicians and their patients.

A team of researchers directly compared physician evaluations of radiation treatments generated by an AI machine learning (ML) algorithm to conventional radiation treatments generated by humans.

They found that in the majority of the 100 patients studied, treatments generated using ML were deemed to be clinically acceptable for patient treatments by physicians.

Overall, 89% of ML-generated treatments were considered clinically acceptable for treatments, ...

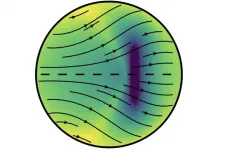

For reasons unknown, Earth's solid-iron inner core is growing faster on one side than the other, and it has been ever since it started to freeze out from molten iron more than half a billion years ago, according to a new study by seismologists at the University of California, Berkeley.

The faster growth under Indonesia's Banda Sea hasn't left the core lopsided. Gravity evenly distributes the new growth -- iron crystals that form as the molten iron cools -- to maintain a spherical inner core that grows in radius by an average of 1 millimeter per year.

But the enhanced growth on one side suggests that something in Earth's outer core or mantle under Indonesia is removing heat from the inner core at a faster rate than on the opposite side, under Brazil. Quicker cooling on one side would ...

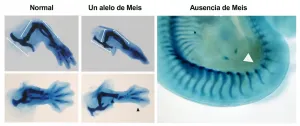

Scientists at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), working in partnership with researchers at the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) in Canada, have identified Meis transcription factors as essential biomolecules for the formation and antero-posterior patterning of the limbs during embryonic development.

In the study, published in Nature Communications, the research team carried out an in-depth characterization of the Meis family of transcription factors. Genetic deletion of all four family members showed that these proteins are essential for the formation of the limbs during embryonic development. "An embryo that develops in the absence of Meis does not ...