(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. - New research from MSU shows that an infant's gut microbiome could contain clues to help monitor and support healthy neurological development

Why do some babies react to perceived danger more than others? According to new research from Michigan State University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, part of the answer may be found in a surprising place: an infant's digestive system.

The human digestive system is home to a vast community of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. The MSU-UNC research team discovered that the gut microbiome was different in infants with strong fear responses and infants with milder reactions.

These fear responses -- how someone reacts to a scary situation -- in early life can be indicators of future mental health. And there is growing evidence tying neurological well-being to the microbiome in the gut.

The new findings suggest that the gut microbiome could one day provide researchers and physicians with a new tool to monitor and support healthy neurological development.

"This early developmental period is a time of tremendous opportunity for promoting healthy brain development," said MSU's Rebecca Knickmeyer, leader of the new study published June 2 in the journal Nature Communications. "The microbiome is an exciting new target that can be potentially used for that."

Studies of this connection and its role in fear response in animals led Knickmeyer, an associate professor in the College of Human Medicine's Department of Pediatrics and Human Development, and her team to look for something similar in humans. And studying how humans, especially young children, handle fear is important because it can help forecast mental health in some cases.

"Fear reactions are a normal part of child development. Children should be aware of threats in their environment and be ready to respond to them" said Knickmeyer, who also works in MSU's Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, or IQ. "But if they can't dampen that response when they're safe, they may be at heightened risk to develop anxiety and depression later on in life."

On the other end of the response spectrum, children with exceptionally muted fear responses may go on to develop callous, unemotional traits associated with antisocial behavior, Knickmeyer said.

To determine whether the gut microbiome was connected to fear response in humans, Knickmeyer and her co-workers designed a pilot study with about 30 infants. The researchers selected the cohort carefully to keep as many factors impacting the gut microbiome as consistent as possible. For example, all of the children were breastfed and none was on antibiotics.

The researchers then characterized the children's microbiome by analyzing stool samples and assessed a child's fear response using a simple test: observing how a child reacted to someone entering the room while wearing a Halloween mask.

"We really wanted the experience to be enjoyable for both the kids and their parents. The parents were there the whole time and they could jump in whenever they wanted," Knickmeyer said. "These are really the kinds of experiences infants would have in their everyday lives."

Compiling all the data, the researchers saw significant associations between specific features of the gut microbiome and the strength of infant fear responses.

For example, children with uneven microbiomes at 1 month of age were more fearful at 1 year of age. Uneven microbiomes are dominated by a small set of bacteria, whereas even microbiomes are more balanced.

The researchers also discovered that the content of the microbial community at 1 year of age related to fear responses. Compared with less fearful children, infants with heightened responses had more of some types of bacteria and less of others.

The team, however, did not observe a connection between the children's gut microbiome and how the children reacted to strangers who weren't wearing masks. Knickmeyer said this is likely due to the different parts of the brain involved with processing potentially frightening situations.

"With strangers, there is a social element. So children may have a social wariness, but they don't see strangers as immediate threats," Knickmeyer said. "When children see a mask, they don't see it as social. It goes into that quick-and-dirty assessment part of the brain."

As part of the study, the team also imaged the children's brains using MRI technology. They found that the content of the microbial community at 1 year was associated with the size of the amygdala, which is part of the brain involved in making quick decisions about potential threats.

Connecting the dots suggests that the microbiome may influence how the amygdala develops and operates. That's one of many interesting possibilities uncovered by this new study, which the team is currently working to replicate. Knickmeyer is also preparing to start up new lines of inquiry with new collaborations at IQ, asking new questions that she's excited to answer.

"We have a great opportunity to support neurological health early on," she said. "Our long-term goal is that we'll learn what we can do to foster healthy growth and development."

INFORMATION:

Note for media: Please include a link to the research article in your online coverage: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-23281-y

EAST LANSING, Mich. - It can be easy to forget that the human skin is an organ. It's also the largest one and it's exposed, charged with keeping our inner biology safe from the perils of the outside world.

But Michigan State University's Sangbum Park is someone who never takes skin or its biological functions for granted. He's studying skin at the cellular level to better understand it and help us support it when it's fighting injury, infection or disease.

