(Press-News.org) Tiny algae in Earth's oceans and lakes take in sunlight and carbon dioxide and turn them into sugars that sustain the rest of the aquatic food web, gobbling up about as much carbon as all the world's trees and plants combined.

New research shows a crucial piece has been missing from the conventional explanation for what happens between this first "fixing" of CO2 into phytoplankton and its eventual release to the atmosphere or descent to depths where it no longer contributes to global warming. The missing piece? Fungus.

"Basically, carbon moves up the food chain in aquatic environments differently than we commonly think it does," said Anne Dekas, an assistant professor of Earth system science at Stanford University. Dekas is the senior author of a paper published June 1 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that quantifies how much carbon goes into parasitic fungi that attack microalgae.

Underwater merry-go-round

Researchers until now have predicted that most carbon fixed into colonies of hard-shelled, single-celled algae known as diatoms then funnels directly into bacteria - or dissolves like tea in the surrounding water, where it's largely taken up by other bacteria. Conventional thinking assumes carbon escapes from this microbial loop mainly through larger organisms that graze on the bacteria or diatoms, or through the CO2 that returns to the atmosphere as the microbes breathe.

This journey is important in the context of climate change. "For carbon sequestration to occur, carbon from CO2 needs to go up the food chain into big enough pieces of biomass that it can sink down into the bottom of the ocean," Dekas said. "That's how it's really removed from the atmosphere. If it just cycles for long periods in the surface of the ocean, it can be released back to the air as CO2."

It turns out fungus creates an underappreciated express lane for carbon, "shunting" as much as 20 percent of the carbon fixed by diatoms out of the microbial loop and into the fungal parasite. "Instead of going through this merry-go-round, where the carbon could eventually go back to the atmosphere, you have a more direct route to the higher levels in the food web," Dekas said.

The findings also have implications for industrial and recreational settings that deal with harmful algal blooms. "In aquaculture, in order to keep the primary crop, like fish, healthy, fungicides might be added to the water," Dekas said. That will prevent fungal infection of the fish, but it may also eliminate a natural check on algal blooms that cost the industry some $8 billion per year. "Until we understand the dynamics between these organisms, we need to be pretty careful about the management policies we're using."

Microbial interactions

The authors based their estimates on experiments with populations of chytrid fungi called Rhizophydiales and their host, a type of freshwater algae or diatom named Asterionella formosa. Coauthors in Germany worked to isolate these microbes, as well as bacteria found in and around their cells, from water collected from Lake Stechlin, about 60 miles north of Berlin.

"Isolating one microorganism from nature and growing it in the laboratory is difficult, but isolating and maintaining two microorganisms as a pathosystem, in which one kills the other, is a true challenge," said lead author Isabell Klawonn, who worked on the research as a postdoctoral scholar in Dekas' lab at Stanford. "Only a few model systems are therefore available to research such parasitic interactions."

Scientists surmised as early as the 1940s that parasites played an important role in controlling the abundance of phytoplankton, and they observed epidemics of chytrid fungus infecting Asterionella blooms in lake water. Technological advances have made it possible to pick apart these invisible worlds in fine and measurable detail - and begin to see their influence in a much bigger picture.

"We're realizing as a community that it's not just the capabilities of an individual microorganism that's important for understanding what happens in the environment. It's how these microorganisms interact," Dekas said.

The authors measured and analyzed interactions within the Lake Stechlin pathosystem using genomic sequencing; a fluorescence microscopy technique that involves attaching fluorescent dye to RNA within microbial cells; and a highly specialized instrument at Stanford - one of only a few dozen in the world - called NanoSIMS, which creates nanoscale maps of the isotopes of elements that are present in materials in vanishingly small amounts. Dekas said, "To get these single-cell measurements to show how photosynthetic carbon is flowing between specific cells, from the diatom to the fungus to the associated bacteria, it's the only way to do it."

The exact amount of carbon diverted to fungus from the microbial merry-go-round may differ in other environments. But the discovery that it can be as high as 20 percent in even one setting is significant, Dekas said. "If you're changing this system by more than a few percent in any direction, it can have dramatic implications for biogeochemical cycling. It makes a big difference for our climate."

INFORMATION:

Stanford coauthors include Alma E. Parada and Nestor Arandia-Gorostidi, postdoctoral research fellows in the Department of Earth System Science at the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). Additional coauthors are affiliated with Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, the Swedish Museum of Natural History and Potsdam University. Klawonn is now affiliated with Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research.

The research was supported by the German Academic Exchange Service, the Simons Foundation and the German Research Foundation.