In the latest installment of that effort, Park, who works in IQ -- MSU's Institute for Quantitative Health Science & Engineering -- has helped reveal how the skin's immune ...

Toronto -- Math continues to be a powerful force against COVID-19.

Its latest contribution is a sophisticated algorithm, using municipal wastewater systems, for determining key locations in the detection and tracing of COVID-19 back to its human source, which may be a newly infected person or a hot spot of infected people. Timing is key, say the researchers who created the algorithm, especially when COVID-19 is getting better at transmitting itself, thanks to emerging variants.

"Being quick is what we want because in the meantime, a newly-infected person can infect others," said Oded Berman, a professor of operations management and statistics at the University of Toronto's Rotman School of Management.

This latest ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A study by researchers at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center has found that cancer patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who received care at home via remote patient monitoring were significantly less likely to require hospitalization for their illness, compared to cancer patients with COVID-19 who did not participate in the program. Results of the study were presented Friday, June 4, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting and published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

"For our study, we evaluated 224 Mayo Clinic patients with cancer who were found to have COVID-19 through standardized screening prior to receiving cancer treatment, or due to symptoms or close exposure," says Tufia Haddad, ...

While previous research early in the pandemic suggested that the vitamin D cuts the risk of contracting COVID-19, a new study from McGill University finds there is no genetic evidence that the vitamin works as a protective measure against the coronavirus.

"Vitamin D supplementation as a public health measure to improve outcomes is not supported by this study. Most importantly, our results suggest that investment in other therapeutic or preventative avenues should be prioritized for COVID-19 randomized clinical trials," say the authors.

To assess the relationship between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 ...

Effector and killer T cells are types of immune cells. Their job is to attack pathogens and cancers. These cells can also go after normal cells causing autoimmune diseases. But, if harnessed properly, they can destroy cancer cells that resist treatment.

Scientists at St. Jude wanted to understand how these T cells are controlled. They looked at enhancers, sequences of DNA that when bound to certain proteins determine how genes are turned on or off.

The scientists found that enhancers of a gene named Foxp3 work as a pair to keep effector and killer T cells in check. The enhancers working together is essential.

"These ...

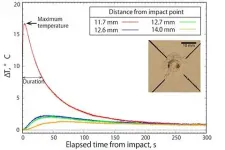

A research group from Kobe University has demonstrated that the heat generated by the impact of a small astronomical body could enable aqueous alteration (*1) and organic solid formation to occur on the surface of an asteroid. They achieved this by first conducting high-velocity impact cratering experiments using an asteroid-like target material and measuring the post-impact heat distribution around the resulting crater. From these results, they then established a rule-of-thumb for maximum temperature and the duration of the heating, and developed a heat ...

The melodic and diverse songs of birds frequently inspire pop songs and poems, and have been for centuries, all the way back to Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" or "The Nightingale" by H.C. Andersen.

Despite our fascination with birdsong, we are only beginning to figure out how this complicated behavior is being produced and which extraordinary specializations enabled songbirds to develop the diverse sound scape we can listen to every morning.

Songbirds produce their beautiful songs using a special vocal organ unique to birds, the syrinx. It is surrounded by muscles that contract with superfast speed, two orders of magnitude faster than e.g. human leg muscles.

"We found that songbirds have incredible fine control of their song, including frequency ...

Philadelphia, June 4, 2021--ADHD medications may lower suicide risk in children with hyperactivity, oppositional defiance and other behavioral disorders, according to new research from the Lifespan Brain Institute (LiBI) of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the University of Pennsylvania. The findings, published today in JAMA Network Open, address a significant knowledge gap in childhood suicide risk and could inform suicide prevention strategies at a time when suicide among children is on the rise.

"This study is an important step in the much-needed effort of childhood suicide prevention, ...

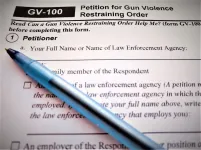

What The Study Did: This survey study in California assesses what the public knows about extreme risk protection orders and if people are willing to use them to prevent firearm-related harm, both in general and when a family member is at risk, and if not, why not. The orders temporarily suspend firearm and ammunition access by individuals a judge has deemed to be at substantial risk of harming themselves or others.

Authors: Nicole Kravitz-Wirtz, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of California Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0975)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please ...

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- Extreme risk protection orders, also known as END ...