Though it might seem inanimate, the soil under our feet is very much alive. It's filled with countless microorganisms actively breaking down organic matter, like fallen leaves and plants, and performing a host of other functions that maintain the natural balance of carbon and nutrients stored in the ground beneath us.

"Soil is mostly microorganisms, both alive and dead," says END ...

Like all metals, silver, copper, and gold are conductors. Electrons flow across them, carrying heat and electricity. While gold is a good conductor under any conditions, some materials have the property of behaving like metal conductors only if temperatures are high enough; at low temperatures, they act like insulators and do not do a good job of carrying electricity. In other words, these unusual materials go from acting like a chunk of gold to acting like a piece of wood as temperatures are lowered. Physicists have developed theories to explain this so-called metal-insulator transition, but the mechanisms behind the transitions are not ...

There's a lot of interest right now in how different microbiomes--like the one made up of all the bacteria in our guts--could be harnessed to boost human health and cure disease. But Daniel Segrè has set his sights on a much more ambitious vision for how the microbiome could be manipulated for good: "To help sustain our planet, not just our own health."

Segrè, director of the END ...

A new drug reduced tumor size in patients who have lung cancer patients with a specific, disease-causing change in the gene KRAS, a study found.

The results of the CODEBREAK 100 phase 2 clinical trial were presented June 4, 2021, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine. The efficacy and safety of the drug sotorasib, developed by Amgen Inc., was tested in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a specific change, or mutation, in the DNA code for KRAS.

The KRAS mutant protein targeted in the study was p.G12C, in which a glycine building ...

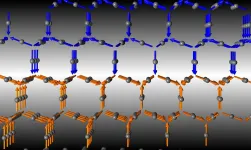

Washington, DC--A team led by Carnegie's Thomas Shiell and Timothy Strobel developed a new method for synthesizing a novel crystalline form of silicon with a hexagonal structure that could potentially be used to create next-generation electronic and energy devices with enhanced properties that exceed those of the "normal" cubic form of silicon used today.

Their work is published in Physical Review Letters.

Silicon plays an outsized role in human life. It is the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust. When mixed with other elements, it is essential for many construction and infrastructure projects. And in pure elemental form, it ...

A study of more than 1,000 demographically representative participants found that about 22 percent of Americans self-identify as anti-vaxxers, and tend to embrace the label as a form of social identity.

According to the study by researchers including Texas A&M University School of Public Health assistant professor Timothy Callaghan, 8 percent of this group "always" self-identify this way, with 14 percent "sometimes" identifying as part of the anti-vaccine movement. The results were published in the journal Politics, Groups, and Identities.

"We found these results both surprising and concerning," Callaghan said. "The fact that 22 percent of Americans at least sometimes identify as anti-vaxxers was much higher than expected and demonstrates ...

Most Americans should get screened for colorectal cancer beginning at age 45 instead of age 50, according to new recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which includes UVA Health's Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH. This recommendation applies to Americans without symptoms who do not have a history of colorectal polyps or a personal or family health history of genetic disorders that increase the risk of colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the third-leading cause of cancer death in America, according to the Task Force, and an increasing number of cases are being diagnosed in younger Americans. The Task Force notes that colorectal cancer diagnoses among Americans ages 40 to 49 increased by almost 15% from 2000-02 to 2014-16. Black ...

While previous research early in the pandemic suggested that vitamin D cuts the risk of contracting COVID-19, a new study from McGill University finds there is no genetic evidence that the vitamin works as a protective measure against the coronavirus.

"Vitamin D supplementation as a public health measure to improve outcomes is not supported by this study. Most importantly, our results suggest that investment in other therapeutic or preventative avenues should be prioritized for COVID-19 randomized clinical trials," say the authors.

To assess the relationship between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 ...

Tuberculosis (TB) is a deadly infection that occurs in every part of the world. The standard treatment for TB, a six-month multidrug regimen, has not changed in more than 40 years. Patients can find it difficult to complete the lengthy regimen, making it more likely that treatment resistance will develop.

A research team led by a Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) investigator reports in the May 6 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine that a four-month treatment regimen using rifapentine is effective for treating TB. Shortening the treatment duration is an important step toward increased patient adherence.

In 2019 alone, 1.4 ...

As meat-eating continues to increase around the world, food scientists are focusing on ways to create healthier, better-tasting and more sustainable plant-based protein products that mimic meat, fish, milk, cheese and eggs.

It's no simple task, says renowned food scientist David Julian McClements, University of Massachusetts Amherst Distinguished Professor and lead author of a paper in the new Nature journal, Science of Food, that explores the topic.

"With Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods and other products coming on the market, there's a huge interest in plant-based foods for ...